Mussolini: The Untold Story

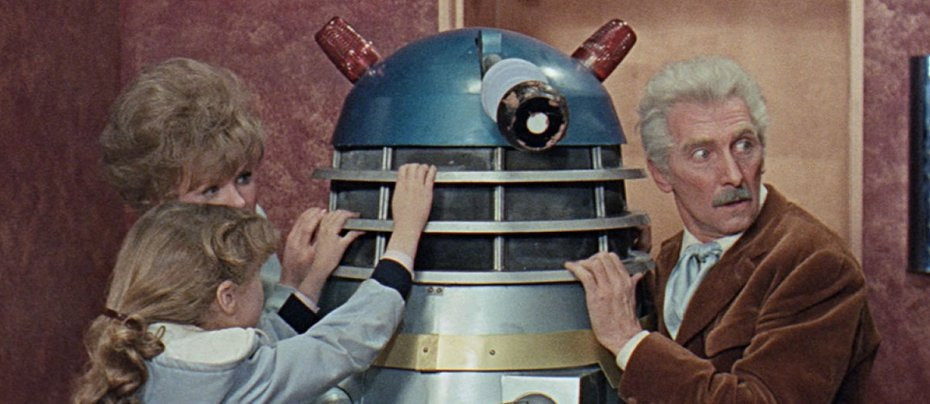

1985 - United StatesOne of the greatest film actors of his generation, (George C. Scott’s) Mussolini is one of his best roles

Mussolini: The Untold Story review by John Winterson Richards

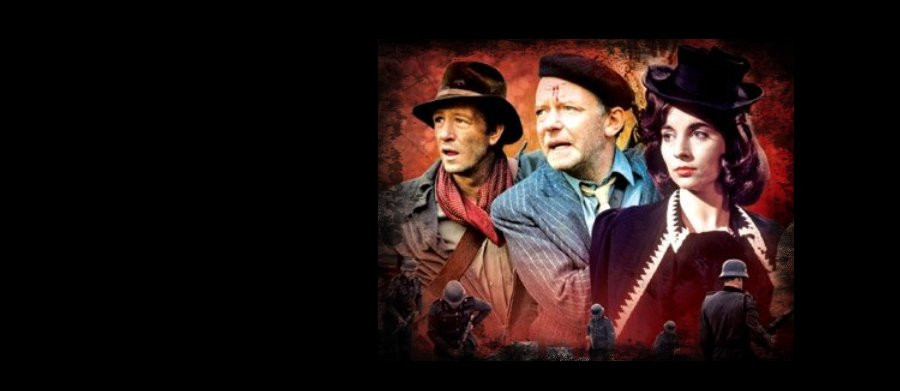

A rise in electoral support for Italian neofascism in the early Eighties was the background to two 1985 television dramatisations of the later years of Benito Mussolini: Bob Hoskins played the title role in Mussolini and I and George C Scott in Mussolini: The Untold Story.

Mussolini is a difficult protagonist for a "miniseries." He presents a dramatic dilemma. Should he be played as Buffoon, Villain, or Tragic Hero?

There is historical warrant for all three approaches. The contrast between his bombastic speeches and his pathetic performance in World War Two is the very essence of comedy - pompous man falls down. At the same time, on a more serious level, his active collaboration with Hitler in the murder of Italian Jews is enough on its own to justify his humiliating final public appearance, hanging from that garage in Milan (even if one does feel sorry for his mistress, Claretta Petacci, who did not deserve the same treatment).

The notion that he can also be viewed as a heroic figure, in the sense of the leading character in an opera, a great man destroyed by his own flaws, rather than a good man, is more controversial - and even the most sympathetic version of events demands a lot of qualifications and reservations - but it cannot be denied that his story is compelling.

