Manchild

2002 - United KingdomReview: John Winterson Richards

What does it mean to be a man in the 21st Century West? Most of us have never had to go off to war or hunt for our food or endure constant hard manual labour or perform any of the other physically demanding functions for which the male of the human species in particular is supposed to be biologically adapted. As a result, many today are uncertain of their roles - even if, being men, they are unlikely to think of it that way, or indeed at all - and live in a state of permanent adolescence with no higher purpose than to enjoy themselves.

Television does not help in this regard - we grow up watching actors simulating manly things instead of doing them ourselves - and at the same time it mocks the immaturity to which it has contributed. The helpless male, as opposed to the practical woman, is now an almost compulsory trope of modern comedy.

As its title suggests, Manchild is very much part of this trend, but it is a superior example, thanks to a very superior cast. It is basically Men Behaving Badly for 50-year olds. Of course, they just happen to be affluent, good looking, successful 50-year olds, because no one wants to watch poor, ugly losers, not even poor, ugly losers - perhaps them least of all. Losers have proven comedic potential when they still have plenty of time to change for the better, as in Men Behaving Badly and a host of other recent comedies about feckless young men, but depressing they are when they have become all they are ever likely to be.

Our four heroes in Manchildare, if anything, how all those feckless young men would prefer to imagine themselves when they are older, even if most seem uninterested in putting in the effort to get there.

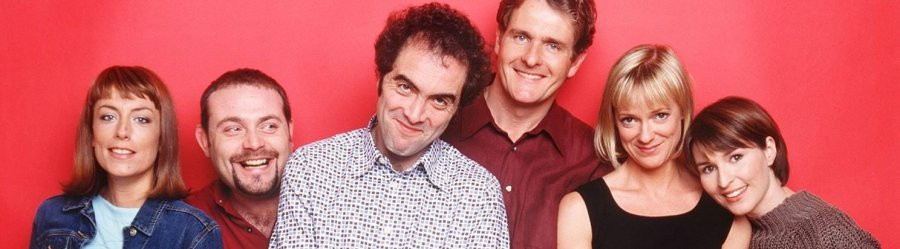

Terry, a divorced stockbroker, is played by Nigel Havers as what can only be described as a Nigel Havers charmer, except that Terry is increasingly aware that he has to make the charm work harder as he gets older.

James, a Harley Street orthodontist, is also divorced and is in general a slightly sleazier version of Terry. He is played by Anthony Head, who seemed to get a lot of slightly sleazy or villainous roles after he returned to the UK following his huge success as the heroic Giles in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. British television had its revenge.

Entrepreneur and art collector Patrick appears to be the wealthiest of the gang, possibly because he is a committed lifelong bachelor. He dates but is not as predatory as Terry and James. He is played by the great Don Warrington, fondly remembered as Philip, the "Chief and son of a Chief" from Croydon, in Rising Damp.

Gary, played by Ray Burdis, made his money in decking, and while his friends all appear to be middle class, he has, or adopts, a definite working class persona. He also differs from them in that he is married. He loves his wife of 24 years, but seems to be paranoid about his marriage getting stale - one cannot help thinking that the influence of his friends is not healthy in this regard.

The other three are actively on the prowl. It has been truly said - by a lady novelist - that a man needs at least two of three things to attract women: "dish, dash, and dosh." None of our trio are as dishy as they once were, but they have no shortage of dosh, so it all comes down to dash. Here is where much of the comedy lies, because Terry and James in particular are not quite as dashing as they like to think.

They make the mistake of pursuing much younger women and end up making fools of themselves. Even when they have some success, they have little in common with the girls they pick up, so nothing lasts. Indeed, it is fairly obvious nothing is ever going to last for either of them. It is suggested very strongly that both are responsible for breaking up their respective marriages through their Peter Pan complexes.

Christine Kavanagh and Frances Barber are both class acts as the wives they abandoned and who do not seem to miss them at all. Lindsey Coulson is agreeable Gary's down to earth better half. Roger Allam has a superb guest slot as an obnoxious old "friend" of the four who ends up inadvertently putting a lot of things in perspective.

Everything is still seen from the quartet's point of view. Terry often "breaks the fourth wall" to address the camera directly or provides a "voice over" in order to give us the benefit of his philosophical musings. These are frequently rather pretentious and are as often as not contradicted by what we see played out on screen.

Great use is made of clever cutting, musical cues, film references, fantasy sequences, and other imaginative devices, reflecting the rather unreal state of mind in which all four live.

The production values are outstanding, with an extraordinary amount of location work for a British comedy series, giving a credible evocation of both modern London and modern affluence. Someone really seems to have spent some money on this show.

Yet its real strength remains the cast and the characters - and its celebration of the enduring friendship between them that is at its heart and that makes up for the grosser moments. There is a real Four Musketeers chemistry between the protagonists. If the selfishness and superficiality of Terry and James can get a little wearing at times, there is consolation to be found in Gary's simple decency and Patrick's deeper reflection - they are respectively the Porthos and the Athos of our little band.

Although the focus is on Terry, as the d'Artagnan figure - because Havers is the biggest name in the cast - it is Patrick who is by far the most interesting of the quartet, and Warrington who gets to do most of the dramatic heavy lifting. The loss of his mother is a genuinely powerful event amid all the farce, and there is great truth in how this is followed by a sudden irrational urge to procreate that goes against his lifetime of avoiding commitment.

Patrick also gives us what is perhaps the defining image of the theme of Manchild when he enjoys a fleeting moment of existential ecstasy just standing in a river in an expensive new pair of waders. In the end, it is Patrick who realises the importance of having dreams, and of actually making something - possibly with our own hands as our ancestors used to do. The others latch on to this when they realise, to their horror, they have no dreams of their own.

To be strictly accurate, that is not quite the end. The show actually finished - perhaps unexpectedly - on a crassly materialistic and insensitive, but typical and oddly appropriate, note from Terry.

For, being honest, half the fun in watching Manchild is luxuriating, vicariously, in the affluence it is satirising. The show is absolutely right that money is far from the most important thing in life, but it is easier to say that when one has enough of the stuff lying around to spend six or seven figure sums on a whim. So Patrick buys a salmon run knowing nothing about fishing, James invests in art despite having absolutely no taste for it, Gary contemplates buying a boat with no idea what to do with it, and Terry comes up with two and a half million for a small mansion with a large garden in the Home Counties with a vague notion of it being a base for the family he abandoned. We should all have that sort of midlife crisis.

For all its high quality - those who liked it tended to like it a lot - this obviously expensive show never found a mass audience, nor did it carve out "cult" status in its own niche. The language and the fairly graphic representations of sex probably put some viewers off, and may have shocked fans of Havers, Head, and Warrington who expected something more family friendly. At the same time, its primary target market, middle aged men, may have been put off by the usual "men are idiots" ideology. The title Manchild was therefore probably a mistake.

There seems to have been an effort to market it in American as "Sex in the City for Men."If so, it was very misleading. Apart from an obsession with sex and casual affluence, the two shows have little in common. For one thing, Manchild is a much classier act, above all in its players.

Yet the show did have a strange afterlife in the States four years after its cancellation in the form of a pilot for an American version set in LA with a very high calibre cast - James Purefoy, the director Kevin Smith, and John "Chris in the Morning" Corbett from Northern Exposure. It is a pity that it was not picked up for a full season because that might have been interesting.

It is an even greater pity that there was not more of the British original. While it had its flaws - and there were times when it got its tone jarringly wrong and became positively distasteful - it told some truths that are rarely heard on television.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on August 27th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.