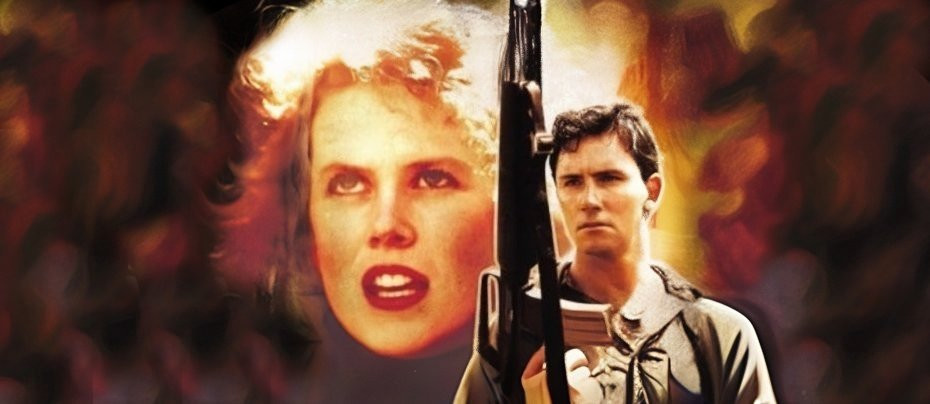

Medici the Magnificent

2019 - Italy UkAlthough both are sometimes lumped together as a single show, called simply Medici, because they are produced by most of the same people, Medici the Magnificent is really a separate sequel to the sumptuous Medici: Masters of Florence. Apart from a few flashbacks to the latter, with cameos from a couple of its actors, the cast is different and so is the story, even if both are still part of the epic family history of the 15th Century bankers, patrons of the arts, and 'de facto' rulers of Florence.

A generation has passed between the end of Medici: Masters of Florence and the beginning of Medici the Magnificent. For the last few years, Cosimo's inadequate son, Piero, now played by Julian Sands, has been leading the House and Bank of the Medici, having become an even more inadequate patriarch. This is historically unfair: Piero, known as "the Gouty" - his limp was not due to a late injury as suggested by the plot - had always been sickly and had not been expected to succeed his father, but he rose to the occasion manfully and did a good job stabilising the Bank's precarious finances after Cosimo's high spending.

The script, however, calls for Piero to be ineffective so that the main protagonist, his masterful son, Lorenzo the Younger, known to history as "the Magnificent" - hence the title - can shunt him aside. In fact Piero's death forced Lorenzo to take over at a much younger age than anyone wanted. What the script gets right is that Lorenzo turned out to be a natural leader, not only of the Bank but of the Republic of Florence and of the cultural movement that was later labelled the Renaissance. Although the historical Lorenzo was not as handsome as Daniel Sharman, who plays him, he was in other respects just as impressive as he is portrayed - a champion jouster, a passionate sponsor of the new art and the revival of Greek learning in Italy that drove the Renaissance, the unofficial ruler of Florence at the height of her greatness, and an outstanding diplomat who was relatively successful in maintaining peace between the various Italian States until his death in 1492. The fact that everything fell apart so quickly without him is perhaps the greatest proof of his political acumen. Nevertheless, his son and nephew still became Popes, and his cultural legacy endured and is influential in the West to this day.

At the same time, Medici the Magnificent shows the price of this. Like his grandfather, Cosimo, Lorenzo was a big spender, especially on his political and artistic projects. Unlike Cosimo, Lorenzo rather neglected the Bank, the foundation of his family's wealth and therefore of its power. There are some passing references in the dialogue, but it was Sovereign Debt that really sank the Medici Bank. Indeed, it is a good example of the failure to learn from history that people who lend money to governments usually come to regret it because they ultimately find it is impossible to get it back when there is a dispute or a default. In the case of the Medici, they made the mistakes of lending money to Charles the Bold of Burgundy in his struggles against Louis XI of France and to the Yorkists in the Wars of the Roses. Charles was defeated and defaulted, while there was obviously no chance of the victorious Henry Tudor paying the debts his Yorkist enemies had contracted.

One of the missed opportunities of 'Medici' is that it never really engages with this international aspect of the Medici's financial operations. It prefers to focus on Italy for the obvious commercial reason that it was made for RAI, the Italian state broadcaster.

The greatest strength of Medici the Magnificent is therefore its location work in Italy. This, combined with first class cinematography and some clever CGI, makes it simply one of the best looking shows ever made. Centuries are stripped away to provide a credible evocation of the 'Quattrocento,' and whole armies march across the gorgeous landscapes without us seeing the joins. If some locations are anachronistic - there is quite a bit of 16th Century architecture on display - and some shots become rather familiar over the course of a season, they do nothing to undermine the overall effect. The colourful costumes, set dressing, and recreations of famous art works complete the overwhelming visual impact. It is worth watching just for that.

