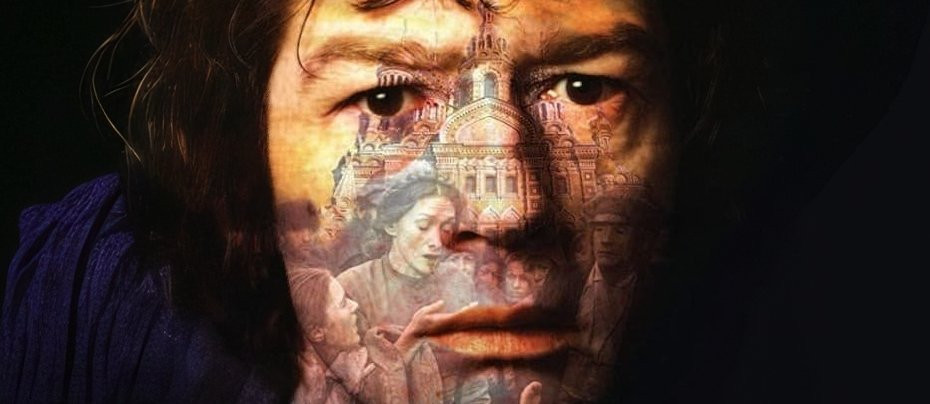

Crime and Punishment

1979 - United KingdomDirector Michael Darlow maintains the suspense with positively Hitchcockian levels of skill

Review by John Winterson Richards

The influential critic H L Mencken listed Fyodor Dostoevsky as the most boring writer of all time, which tells you all you need to know about influential critics. Dostoevsky is certainly a difficult read, but he yields great rewards to those who stick with him. Clinical psychologist Jordan Peterson describes him as the Master of the Psychological Novel in the same way that Tolstoy is the Master of the Sociological.

Peterson goes on the explain that while most authors write characters whose views differ from their own as "straw men," who can be knocked down easily by the author's own supposedly superior wisdom, Dostoevsky writes them as "iron men" who retain their internal credibility to the end. So while Dostoevsky was a political liberal his stories often lead to conservative conclusions, and although he was himself a thoughtful Christian his most memorable characters are unbelievers.

Such is Raskolnikov, a penniless law student with delusions of grandeur, in Dostoevsky's best known work, Crime and Punishment. Raskolnikov has imbibed the Nihilism fashionable among young self-consciously self-styled "intellectuals" in mid-19th Century St Petersburg. Rejecting God, and with Him all notions of conventional morality, he replaces Him with a young man's belief in the invincibility of his own will. He compares himself with Napoleon (as such people usually do, ignoring a great deal about the Corsican chancer's actual career) and Ivan the Terrible (a typically Russian touch). He comes across almost as a satire of the Nietzschean "superman," who claims his "will to power" is beyond Good and Evil, written decades before Nietzsche, who was a big Dostoevsky fan, invented the concept. Today he would probably be a "reddit atheist," but Raskolnikov wants to do more than write about his opinions. He decides to put his belief in his philosophy to the test by committing a horrific crime.

The irony is that Raskolnikov is not who he thinks he is - before, during, and, above all, after his criminal act. He is not what we would now diagnose as a psychopath. He is, on the contrary, a particularly sensitive young man, prone to impulsive acts of kindness and generosity. The fact that he has to persuade himself of the morality of his crime before committing it suggests he is not even the Nihilist he pretends to be: it is in practice very difficult to believe in nothing - because to believe in nothing is itself a belief and therefore belief in something.

Presenting these mainly internal philosophical and psychological conflicts within a Dostoevsky character externally in a drama is obviously a huge technical challenge to any adaptor. Despite this there have been a number of film and television adaptations of Crime and Punishment. One of the best is the three-part 1979 miniseries made by the BBC, who started with the wise decision of putting the script in the capable hands of Master Adaptor Jack Pulman, his laurels still fresh from his success with I, Claudius for them.

Indeed the project seems to have been intended as a prestigious follow up to I, Claudius, reuniting several members of the cast: John Hurt, who played Caligula, is a brilliant Raskolnikov, and Sian Phillips, who played Livia, appears here as another very proud lady, except with a completely different character in a completely different situation, while Christopher Biggins, who played Nero, has a guest scene as a physician.