In Act One a handsome young Socialist revolutionary who moves in the same circles as Lenin abandons Socialism out of patriotism and enlists to fight for his country in the Great War. Honourably discharged after being wounded, he seeks a third way between Socialism and Capitalism. Amid the Post-War turmoil, he rises within an extraordinarily short period of time to become Prime Minister at 39. He ends the turmoil and establishes order for twenty years. He modernises his country and literally makes the trains run on time - more or less. He heals a longstanding rift between the secular state and the Roman Catholic Church. He is a force for peace in Europe. He is admired across the political spectrum abroad. Then in Act Three, power corrupts, as it always does, and he falls more and more under the influence of a truly evil man, trying at first to compete with him but eventually becoming his puppet.

It has been airbrushed out of history, because it is now too embarrassing, how widely admired Mussolini was in the late Twenties and early Thirties. He was seen all over the world as the symbol of a technocratic future. Hitler was himself little more than a Mussolini "fan boy" at that point and even more respectable figures like Franklin Roosevelt tried to emulate some of his policies. If Mussolini used gangster tactics against his opponents, it has to be said that some of his opponents used the same methods. If Mussolini was brutal in building a Colonial Empire, the same charge can be laid against all the other Powers, including the United States. While his regime was openly totalitarian, at least it avoided Soviet-style mass executions and internment until its final years. The systematic persecution of the Jews was also a product of those last years, even if it is an exaggeration to suggest, as some have, that he was not Antisemitic himself. None of this excuses the wicked deeds for which he is responsible, but, like any historical figure, he has the right to be judged in his historical context.

The veteran scriptwriter Stirling Silliphant (In the Heat of the Night) had the integrity and the self confidence to try to be fair even to Mussolini. As a result, Mussolini: The Untold Story contains elements of all three possible Mussolinis: Buffoon, Villain, and Tragic Hero. This is only right, because any portrait would be incomplete without all three perspectives, and one wonders if it would be allowed these days, even from a writer of his distinction.

However, Silliphant seems to have been frightened by the abrupt transformation between the early Mussolini and the Mussolini of the War years. Perhaps in the interests of making the character seem more consistent, he portrays the younger Mussolini as nastier than he was and the older Mussolini as more agreeable. So the younger Mussolini is shown raping a journalist and gloating over photographs of executed rebels - not only fictional but contrary to what we know of the man. At the same time, no mention is made of his later collaboration with the Shoah. So he is accused of doing what he did not do and let off lightly for what he actually did.

Another weakness is that the story begins on the day Mussolini becomes Prime Minister of Italy, missing out the crucial "First Act" that is necessary to explain who and what Mussolini was, and how and why he became that. Reference is frequently made to his formative experiences in the dialogue, especially when he is reminiscing with his wife, but the motto of good scriptwriting is always "Show, Don't Tell."

Of course that late start was necessary to accommodate the star of the piece, George C Scott, who was at the time of filming actually close to the age Mussolini was when he ceased to be Prime Minister after twenty years in power. It was therefore something of a stretch to have him play Mussolini at 39 when he first assumed office and to have him play even younger would obviously have been out of the question.

Yet Scott's presence makes all these compromises worthwhile. One of the greatest film actors of his generation, Mussolini is one of his best roles. It helps that he bears a fairly strong physical resemblance to 'Il Duce' in his later years. More importantly, as he proved in his most famous role as General George S Patton, he was the master of the swaggering virility of the self conscious leader figure. One understands why this is a man other men followed, even when one can see his weaknesses not far from the surface.

Scott also gets to show a more human side to Mussolini - when he is humbled in defeat and in the more intimate moments with his family. Mussolini really does seem to have been that great cliché of the Italian family man, a poor husband but a doting father, and retained the affection and devotion of those closest to him even beyond the grave.

