Squid Game

2021 - South KoreaThe astonishing rise of South Korea as an economic power in the last seventy years since the Korean War is excelled only by its even more astonishing rise as a cultural superpower in the last ten years. 'Gangnam Style' introduced the world to "K-pop" and 'Parasite' became the first foreign language film to win the Oscar for Best Picture. Now 'Squid Game' has conquered television, becoming, at the time of writing, the most successful Netflix show to date.

One can see why. At its heart is a simple but brilliant concept. Around the time of the 2008 crash, with his career apparently going nowhere and seriously short of cash, writer-director Hwang Dong-hyuk asked himself honestly what exactly he might be willing to do for money at that point. His answer was influenced by the Japanese 'Battle Royale,' in which teenagers fight to the death on a television show. 'Battle Royale' started a genre of its own - which does not include the similarly themed 'Hunger Games,' written independently by the American novelist Suzanne Collins, who had not seen 'Battle Royale,' the film being considered too insensitive for a general release in the United States in the wake of the Columbine murders.

Hwang concluded, probably correctly, that there was no shortage of people desperate enough to risk their lives for a substantial sum. From there it would be easy to manipulate them into actually killing each other. This was considered too dark at the time and his idea did not find a backer. Soon afterwards his career began to take off after all. He subsequently made several successful feature films, including 'The Fortress,' a superior historical drama that manages to be both epic and subtle. So his 'Battle Royale' idea remained in a drawer, or the electronic equivalent, for ten years until Netflix started looking actively for more Korean sourced content.

Although 'Squid Game' was released with minimal publicity and has famously become a sleeper hit through word of mouth, or internet, someone obviously had enough confidence in the project from the start to put a lot of money into the production. There is quite a bit of location work and a huge crowd of extras - at least in the beginning.

Above all, the sets and costumes give the show a distinctive style, and this visual impact helps make it more accessible to international audiences. Influences appear to include 'The Prisoner,' M C Escher, Roger Corman's cheap and cheerful features, and Sir Ken Adam's villains' lairs in early Bond films. Like the Bond villains, the organisers of the festivities in ‘Squid Game’ also have a small private army, but their cleverly designed faceless uniforms makes them look like inhuman robots. There is a wonderful use of colour throughout.

The design of the venue for the six games or trials is all the more sinister for the constant references to childhood and children's games, a constant theme in the trials themselves. A giant doll is particularly frightening, and with good reason.

The six trials themselves are thought out very carefully. Success in different trials depends on different factors: self control, physical strength, intelligence, luck, the ability to understand others, and character, or perhaps lack of character, all turn out to be necessary for survival. The problem is that one does not know which skills will be required for each contest. For a long time, before their purpose as entertainment becomes clear, one wonders if this is not some extreme social psychology exercise like the Milgram Experiment or the Stanford Prison Experiment. Or are the participants being taught some elaborate moral lesson? No. As it turns out, they are just being killed for sport.

The gamesmasters are fanatical about rules. Strict fairness is their only morality. They have no interest in what happens beyond the scope of the letter of their agreement with the participants and the rules of the trials themselves. The participants soon realise that this means it may be possible to reduce the competition and increase their own share of the potential prize money by thinning the herd a little. So in addition to the dangers of the trials themselves the participants have to survive the dangers of the anarchy that prevails in the periods between them.

Although the trials are not formal social experiments, we and the characters still learn a great deal about human nature. Some show altruism. Others are selfish. Some are manipulative. Others are bullies. Some co-operate, and indeed even the selfish eventually see the need to form teams or gangs for the sake of their own survival. All reveal their true nature under pressure. Many find they are not who they thought they were, or who they appeared to be. While for a few this means they rise above what their past lives might have suggested, most begin to diminish before our eyes. The bad get worse and the good were never really that good. The most interesting characters go on a real rollercoaster: they seem to be growing in adversity, only to fail a crucial moral test, and the fascinating question becomes whether they can find enough in themselves to get back up again.

As in all great drama, the viewers find themselves putting themselves in the place of the participants and asking what they would do differently. Would they be more likely to survive? Would they be more ethical? The moral descent of the characters is presented so credibly that the honest viewer will begin to wonder if, like most of the characters, they would be revealed as someone less than the person they imagine their-self to be.

