Rhodes

1996 - United KingdomReview: John Winterson Richards

After the - possibly unfair - negative reception accorded to its take on The Borgias in 1981, the BBC retreated from the sort of epic historical dramas in which it had set the global standard in the 1970s. It was only in 1996 that it attempted to return to the genre with Rhodes- which proved such a critical and ratings disaster that the Corporation was frightened into another retreat that lasted many years.

There are two big questions about Rhodes. The first is how did anyone with responsibility for a budget of millions ever imagine that the South African-based British diamond magnate and Arch-Imperialist Cecil Rhodes would appeal to a mass audience in the 1990s? A hero to many in his own time, Rhodes is practically unknown to most people today, and of those who are aware of him, many hold such negative views that they would be unlikely to invest eight hours in a "miniseries" in which he was the protagonist. Meanwhile, those with more positive views of Rhodes were put off by the - correct - assumption that the BBC were going to do a hatchet job on him.

It was therefore a hugely expensive project with no obvious target market. It should have been no surprise to anyone that it tanked.

This begs the second of the two big questions about this gigantic failure: did it deserve it? The short answer is "Not entirely." Viewed purely as television, Rhodes has much to commend it, but also many faults.

It is, unavoidably, the 1990s looking back on the 1890s. As usual, one can detect a certain sense of smug moral superiority in the script. While it may be justified in drawing attention to things that happened then which would be condemned today, a little humility might be in order. After all, those who follow fashionable opinions today would probably have followed fashionable opinions back then when they were completely different. We might also reflect that, if our civilisation manages to survive our own mistakes, we do not know what our descendants will think of us in a hundred years time. Perhaps our ancestors may look better than us by then.

So, in terms of drama, if not necessarily of moral philosophy, Rhodes has the right to be judged by the standards of his own time. Otherwise, we will not be able to understand him and enter into his story for those eight hours.

In particular, we have to remember that the current general consensus that invading another country solely for the purpose of conquest is wrong dates only from living memory. It was a legal fiction established in 1945 as a pretext to help give leading Nazis the hanging they richly deserved. At the time, the four Allied Powers doing the hanging all held huge areas of land that they had acquired by precisely those same methods not so long before.