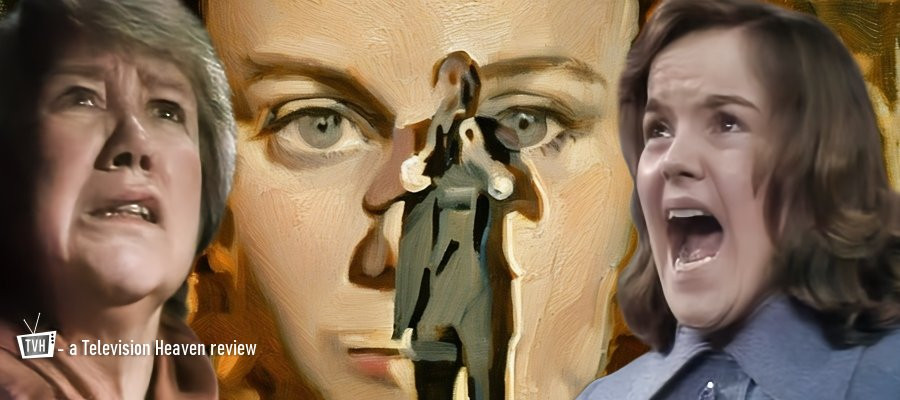

Lee Grant is the classic strong minded, down to Earth Italian "Mama" as his long suffering wife, Rachele. A peasant at heart, she is often the voice of reason in the script and one sees how the pair of them truly loved each other in spite of his numerous infidelities.

Virginia Madsen is luminous as the ill-fated Claretta - perhaps a bit too luminous: the evidence suggests that the real Claretta was not the brightest bulb in the box, but there is no doubt of the sincerity of her passionate obsession with Mussolini.

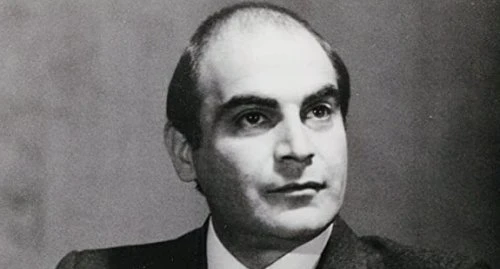

Raul Julia demonstrates he can excel in a straight role, and also reminds us what a great talent was lost too soon, as Mussolini's son in law, Count Ciano. He invests the character of the playboy politician with a poignancy the opportunistic original might not have deserved. Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio is appropriately feisty as his wife, very much her father's daughter, who nevertheless finds a more transcendent quality towards the end.

The odd pairing of Gabriel Byrne and a very young, pre-stardom Robert Downey Jr as Mussolini's two oldest sons by Rachele works surprisingly well. More perhaps could have been made of the fact that the elder, Vittorio, had a number of Jewish friends and seems to have resisted his father's Anti-Semitic policies, albeit passively.

David Suchet is totally convincing as the man who overthrew Mussolini. It helps that he looks a lot like his historical counterpart, as does Orson Welles collaborator George Coulouris as Marshal De Bono, another conspirator. The ubiquitous Vernon Dobtcheff is well cast Mussolini's loyal secretary Sebastiani, as is Philip Madoc as his Chief of Police Bocchini - despite apparently being badly and unnecessarily dubbed. Kenneth Colley is a suitably nervous King Vittorio Emmanuele and it is a pity he is not given more to do. Tony Vogel's brief appearance as a Fascist tough is enough to remind us of the tiger Mussolini was riding from beginning to end.

The "miniseries" does well to give us a real sense of grandeur on a television budget through a clever combination of stock footage and location work - in Italy and, it seems, also across the Adriatic, Yugoslavia apparently sometimes standing in for Italy. Colourised footage from the time helps with the crowd scenes, but occasionally this strikes a false note: at one point it is implied there is a huge crowd just waiting outside Mussolini's office for him to step out and address them at will. The alternative is a major speech being made before a small crowd of extras, which also spoils the effect.

The big action set piece, Skorzeny's dramatic rescue mission on the Gran Sasso, is well handled and historically accurate - even if it misses the best part, the terrifying flight afterwards which put Mussolini in more danger than he was in before his rescue. The production is in general true to history: there are some changes for dramatic effect, but they do not alter the basic narrative.

There is a rousing score by Laurence Rosenthal, who did a lot of this sort of stuff around this time and deserves to be better known for it.

The ending does not pull its punches and is savagely true to fact. As a result, it has a powerful emotional impact - but what exactly those emotions might be depends on how one feels about Mussolini by this point. Thanks to Scott's humanizing performance, they might be more mixed than one expected at the start.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on June 1st, 2022. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.