The Stand

1994 - United StatesThe Stand deserves credit for having the courage to engage with cosmic issues

Review: John Winterson Richards

Anyone arguing that Western culture is in decline could do worse than to present a comparison of the two television adaptations of Stephen King's novel The Stand, the highly regarded original in 1994 and the considerably less well regarded remake in 2020, as Exhibit One. It is not a significant milestone in itself but it is representative of widespread problems with roots deep in our current cultural industries.

First of all the very existence of the remake is emblematic of the decline of an industry that it is investing in so many unwanted remakes, "reboots," and sequels rather than in original ideas. Apart from anything else, they are depriving themselves of source material for future remakes, "reboots," and sequels. It is not only short term strategic thinking but bad short term thinking.

More importantly, these remakes are almost invariably inferior to the older versions, shining a glaring spotlight directly on declining craftsmanship. Of course, the technology of production has improved enormously, but it seems writers and producers have forgotten the art of storytelling. The likes of Robert McKee warned us decades ago that this was happening, but it has come to pass in spite from those Cassandra-like predictions. This is doubly annoying because most of the writers and producers responsible trooped to McKee's seminars back in the day, so they have no excuse.

A very long list of recent feature films and television shows could be quoted in support of this point. Most were expensive flops destined to be forgotten quickly, but in some ways it is those that were not entirely without merit that are the most demoralising. For example, the Oscar nominated remake of All Quiet on the Western Front was a well made film with some clever ideas of its own, but it misses the point of Erich Remarque's novel entirely and it is hard to remember only a few months later, something that can never be said of the original adaptation in 1930 or even of a more credible television remake in 1979.

Much the same can be said of the 2020 remake of The Stand. As our own review of that miniseries pointed out, it was by no means without merit, but rewatching the 1994 version for the first time in almost thirty years, one is reminded of how much better the original is and why saying that is not simply the rose tinted glasses of nostalgia.

Both versions stick relatively close to the novel by the standards of television adaptation, which can be quite free. The book is not typical of King's usual work. Contrary to his usual habit of writing tightly plotted tales set in the darker corners of the modern world, in The Stand he paints on a huge canvas, and leaves one hoping he would do so more often. The story is essentially in two parts. The first is about how a virus escapes from a government lab and wipes out practically the whole human race. The second is about the struggle between literal Good and Evil among small communities of survivors.

The tone of these two parts is very different. The first is in effect a political thriller, but as the story progresses it takes on more of a mystical quality. These two very different aspects should not belong in the same story, but King weaves them together will great skill, exploiting his particular talent of making the supernatural feel realistic to great effect.

"Show, don't tell" may be the most important rule in scriptwriting. So the 1994 version made the sensible decision of playing it straight with a linear timeline. That way we get to see the rapid collapse of human civilisation happening before our eyes, with a convenient date stamp appearing from time to time to emphasise just how rapid it is.

What we are shown is all too credible. At first the government lies in what they know is a futile attempt to keep the populace calm. This is doomed to fail, so the government becomes increasingly authoritarian and desperate in its attempts to maintain control by brute force. This too is doomed to fail, so we get to see the total collapse into anarchy.

This, arguably the best part, is what the 2020 remake missed out almost completely. The remake does better in the later episodes as the more supernatural elements come increasingly into play but, even there, the 1994 original sets the standard and is not surpassed.

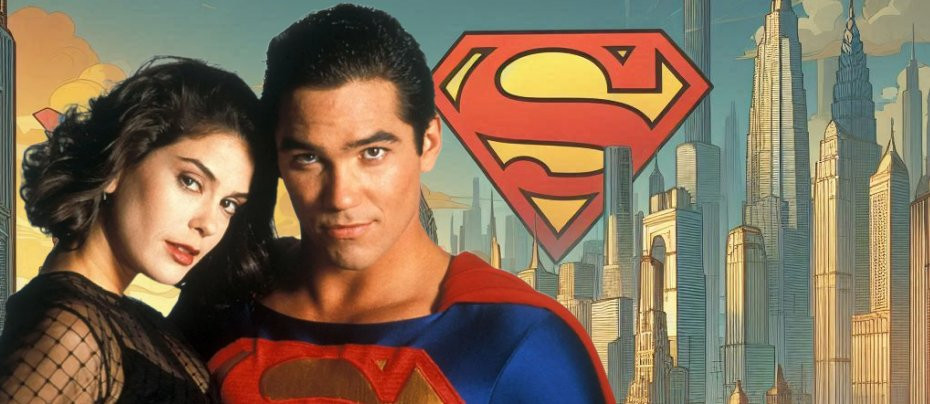

Both productions benefit from talented casts. However, the 1994 version has a definite advantage in its leading man, Gary Sinise. As an actor, he always gives the impression that his characters have several layers to them, and this ability serves him particularly well here. His Stu Redman, superficially a standard "everyman," has a bit of a wild, rebellious edge to him but is at heart a decent man, and when events force him to mature he turns out to be a natural leader. This reads like a list of contradictory cliches, but Sinise is able to bring these different elements of the character together very convincingly, and a cartoon hero is turned into a real human being.

