Leonardo

2021 - ItalyReview - JWR

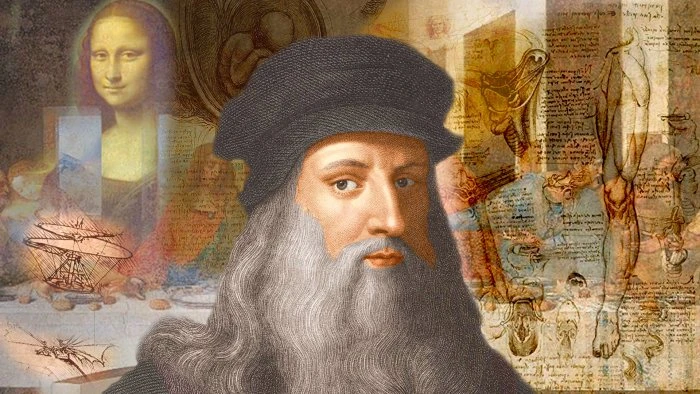

One of the handful of people, which also includes his great competitors Michelangelo and Raphael, who made such a mark on history that it is sufficient to refer to them by their Christian names alone, Leonardo da Vinci is endlessly fascinating. Painter, engineer, inventor, anatomist, and scientist before science was science, Leonardo has become the archetype of the Renaissance Man, both in the sense of an expert at a lot of different things and one who epitomises the Renaissance period. The essential difference between him and someone who merely has a lot of interests is how his restless mind brought originality and insight to everything he attempted or studied.

There is another side to the coin. This very restlessness, which drove him from one obsession to another, meant he was distracted very easily from his paid work. In his lifetime he developed a reputation for not completing his projects. This is why less than a dozen paintings reliably attributed solely to Leonardo, as opposed to his workshop, are with us today. His daring experiments often failed. Many of his famous inventions are impractical. His scientific speculations, limited by the information available to him at the time, were usually leaps of intuition: sometimes they turned out to be right; sometimes not.

Something similar can be said about Leonardo, the recent Amazon series that purports to be a dramatization of the life of the great polymath. Given its subject matter, it cannot be anything less than fascinating, and, like Leonardo, it combines many different skills and talents to brilliant effect, but, also like Leonardo, it tries to be several different things at once - a murder mystery, a domestic and psychological drama, a documentary on the artistic process, and a historical biography - and it succeeds in some better than others.

Now, in the name of full disclosure, you deserve to be made aware that, for reasons that should be clear should you read the biographical note below, your reviewer happens to know a little bit about Leonardo, and has strong opinions on some of the many controversies that surround him. The writers of Leonardo have differing opinions on some of these points, which is their right: how dull the world would be if we all thought the same.

However, there is one objective fact that the Leonardo writers get very badly wrong, and it taints what is otherwise a very enjoyable show. They portray the young Leonardo as what can only be described as a nerd who has difficulty communicating with people and deep psychological issues. From there he develops into the traditional lonely tortured artist.

Our sources tell us the complete opposite. In addition to a list of talents that would make anyone envious, Leonardo was blessed with the gift of charm. Well adjusted, an outstanding musician (of course), kind, generous, and fond of jokes, he was apparently very good company. No wonder almost everyone seems to have loved him - from his Royal and noble patrons, through fellow artists and intellectuals who became close friends, to devoted assistants who stayed with him for decades.

So it is odd that the Leonardo of Leonardo actually seems to have more in common with the historical Michelangelo Buonarroti, his great rival, fellow Florentine genius, and direct opposite in so many respects. Curiously, Michelangelo is portrayed in Leonardo as being very sociable. The real Michelangelo did indeed develop his own circle of friends and admirers, but even they seem to have accepted that his artistic temperament could sometimes make him difficult.

This inaccurate portrait of Leonardo rather undermines the historical biography aspect of the production. It makes for good drama but poor history. It is a pity because Leonardo goes to a lot of trouble to get a lot of the less important details absolutely right. This is hardly a surprise because it is the work of two literate writers with strong records in historical drama, Frank Spotnitz, who developed and demonstrated a good understanding of Renaissance Italy in the superb Medici: Masters of Florence, and Steve Thompson, who wrote Vienna Blood.

As is to be expected, the influence of Medici: Masters of Florence is all over Leonardo, not just in the writing. This is undoubtedly a good thing, but the two projects are equally frustrating in that the viewer who is lured into believing that he is watching truth, and usually is, may be misled when fact shades into fiction, first into speculation and then into falsehood.

To be fair, most of the fiction is well within the bounds of dramatic licence. One of the reasons Leonardo is so compelling is that he is a genuine man of mystery: there are huge gaps in the record and it is perfectly legitimate for a dramatist to use his imagination to try to fill them in. It is another thing altogether to be positively anti-historical, to suggest, for example, that Leonardo was a loner and that Cesare Borgia was simply a lunatic, as Leonardo implies.

Liberties are taken with the chronology. The events portrayed in Leonardo took place over almost four decades: Leonardo went from a teenaged apprentice to a celebrity artist in his fifties. Yet he does not seem to age that much, nor do any of the other characters. Again the historical biography takes second place to the domestic drama, which actually detracts from the drama in the end, because it is more powerful when the viewer can be assured that it is true.

The murder mystery element is at first a rather distracting framing device, but stick with it because it all comes together rather cleverly in the end.

