Ivanhoe (TV Movie)

1982 - Uk UsaBy John Winterson Richards

There is nothing new about the notion of the "reboot." There are some stories, especially in the action-adventure genre, that simply keep coming back because they are simply great stories with great characters.

The most obvious examples are two of the oldest and most successful literary franchises in history: Malory's King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, and the Child ballads of Robin Hood and his Merry Men. If he was around today, Alexandre Dumas pere would be copping a fortune in royalties for constant remakes of 'The Three Musketeers' - as well as the occasional 'Man in the Iron Mask,' 'Count of Monte Cristo,' and 'Corsican Brothers' - and doubtless still spending every penny of it. His pal Victor Hugo would be doing well out of 'Les Miserables,' while James Fenimore Cooper might resent Michael Mann for ruining his previously lucrative 'Last of the Mohicans' brand by making the definitive film version. As it is, the authors are not here to collect and all are conveniently out of copyright.

Sir Walter Scott's 'Ivanhoe' is in the same category. It was bred for success, incorporating elements of both King Arthur - knights errant and a King incognito - and Robin Hood, who makes an important guest appearance under the name of Locksley. However, far from exploiting them, Scott was reviving them: their enduring popularity to this day is due to his rediscovery of them.

It is perhaps difficult to convey just how big Scott was in his lifetime - and for much of the rest of the 19th Century. In terms of commercial success, the only comparison is with J K Rowling, except Scott was far more influential. He basically invented the modern historical novel, and later writers who these days are considered far more respectable acknowledged their debt to him. He was the world's first real "celebrity author," with literary tourists from all over the world flocking to Abbotsford, the Baronial-style mansion he built out of his earnings.

His prose style is of its time and has not aged well. His dialogue is often the subject of mockery. His plot construction is poor by modern standards: in some of his most famous novels, including 'Ivanhoe,' the hero is immobilised for much of the book.

Yet he remains very readable - and filmable - because of his skill at imagining completely different times and places, and populating them with memorable characters. This is especially true of 'Ivanhoe,' his most enduring and frequently adapted work.

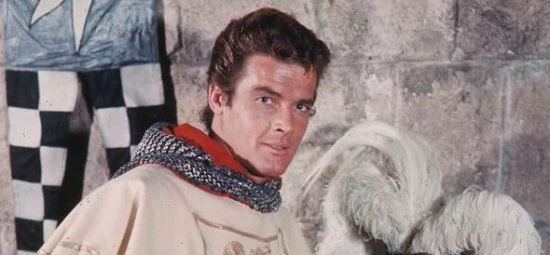

The best known version is the colourful 1952 Robert Taylor film, but there is also a new television adaptation every few years. Roger Moore first came to public attention as Ivanhoe in a cheerful serial in the late 1950s that had little in common with its source material. The BBC did a cheap but creditable children's version in 1970 and then a far more serious "miniseries" in 1997, complete with some very serious actors and an attempt at political context.

In between came this 1982 "television movie" for ITV and CBS which is notable for being positively cinematic in both its look and its overall production values.

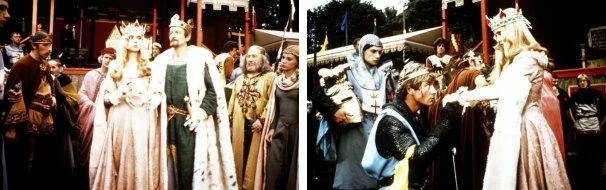

The first thing one notices about it is the colour and use of light. The deliberate use of bright colours is a lost art that ought to be revived. It looks particularly good in medieval epics, even where it is not wholly accurate. Immediately it references the splendid Robert Taylor version, and indeed the Technicolor grand-daddy of the whole genre, the Errol Flynn 'Adventures of Robin Hood,' as well as a small host of Saturday afternoon Robin Hood knock offs.

Much of the filming was done on location, with authentic castles and forests, and acres of green sward. Some effort seems to have been made to film only on sunny days - something that is very uncommon now thanks to tight shooting schedules and increased labour costs - so the skies are always blue. This adds a great deal to the mood of the piece. We are back in an idyllic Merry England, or possibly Merrie England, before those pesky social historians ruined it by going on about how unsanitary it all was.

