The Secret Agent

1992 - United KingdomJoseph Conrad is most famous for his tales of adventure in exotic locations at a time when Imperialist Britons considered the whole world their playground. So his readers were perhaps a little disappointed by The Secret Agent, a claustrophobic study in misunderstanding and miscommunication set largely in the seedy end of London. It did not sell well.

Yet it has become something of a "cult" item. Those who like it often like it a lot. The "Unabomber," Ted Kaczynski, kept a copy with him in his notorious cabin in the woods and liked to identify himself with the character of "The Professor," a lonely, ruthless nihilist whose dreams of destruction extend even to himself.

However, one does not have to be a psychopath to appreciate its clever construction and its penetrating psychological insight. It is a good example of the literary craftsmanship that made Conrad a favourite among fashionable Post-War critics, shifting easily between concise but evocative descriptions of externals and the inner workings of the human mind.

This great strength of Conrad's has always made him a challenge to adapt. How does one put thought on a screen? It took all the brilliance of Sir Alfred Hitchcock to break it down to a succession of subtle details in 'Sabotage,' a very loose adaptation of 'The Secret Agent' and arguably the film that really cemented his reputation.

For a long time, no one dared compete. Then, in the 1990s, came two prestigious new versions in swift succession, both sticking much closer to the original novel. The first was a three-part television "miniseries" for the BBC starring David Suchet. The second was a full dress feature film with Bob Hoskins, who was another on whom the novel appears to have had a particular impact: the project seems to have been a personal passion and he acted as executive producer.

This is a review of the Suchet version, but it has been interesting to rewatch them together as part of the review process and compare the two. It is a good illustration of the superiority of a high quality television production over a cinematic release in terms of having the time to involve the viewer more completely in the story and its environment.

The novel is the squalid tragedy of Adolf Verloc, a man with a double life - or possibly a quintuple life. On the surface, he is a respectable married small business owner. Scratch that surface and he is not quite so respectable: his marriage is mainly one of mutual convenience and his business is selling pornography. Scratch a little more and even that is revealed as a cover for his real life, for he is an active member of a terrorist network - even if its members now spend more time talking than doing any actual terrorism.

That actually suits Verloc, because dig a little deeper and you find his main source of income is as a secret agent employed by a foreign Embassy - not named in the novel but by implication Russian - to spy on his fellow terrorists. Even that is not the whole story, because a combination of blackmail and help with his illegal business activities has turned him into a top informant for Chief Inspector Heat of the Metropolitan Police.

As a result, Verloc himself gets a little confused about where his loyalties lie. He still likes to think of himself as an Anarchist, but his wife and business, supposedly just a cover for his terrorist activities, seem to fill a higher priority in his thoughts. He hates his new handler at the Embassy, but retains an odd respect for his former controller, and even takes a perverse pride in his work for him. For all his revolutionary fervour, and his superficial bourgeois respectability, he retains a proletarian cringe towards aristocratic authority.

There are hints that his past services as a secret agent were indeed very effective - and that he was well connected, even respected, in Anarchist circles - but now he is held in contempt by all. His competing obligations make him very much a man on his own. He cannot trust anyone, not even his own wife. It is his failure to confide in her that completes his downfall.

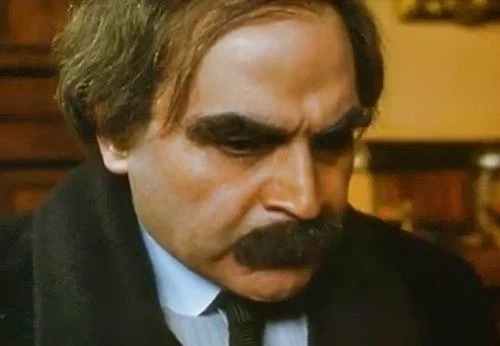

Verloc is a beautifully drawn character - and one of several parts David Suchet seems to have been born to play. Suchet is the main reason to watch the television version and he is simply magnificent. His complete identification with the eponymous Poirot is perhaps too successful in that it tends to obscure what a versatile and talented actor he is. He is arguably the most intelligent British actor of his generation. It remains a mystery worthy of Hercule's little grey cells why, at the time of writing, he remains unknighted when several less distinguished actors have received the Accolade.