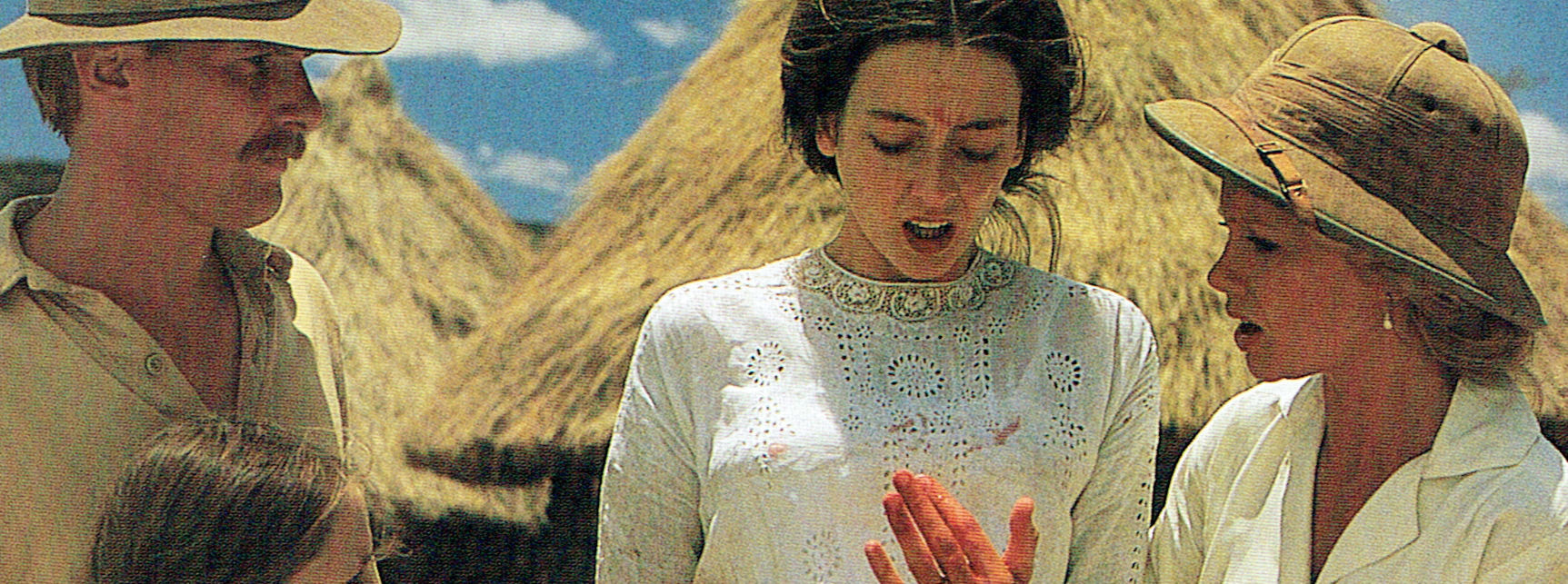

In this context, Rhodes' conquest of the country which, with his usual modesty, he named "Rhodesia" - all of today's Zimbabwe and Zambia - was not out of accord with what was being done by his own country's government, or by the governments of practically all the major European Powers and the United States. (It is perhaps worth noting that the Battle of Wounded Knee took place in the United States while Rhodes was building Rhodesia, and the United States is today the only one of the Powers not to have returned to the descendants of the original inhabitants most of the lands it took forcibly from native peoples in the 19th Century.)

Nor must it be imagined that the people of the lands he conquered were peaceful natives armed only with fruit as Captain Blackadder would have us believe. The dominant Matabele were a powerful and militaristic branch of the famously ruthless Zulu confederacy, and their own invasion of the future Rhodesia a few years previously was far bloodier than Rhodes' incursion.

This is not to defend or justify Rhodes. On the contrary, it is only when we judge him within the context of his time that the real case against him becomes apparent.

Thus, while stripping the Matabele of their political Sovereignty was no more than what they had recently done to others, Rhodes' subsequent "confiscation" - legalised theft - of their cattle was simply low and greedy. So was the imposition of a Hut Tax in cash by Rhodes the Prime Minister of Cape Colony, obliging native Africans, who had no cash, to seek work in the mines, where they were cheap labour - for Rhodes the diamond magnate and his friends.

This sort of thing was considered very bad form even by the standards of the time. However, the Rhodes script, like most modern criticisms of the man, prefers to focus on more anachronistic grounds of complaint. We are invited to sympathise with the Matabele impis charging the Maxim guns of Rhodes' private army when the truth is that they would have been a great deal less sympathetic to anyone not armed with machine guns and breech loading rifles.

At the same time, the script, in its eagerness to show us what a bad man he was, fails to show us that he was also a remarkable man. Arriving in South Africa with almost nothing, he made a fortune in the diamond fields through hard work and enterprise, and became a Member of the Cape Parliament at 27 and Prime Minister of the Colony at 37, while making occasional trips back to Britain to study as a mature student at Oxford.

More importantly, he was a man of vision concerned with more than just his own aggrandizement - even if he obviously had a very healthy interest in that too. If some aspects of his vision are unlikely to find favour with many today, it has to be said that other aspects might have been better than what Africa, Britain, and the world actually got in the century following his death. Rhodes identified as a political liberal, and his view that "progress" justified seizing natural resources from people who were not exploiting them productively was the other side of the coin of his passionate and sincere belief in education as a force to advance "civilisation," which found concrete form in his lavish endowments of universities, including the Rhodes Scholarships. There might indeed have been an interesting psychological and political drama to be found in exploring the apparently conflicting aspects of his character and ideology.

None of this comes through in Rhodes. Instead of a flawed but fascinating hero, we are offered a thoroughly unsympathetic protagonist about whom it is increasingly difficult to care.

