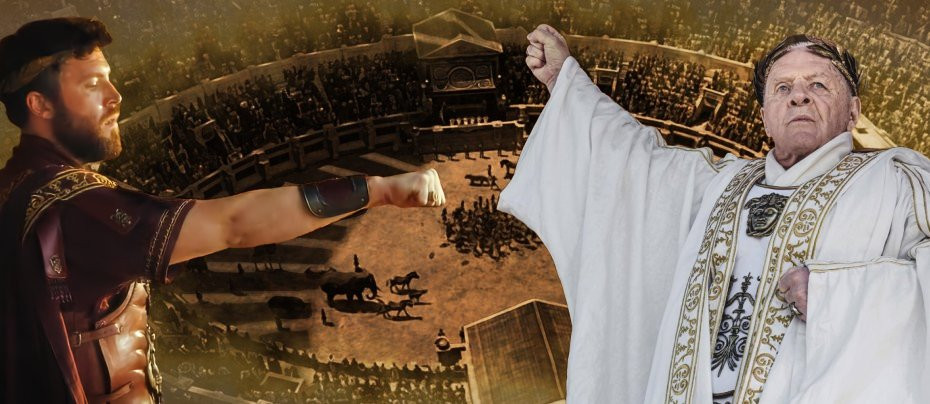

The Two Popes

2019 - Italy UkOne of the consequences of the vast increase in the number of video channels and platforms in recent years has been an erosion of barriers between genres and even between media. Anything goes now. It all comes out on the same screen in the end, and possibly a very small screen at that.

In particular, the internet has accelerated the greying of the boundaries between cinema and television production which began decades ago. There used to be a definite snobbery in cinema about television, all the more intense for being the snobbery of a parvenu. A proper "above the line" film star who took a regular role on a television drama or sitcom was seen as giving up on competing in the top division. Conversely it was very difficult for even the very wealthy stars of successful television shows to build film careers afterwards: their very success counted against them because it was assumed, not without reason, that audiences would associate them too much with their television roles. Cameos either side of the line were fine, but as far as principal roles were concerned you were on one side or the other.

While some old attitudes still remain, the line itself is now gone. The most prestigious names in cinema, like Robert De Niro, Julia Roberts, and Sir Anthony Hopkins have not thought it beneath them to accept the leading roles in episodic series. Dwayne Johnson was recently the highest paid film actor in the world and at the same time the leading man in a television series, Ballers.

Meanwhile, the bigger platforms have adopted the wise strategy of investing directly in high quality, high prestige productions - previously the exclusive domain of cinema - in order to stand out in a crowded market. Netflix recently made the particularly daring decision to compete with cinema on its own home ground. The traditional model is for a feature film to be sold to television for broadcast after its theatrical run, the television rights being the jam on top of the bread and butter. Netflix turned this model on its head: their films would make their money back principally by attracting viewers to their subscriber platform, the income from a short theatrical run being the jam. The real purpose of the theatrical run was to give the films the prestige and publicity of being full dress cinematic releases, making them eligible for major film Award nominations, including the Oscars.

This strategy proved more successful than even the most optimistic Netflix executive might have imagined. Oscar nominations poured in, much to the chagrin of the official film industry which grumbled about the eligibility of "television movies" with only a token theatrical release. The quality of the Netflix productions, their excellence purely as cinema, soon silenced such complaints. One of their first efforts in this regard, Alfonso Cuaron's Roma received multiple nominations and missed winning "Best Picture" only very narrowly: that it did not is considered by many one of the Great Oscar Robberies.

Netflix followed it up the following year with two more massive prestige projects that attracted multiple nominations: The Irishman, in effect the fourth film in Martin Scorsese's informal Mafia trilogy starring De Niro, and The Two Popes.

Although cinematic in style and scope, The Two Popes is actually in structure very much an actor's piece. Indeed, it started life as a play. To draw attention away from this, Netflix invested in some spectacular location work, and a meticulously crafted reproduction of the Sistine Chapel at the Cinecitta Studios in Rome. Yet the whole thing still comes down to two old men talking

...which turns out to be as dramatic as any action adventure.

The two men are meant to be the then Pope, Benedict XVI, and Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio - surely no spoiler alert is required because the title rather gives it away - the man destined to be Benedict's successor as Pope, Francis I. The words "meant to be" apply because most of the script, by Anthony McCarten, the original playwright, is explicitly a speculation. This is a legitimate device but dangerous. As drama it asks some valid questions that one would like to think the actual men at least considered, but as history it is sometimes on dodgy ground.