The drama itself is also compelling. One has a good sense of how the Medici, for all their wealth and power, indeed because of their wealth and power, were under constant pressure. The Pazzi Conspiracy and the events leading up to it are handled particularly well, so that its relatively minor inaccuracies are forgivable. One sees the confusion that often surrounds great moments of history and how they often turn on trivial things. Almost inevitably, everything after that is rather anticlimactic, but there are some exciting individual episodes. The conclusion, which has an increasingly desperate Lorenzo making uncharacteristically bad decisions in the knowledge that he has little time left, is powerful, despite being heavily fictionalised.

Sharman is an appropriately self confident leading man, even if he is not the historical Lorenzo. Sean Bean, the only really big name in the cast, goes Full Villain as Lorenzo's rival for power in Florence, Jacopo de' Pazzi. Sebastian de Souza (The Great) is closer to what history gives us as Lorenzo's friend, the painter Botticelli. Johnny Harris is a fine addition as Lorenzo's quietly efficient and slightly sinister fixer. Ray Stevenson's imposing physical presence makes him an appropriately intimidating King Ferrante of Naples. Sam Mackay makes a strong impression as an authentic soldier of fortune of the time, and Francesco Montanari is a convincing Savonarola. The decision to replace Raoul Bova with John Lynch as Pope Sixtus IV seems strange: both are fine actors who do good things with the role, but they are so different that it is like watching two completely separate Popes.

The realities of the modern market dictate that women are portrayed as being more influential than they usually were in 15th Century Italy. Since no one does powerful women better than Sarah Parish, the suggestion that Lorenzo's mother actually ran the Bank seems less unlikely with her in the role than many historians would allow. By contrast, the formidable Caterina Sforza Riario, a rare example for the time and place of a woman who was an important public figure, and who later commanded troops in person, is rather underplayed as a battered wife. Stunning Alessandra Mastronardi has a satisfying story arc as Lorenzo's alleged (probably Platonic) mistress and Synnove Karlsen is likeable as his wife (and probable true love).

Executive Producer Frank Spotnitz and his writing team have clearly done their research. There are a lot of "Easter eggs" and in-jokes for those who know the period immediately after Lorenzo's death. A lot of subsequently important names are checked. At one point Pope Sixtus tells Botticelli of the glory that will come with painting the 'Cappella Magna' (Great Chapel) - because it has not yet been named the Sistine Chapel after Sixtus. It is surprising that the Borgia are never mentioned, even in the episode relating to the 1484 Conclave, in which Lorenzo is shown as a major player and Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia really was. Perhaps the producers should be commended for resisting the temptation to put the two big family names of the Renaissance head to head (they were in fact allies): it might have been too much of an overload.

That the writers have obviously done their reading makes it all the more frustrating that they get some significant facts so badly wrong. Although the Medici, like most nobles of the time, fathered illegitimate children almost as a matter of course, the notion that Lorenzo and his brother would both cuckold politically powerful nobles is absurd. God, Family, and Money were always the top priorities for the Medici - not necessarily in that order. Their hedonistic love of pleasure was always restrained by their religion and by a practical calculation of their own interests.

The script has Lorenzo prose on about making Florence a "true Republic," implying he supports a more democratic system. In fact it was the democratic faction that rose against the Medici after Lorenzo's death. Lorenzo himself courted popularity with the mob and used it to advance his political agenda but that agenda was conservative: he had a vested interest in maintaining a system that enabled him to control the Republic without ever holding high office himself.

Lorenzo is shown as going completely Michael Corleone in seeking revenge after the Pazzi Conspiracy when the truth is that he was amazingly moderate under the circumstances, even to the extent of trying to restrain public outrage. There is no evidence that his religious faith was in any way damaged by the Conspiracy. It is one of the ironies of history that he was an early sponsor of the radical preacher Savonarola, who did indeed attend him on his death bed. The balance of the evidence suggests they were on good terms. Savonarola became politically powerful only in the vacuum left by Lorenzo's passing, and the famous "Bonfire of the Vanities" - to which the very religious Botticelli may have contributed some of his own work - took place five years after Lorenzo's death. It could not have happened in his lifetime.

It is above all completely wrong to suggest that Lorenzo's political judgement deserted him in his final days. While it may provide the pretext for some exciting drama, it goes not only against history but against the consistency of his dramatic character as established in previous episodes. This is important because it misses the real point of the story: the tragedy of Lorenzo is that he was a force for peace and civilisation in a very violent period. One can only imagine how different history might have been if he had lived another thirty years.

Spotnitz returned to the Renaissance to produce Leonardo for RAI and Amazon. Like 'Medici,' it is distinguished by its wonderful visual style, but it cannot be considered the third part of a trilogy. Apart from anything else, the Leonardo of Leonardo is a very different character from the Leonardo who makes a couple of guest appearances in Medici the Magnificent. If Spotnitz were to conclude a 'Medici' trilogy it would be good if he could take up the story immediately after Lorenzo's death when the leadership of Italy effectively passed to Cardinal Borgia, who became Pope Alexander VI a few months later. There is a great story to tell there, and despite several attempts, notably in 1981 and 2011, it has never been told satisfactorily. It would be interesting to see Spotnitz' take on it in all its visual splendour.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on November 15th, 2021. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.