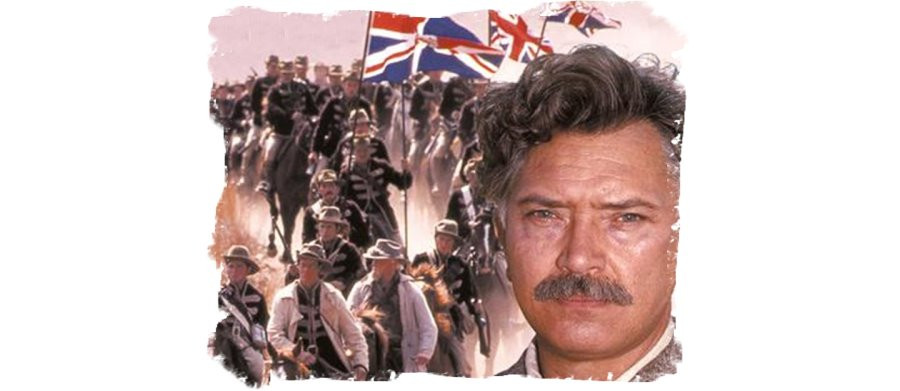

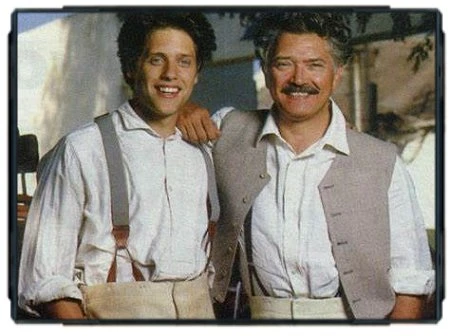

All credit then to Martin Shaw who, with little help from the script, throws himself into the title role and manages to convey the complexity of the man quite effectively. Shaw is a hard actor to categorise. In many ways he seems to have spent his whole career trying to live down The Professionals. An effective stage performer, he can sometimes be needlessly stage-y on television, but he can also be very subtle and his delivery of a telling line is often second to none. Here he gives a good sense of Rhodes' presence and restless energy.

The BBC being the BBC, whispers of Rhodes' alleged homosexuality are treated as established fact when in truth there is absolutely no real evidence to support them. Rhodes never married, but the same was true of many active men in the ultra-masculine "Boy's Own" culture of the British Colonies at that time - not least Rhodes' enforcer Dr Leander Starr Jameson who was a noted womanizer.

Jameson is played by the then ubiquitous Neil Pearson, who certainly captures some of the adventurer's charm and drive, even if the script never really gets to grips with what made him tick. This is a shame because Jameson is a character straight out of John Buchan - except any sensible novelist would reject him as too unrealistic. Successively a highly qualified physician, an honorary chief of the Matabele, de facto Governor of Rhodes' private kingdom, a convict, the subject of Kipling's poem 'If,' Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, a member of the Privy Council, and a Baronet, he deserves a television programme of his own. Whether he would be hero, villain, or loveable rogue is a matter for debate.

Frances Barber is watchable, as she always is, as a dodgy aristocrat on the make. Joe Shaw looks the part as the young Rhodes - as he should, being Martin Shaw's son. Ken Stott turns up as Barney Barnato and Oliver Cotton as Joseph Chamberlain. Otherwise the cast is not especially distinguished, but it did the job it was paid to do.

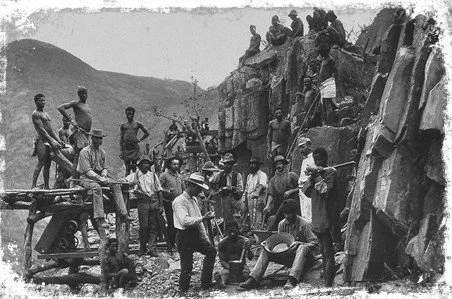

If it fails as drama, Rhodes succeeds as spectacle. It was said to be the most expensive British television drama ever made at that point and it shows. Whatever else, the money is there on the screen.

Extensive use of locations, some beautiful photography, and detailed authenticity in props and costumes give the whole project a look that is positively cinematic. The word cinematic can also be applied to Alan Parker's rousing score, which seems to be influenced by John Barry.

Indeed, every department seems to have excelled. That only makes it all the more tragic that all this effort and expertise on the part of so many skilled professionals was wasted on a concept that was, as should have been obvious, commercially and dramatically flawed from the start.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on May 31st, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.