No one does self-induced paranoia better than John Hurt - just look at his precocious breakthrough role in the Oscar winning A Man For All Seasons, especially the "Employ me" scene where his character reveals his desperation - so it is no surprise that he excels as Raskolnikov, a man who comes to be defined by his fears. His emaciated, slightly feverish appearance actually makes him a better Raskolnikov than the one presented in the novel, in which his good looks telegraph him too much as the tragic hero. Hurt's Raskolnikov tries to cover his obvious nervousness with a display of offended dignity, another Hurt specialty, which makes him look even more suspicious, a fact of which Raskolnikov himself seems wholly unaware but which is all too apparent to most of the other characters and to the viewer.

Timothy West, as the most courteous criminal investigator in history or literature, also departs slightly from the novel to good effect. At first he seems too avuncular, even buffoonish, to represent a serious threat to the overconfident Raskolnikov. The scene in which he reveals his true nature is a masterpiece, one of the greatest in West's distinguished career. An unexpected event saves Raskolnikov on that occasion but from that moment on we are in no doubt that we are watching a cat playing with a mouse he knows he is going to catch.

He is not the only member of the guest cast to be allowed to steal a scene even from Hurt on top form. Frank Middlemass, who was enjoying a late career Golden Age around this time, is incredibly moving as a literally hopeless drunk, a man who is objectively contemptible but still arouses the pity of Raskolnikov, and even the most hardened viewer (or reviewer) will understand why. His absolute hopelessness sums up the first part of the adaptation, in which it seems Raskolnikov's whole world consists almost entirely of people without hope.

Only later does it become apparent, perhaps a little too easily, that Raskolnikov despaired too soon: hope reappears, or perhaps should always have been there, but by then it is too late for Raskolnikov. A rather convenient friend, played by a well-cast David Troughton, turns up, and is both conveniently gullible and conveniently well connected - the investigator happens to be a cousin, and his wide circle of friends includes Biggins' physician and the investigator's clerk played by Malcolm Tierney (Lovejoy). Others who care for the ungrateful Raskolnikov include the warm-hearted maid in the house where he lodges played by Anne Orwin and his common sense sister played by Prunella Ransome. Anthony Bate is appropriately unsettling as a weary, wealthy libertine consumed by self-hatred who also turns out to be surprisingly helpful. Look out too for a young Tom Wilkinson in a brief exposition role early on.

Director Michael Darlow maintains the suspense with positively Hitchcockian levels of skill, especially in the crucial sequence in which the crime Raskolnikov planned leads to an even worse one. He also makes clever use of a limited television budget to give a fine sense of the squalor of overcrowded St Petersburg, even if it should be said that the production values are actually superior for a BBC drama of the time. He deserves to be better known: starting out as a documentary director, most notably of Johnny Cash in San Quentin and of the most horrifically memorable episode of The World At War, as well as a dramatized biography of JMW Turner with Leo McKern, he subsequently went on the make the respected Suez 1956, Mr Pye, and Bomber Harris, but Crime and Punishment represents some of his best dramatic work.

The BBC returned to Crime and Punishment in 2002 with a two-part adaptation starring John Simm as Raskolnikov. By that point the BBC had learnt the benefits of investing in better production values to boost overseas sales and the main selling proposition of the update was that it was filmed in St Petersburg. Despite that, and a solid supporting cast, especially Ian McDiarmid, reminding the world that there is far more to him than Palpatine, playing the investigator very closely to how Dostoevsky intended, it is not as memorable as the 1979 version. If there was always an element of staginess to the original which is highlighted by comparison with the remake - and it has to be said that the cliche of using discordant strings to suggest madness is overdone - perhaps that is no bad thing because it may be a story that is best told theatrically rather than realistically. After all the best scenes are basically theatrical scenes in which great actors use dialogue and expression rather than action and effects to draw the viewer in. This seems increasingly a lost art in television, which is a pity because such scenes stick in the mind far longer than those with lots of shouting and explosions. Watching Hurt, West, and Middlemass is not a passive experience: it is becoming part of the drama.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on February 25th, 2025. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.