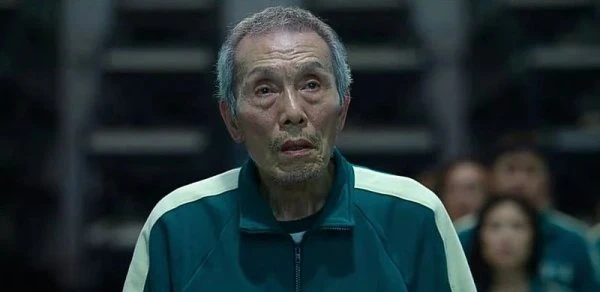

The characters themselves start out as archetypes. We have the total loser, the disgraced financier, the refugee from North Korea, the innocent immigrant, the career criminal, the streetwise chancer, and the old man with a brain tumour and nothing to lose. Yet all reveal hidden depth and some evolve in unexpected ways as the story progresses.

Lee Jung-jae plays a pathetic deadbeat Dad destined for a long, tortuous journey. Park Hae-soo is his old childhood friend, once the Golden Boy of their poor neighbourhood, who, as everyone keeps mentioning, went on to the prestigious Seoul National University (SNU) - which just happens to be Hwang's 'alma mater.' The distinguished Lee Byung-hun, who played the Minister inclined to peace in Hwang's earlier 'The Fortress,' plays a very different character here, the ruthless Front Man, known simply as "the Front Man," for the Host of the games.

However, the acting honours must be awarded to O Yeong-su as the old man whose memory of the games he played as a child proves to be a valuable asset, especially combined with the simple joy he takes in being able to play them again. One cannot help thinking that younger generations brought up on computer games would be at a major disadvantage.

Overall, the themes, plotting, tension, production values, and characterisation of 'Squid Game' justify its instant status as "must see" television. This is not to say it is perfect. On the contrary, it is a very uneven show. It must be seen for its great highs, but it also has its deep troughs.

It starts very slowly. The Lee Jung-jae character is initially so unsympathetic, stupid as well as selfish, that it is hard to keep watching. Stick with it. Everything changes when the first trial begins. There is a definite "This just got real" moment.

The fact that the game sequences are so compelling - they really would make a great "reality television" show - means that there is a distinct drop in attention in between. Subplots about a policeman running around the place and organ harvesting go precisely nowhere - so that even Hwang seems to have lost interest in them. Glimpses of the strictly regimented lives of the guards and of the cliched wealthy backers of the games detract from the fear, uncertainty, and claustrophobia of viewing everything from the participants' point of view. The attempts at social commentary are heavy handed. It is not bad, but one begins to wonder why all the fuss...

Then comes the sixth episode, 'Gganbu.'

In the history of television, there are moments that transcend the medium. One thinks of the departure of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Blake in 'M*A*S*H' or the final episode of 'Chernobyl' - and now 'Gganbu.' Everything that 'Squid Game' has been building up until then is delivered in a single sustained emotional barrage. The episode begins with two not entirely unpredictable plot twists, then thirty minutes of growing tension, and then ten minutes of unbearable poignancy. It is a masterpiece of writing, acting, and directing, not to mention set design and lighting. If it was an English language production, the Awards season would be a no contest.

How can one follow perfection? There lies the difficulty. 'Squid Game' peaks too early. Despite that, the seventh episode keeps up the pace, opening with another good plot twist and delivering another exciting game sequence. Alas, it is the last. The final game, the eponymous squid game, comes down to a dull fight between two men who are not very good at fighting. Yawn. Indeed, the last two episodes in general are both flat and disappointing, even detracting from the emotional impact of previous events with gratuitous plot twists.

If 'Squid Game' is therefore ultimately a let-down in the immediate context of what has gone before, it must be stressed that it is still worth watching, at least for the first seven episodes. It is that rare combination of exciting and thought provoking television. It says something important about us and about our time - not least that its popularity suggests that a mass audience would probably enjoy a real contest on these lines, if it was televised, as much as the evil wealthy backers do in the show.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on October 20th, 2021. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.