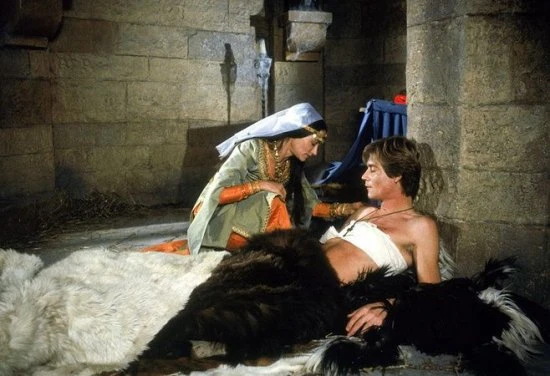

Someone seems to have thrown a lot of money at the project, not least in the casting, which is itself worthy of a full cinematic feature. Top of the list is a genuine film star, James Mason as the Jewish merchant Isaac of York, with Olivia Hussey as his daughter, Rebecca.

Anthony Andrews seems to have been cast in the title role simply because he was seen as being a name on the rise at that point: if so, it was a decision that did not help the actor or the production, because he looks out of place in it. If there is nothing wrong with his performance, neither does he bring anything to raise it above the restrictions Scott's plotting puts on it. A surprisingly passive character becomes more passive as others carry the action forward. The same is true of his lady love, Rowena, played by Lysette Anthony.

The rambunctious trio of villainous knights played with commitment by three actors near the start of very successful careers, Sam Neill, John Rhys-Davies, and Stuart Wilson, is far more engaging. There is a sparky interplay between them: like many ambitious young men, they are not sure themselves if they are friends or competitors. Incidentally, Neill saw Mason very much as a mentor, and it is interesting to compare their voice patterns in this and other projects.

Another coming man of the time, David Robb, plays it perfectly straight as Locksley, commendably resisting the temptation to self-satire inherent in the role. The always watchable Ronald Pickup is suitably sleazy as a Prince John in the fine tradition of Claude Rains.

Julian Glover is wholly credible as Richard the Lion Heart, a formidable warrior and natural leader of men with the total self-confidence that comes with being born into entitlement. Although he plays a benevolent role in these proceedings, as the historical Richard liked to do on occasion, one can easily imagine that this is the man who ordered the Massacre of Acre.

Michael Hordern and Michael Gothard - a great talent who was lost too soon - provide good comic relief as a couple of Saxon nobles, one as absurdly proud as the other is gluttonous, while George Innes is quite poignant as their own official comic relief, Wamba the jester.

The two big set pieces, the Tournament at Ashby and the Siege of Torquilstone, are suitably epic. Again, it is a marvel how much was done on a television budget. There was no stinting on the extras and costumes, and the fight arrangement and stunts are professional. People look as if they are really trying to kill each other. The Sam Neill character's escape from Torquilstone is particularly well done: one understands why no one wanted to get in the way of a medieval war horse.

If the third and final set piece, the Trial by Combat at the Preceptory, is a bit anticlimactic, that is partly the fault of the structure of the book. If anything, the film improves on the book by making the result depend more obviously on the ambiguity of the supposed villain.

Nevertheless, it is a tribute to the original novel that this adaptation, like most others, stays quite close to it. There are some attempts to make it more "modern" and "relevant" with speeches about tolerance and the like, with special reference to Antisemitism. Yet they are unnecessary, because Scott was actually well ahead of his time in this respect. He does not beat his readers over the head with a "message" but rather lets the casual contempt with which the Jewish characters are treated, even by other characters we are supposed to like, speak for itself.

The production has the courage to retain this, together with Scott's rather bleak ending. There is a jolly speech about Normans and Saxons becoming one people - a Scott invention - but no one, absolutely no one, suggests a similar reconciliation of Christians and Jews. There is no acknowledgment on the part of the Christians, other than Ivanhoe, that the Jews have behaved nobly or even that they have suffered unjustly. Nor do the Jews depart with a higher opinion of the Christians, other than Ivanhoe.

For the only conclusion they draw from these events is that it is safest to depart from Merrie England altogether. Given what history tells us happened to the Jews of England over the next century, it was a sensible decision from the point of view of their descendents. Not so sensible was their decision to depart to Spain of all places - but then no one expected the Spanish Inquisition.

For some reason, it has become something of a tradition for Swedish television to show this film annually around Christmas or the New Year. No one knows why. One would understand a great deal about the Swedes if one did.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on January 16th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.