He has made something of a speciality of outwardly insensitive characters, like Poirot and Verloc, who are in fact hiding deep vulnerabilities. Where Bob Hoskins in the film gives us a Hoskins-type dominant-male Verloc, Suchet's is a proud man forced by circumstances to hide his pride. We find an unexpected sympathy for him as we see the mistakes he is making while he remains oblivious of them.

Almost as good is Patrick Malahide as the unnamed Assistant Commissioner of Police to whom Chief Inspector Heat reports. His effectiveness as villains or authority figures - or villainous authority figures - has led Malahide to be cast in many such roles, so that, like Suchet, his broader skills are not as appreciated as they ought to be.

He therefore makes the most of a rare opportunity to play a more complex - and likeable - character. The Assistant Commissioner is professionally confident, having been promoted to London after a successful career in the Colonies, but socially insecure. He has married above himself and is afraid of offending his wife's social circle. This is personified by a politically naïve Duchess who enjoys the frisson of having a leading Anarchist in her salon. She is charming and helpful to the Assistant Commissioner, but, as played by the great Janet Suzman, firm in her sense of aristocratic entitlement. She makes it clear that she is not a woman to cross and her liberalism does not extend to tolerating those who question it.

This aspect of the story is expanded from the novel, possibly as an excuse to put in some pretty costume drama as an antidote to the drabness of Verloc's existence. If so, the overall plot does not suffer. On the contrary, we are given two strong storylines, Verloc's and the Assistant Commissioner's, with very different endings, making an important point about the contrast between the fates of the powerful and the powerless.

Cheryl Campbell, a reliable actress who deserves to be better known, strikes an authentic note as Mrs Verloc, as does the ever watchable Warren Clarke as Chief Inspector Heat. If Jim Broadbent's rather nervy Heat in the film sticks more the mind, Clarke gives the more credible portrait of a mid-rank professional policeman, astute, perceptive, and firmly in control of his own little part of the world, if rather out of his depth in the political world in which his superior, the Assistant Commissioner, proves himself an accomplished player.

That political world is represented by the Home Secretary, a superb cameo by a perfectly cast Stratford Johns. It is a well observed sketch of a senior politician, exhausted by a long, unrelated debate in Parliament, but still sharp and keen to be seen to be in command.

Peter Capaldi also makes a strong impression at a transitional point in his career as the new First Secretary of the Embassy, a clever young man who wants to show how clever he is. Like all the other officials in the story, he is keen to show he is charge, so he sweeps his predecessor's successful arrangements aside and risks a valuable asset in a scheme he has dreamt up to make a big impression. This it does, but not in the way he intends. In the end he is revealed as the bungling amateur Verloc believes him to be - but by then it is too late for Verloc: once again, the powerless pay the price for the mistakes of the powerful. The First Secretary's character arc within the story becomes a morality tale in its own right.

Although this is a review of the television series, not the film, it is worth noting that the former can offer nothing like the latter's most memorable performance - by Robin Williams, cast very much against type, as "The Professor." One believes completely that this insignificant looking loser will one day suddenly - or rather at twenty seconds notice - blow himself up and take everyone around him with him. It is a chilling reminder that no one is as dangerous as the man who really does not care whether he lives or dies.

Lacking Williams' star power, the television production rather downplays the role, as it does that of another of the Anarchists, a low rent ladies man who maintains himself by seducing vulnerable women out of their savings - made overly likeable by Gerard Depardieu in the film.

Otherwise, the television version is better on almost every point. It is closer to the novel and, by opening up the story a little, it actually appears to have better production values. The score by the late Barrington Pheloung, best known for the theme from Inspector Morse, is in keeping with the period, if sometimes a little too intrusive. Both the Bob Hoskins film and the David Suchet television series are worth a look, but, if you have to choose, watch the David Suchet version - above all for David Suchet.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on November 20th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.