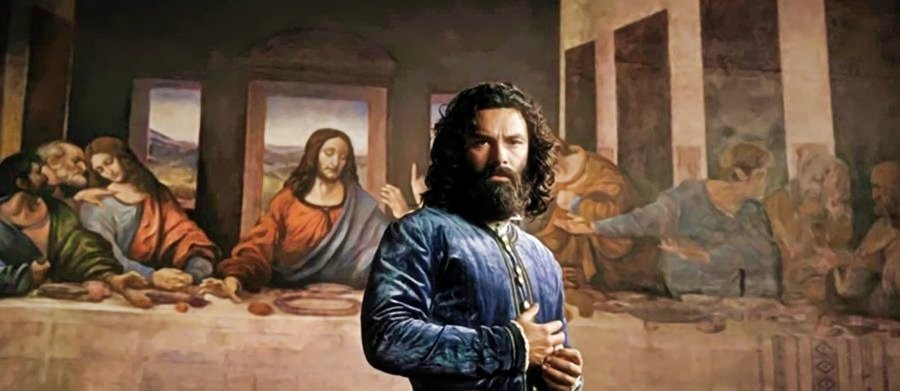

By far the best thing about Leonardo is its ambitious dramatization of the artistic process, both physical and mental. We get to see the authentic techniques of the period and we are also given some very well educated guesses about what Leonardo was thinking. Of course, we can never be certain of what goes on in someone else's head, let alone a mind like Leonardo's, but we are offered credible conjecture consistent with known facts. The script shows how Leonardo was so innovative without trying to hide his mistakes. Each of the eight episodes is centred on one of his major projects, the one on his fresco of 'The Last Supper' at Santa Maria delle Grazie being, perhaps inevitably, both the most illuminating and the most powerful.

The art and design departments take on a particular importance in this context, and they prove more than up to the challenge. It is certainly a huge advantage that the series was filmed in Italy, the Land of Artists, and the nation that produced Leonardo, Michelangelo, and the Renaissance was able to confirm that their tradition lives on there still.

As was apparently also the case for Medici: Masters of Florence, the participation of the Italian state broadcaster RAI seems to have been of particular benefit. Leonardo had access to some prime locations, and if some are anachronistic - the wonderful gardens of the Villa d'Este in Tivoli were constructed over forty years after Leonardo's death - who cares? They look stunning.

Most of the filming, however, took place on an unusually large specially commissioned set, augmented by some seamless CGI. The authentic period style lighting and unfussy ground level camera work give us the impression we are in the same rooms and walking the same streets as Leonardo. This is vital given that Leonardo's visual perception of his world is a major theme of the script.

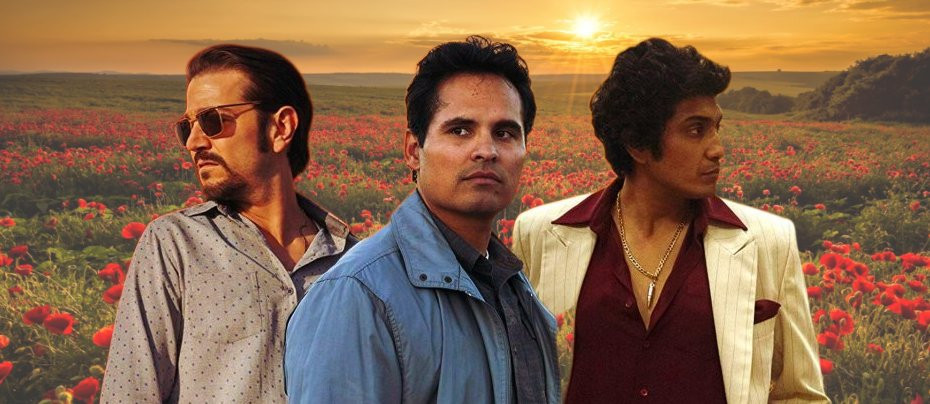

Aidan Turner in the title role does his best work in years. Having shown enormous potential as a leading man in Desperate Romantics' - as another artist, one very different from Leonardo, Dante Gabriel Rossetti - and Being Human, he achieved the fame he deserved as an amorous dwarf in The Hobbit trilogy and as the eponymous Poldark, but these roles did not really demand much of his considerable acting skills. Leonardo does. If his is not the historical Leonardo, that is not Turner's fault: he delivers what the script requires of him, which is a fine characterisation in its own right. Particularly impressive is the way he seems to mature emotionally, despite the fact that, physically, he always looks like a man in his thirties.

The supporting performances are of varying quality. At the top end of the scale, the always impressive Giancarlo Giannini is perfect as Leonardo's master and mentor, Verrocchio, on the surface a severe authority figure who gradually comes to appreciate how Leonardo shares his passion for artistic truth. James D'Arcy is a convincing Renaissance statesman, both urbane and ruthless, even if he is not the Ludovico Sforza of history (for which he cannot be blamed: the Regent, then Duke, of Milan was nicknamed 'Il Moro,' meaning "the Moor," because of his dark complexion, which D'Arcy could only have attained with the sort of make-up associated with an old time white actor playing Othello - not an option these days).

Davide Iacopini is nicely Machiavellian as, er, Machiavelli, who really was hanging out with Cesare Borgia around the same as Leonardo. Robin Renucci brings a poignant dignity to the part of Leonardo's father, who is presented in the script as estranged and distant (in fact he seems to have been quite supportive of his illegitimate son in his career). Carlos Cuevas makes Leonardo's troublesome assistant Salai a lot more likeable than he probably was. Matilda De Angelis does well in the role of the only woman who really matters in Leonardo's life, despite being given little by history or by the script on which to build her character.

Yet if there are a lot of quibbles about that script, it is only because it is frustrating how it falls just short of greatness. Overall, Leonardo is still a classy bit of television, and it is welcome news that a second season has been ordered.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on May 10th, 2021. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.