The script has Bergoglio, plagued by guilt and self doubt as a result of the moral compromises he had to make in Argentina's "Dirty War," wanting to resign as Archbishop of Buenos Aires. He travels to Rome to submit his resignation to the Pope. Since he had been the Pope's main rival at the Conclave that had elected Benedict, he expects a cold reception and Benedict is indeed very distant at first.

Only gradually does it become apparent that Benedict himself is also plagued with guilt and self doubt, in his case due to the mismanagement of child abuse allegations, and in his turn wants to resign, or rather abdicate, as Pope. This shocks Bergoglio: while retirement has become standard practice for Bishops in recent decades, it was not always so and the convention that the Pope served for life was actually strengthened over the centuries. There were precedents but they were associated with low points in the long history of the Papacy.

Benedict's desire to resign is particularly surprising, as is his confiding in Bergoglio, because Benedict is viewed as ultraconservative and Bergoglio is relatively "liberal," at least in Vatican terms. Where Bergoglio is sympathetic to "worker priests" reaching out to the marginalised, Benedict is portrayed as the ultimate insider. Before his election he was Prefect of the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, the organisation formerly known as the Holy Office or the Inquisition. In that role his staunch defence of orthodoxy and tradition earned him the affectionate nickname "God's Rottweiler."

Despite their differences, the pair begin to talk frankly. Bergoglio's surprise grows when Benedict reveals that he considers him his likely successor (in reality, both were well aware of the fact that Bergoglio was generally seen as 'papabile'). Benedict admits his failings in a formal Confession to Bergoglio - which, true to the seal of the Confessional, the viewer does not hear, so that the exact nature of those failings is kept cleverly ambiguous. Bergoglio is also able to move on from his past. Bonding over their awareness of their own imperfections, the two men reach a mutual understanding, and eventually, it is implied, establish a sort of friendship.

That is it. There are a lot of flashbacks into Bergoglio's past, and some suitably cinematic camera work, especially at the Villa Farnese and the Palace of Caserta, but the scenes that stick in the mind are the intimate conversations between Benedict and Bergoglio.

This is because they are played by two truly great actors. As it happens, both are Welsh, but such is their authority that the viewer accepts without hesitation that Sir Anthony Hopkins is the German Benedict and Sir Jonathan Pryce is the Argentine Bergoglio. They adopt the national characteristics of their respective roles without ostentation or apparent self consciousness. Indeed, although Benedict and Francis are both very famous living men, it is difficult, having seen The Two Popes, to think of either of them without thinking of Hopkins and Pryce.

Hopkins is widely acknowledged as arguably the greatest actor of his generation full stop. If he sometimes turns up for the cheque, then so did Olivier and Gielgud. What counts is when he brings his A-game, and that is what he does in The Two Popes. His Benedict exudes power, even before his election as Pope when we see him working the room among the Cardinal electors. This is a man confident that he ought to be Pope and we can see that confidence convincing the Cardinals. That he is old and sometimes seems a little vague only shows how strong he really is because even in his weakness we sense that this man is in control. This makes it all the more poignant when he begins, very cautiously, to reveal his vulnerability.

Pryce also has a glorious curriculum vitae, even if he has not really had his fair share of the glittering prizes. He plays Bergoglio as a sensitive man trying to do the decent thing behind an official façade his circumstances force him to assume. There is an obvious parallel here with his most famous film role, as the conflicted bureaucrat in Brazil. At the same time his Bergoglio has a magnetism and a natural ability to engage with ordinary people that the scholarly Benedict lacks. It is a nice touch that Bergoglio seems unaware of this talent, but Benedict can see it in him and knows that he does not have it himself.

The fact that both actors can evoke such total identification with their characters poses an ethical problem. To what extent is it fair to promote images of living people and their relationship which may be totally inaccurate? The question is of particular importance where the people have public images which are of political significance? The Pope is the uncontested leader of the world's largest and most powerful organised religion. Its active members include the current President of the United States, as well as numerous other Heads of State and Government. It is a major provider of education, health and welfare services, community leadership, and cultural cohesion in many parts of the world. The public perception of the Papacy is therefore an issue of great importance, and not just to Roman Catholics.

A popular drama will be seen by far more people than books or long articles on its subject, and a good one will have a greater impact even on those who do read. So the biggest criticism of The Two Popes may be that it is simply too good - because it becomes so believable that it might encourage viewers to assume that what was written as speculation is actually true.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on September 22nd, 2021. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.