Molly Ringwald is Frannie Goldsmith, his love interest, and it is not her fault that her character as written is not very interesting or well rounded. The remake has the same problem. Although well into her twenties, Ringwald seems to be playing her as a teenager, which was still her default at this point in her career - and, to be fair to Molly, probably what she was hired to do. As a result, her romance with Sinise is one of the few false notes in the production: they do not feel like a natural couple because she comes across as too young for him.

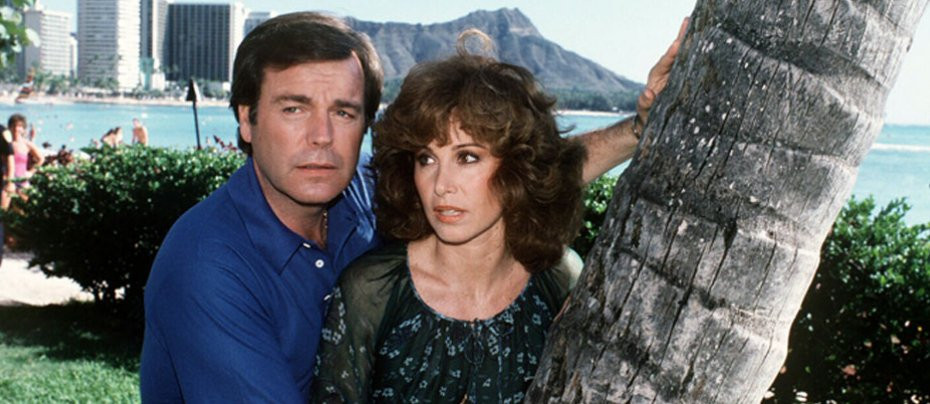

By contrast, Rob Lowe, another teen star from the 1980s, shows how he has matured with a positively loveable performance as an archetypal "guileless fool," complete with a wide-eyed innocence and a saintlike response to all the horrors happening around him - and to him. Lowe, as he also proved in Parks & Recreation, is a versatile and very talented actor, at his best when he is allowed to play something more than his usual Handsome Guy part.

Jamey Sheridan is magnetic as Randall Flagg, the literally Satanic villain, and it is a pity that he has not been allowed to stretch himself in similar roles since then, instead of supporting character parts as in Law & Order:Criminal Intent. The always watchable Miguel Ferrer brings typical nuance to Flagg's apparently loyal right hand man, so that we are not entirely certain which way he might jump before the end.

Ed Harris and Kathy Bates are predictably effective in unbilled guest parts as the human faces of, respectively, the decaying, despairing government and the justifiably suspicious citizenry. Their respective fates are perhaps symbolic. It is certainly the opposite of criticism of both actors that we could have done with seeing a lot more of them and finding out more about their characters. As it is, they are sacrificed to keeping up the pace and one can hardly deny that this is something the 1994 production does well.

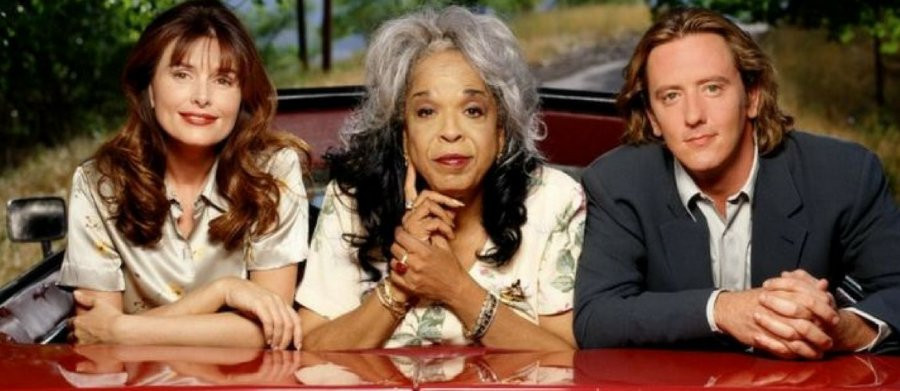

It does, however, have to be said, that looking at the 1994 production with 2023 susceptibilities, one cannot help wondering if the virus differentiated between racial groups, because it is very noticeable that, apart from real life married couple Ruby Fee and Ossie Davis, the two communities of survivors are overwhelmingly white. The more racially diverse casting of the 2020 production is therefore justified in purely dramatic terms not only because the demographics of the United States have changed considerably in the intervening decades but because it is also probably more representative of how America actually looked even in 1994.

There is one other respect in which the 2020 remake is superior. Things were wrapped up very quickly and conveniently in 1994 as the story rushed to a happy ending that felt a bit contrived. The 2020 version took its time and, staying closer to the novel, ended on a more realistic note, implying that old problems would remain, or resurface, even after the supernatural triumph of Good over Evil. Human beings would still be human beings.

Nevertheless, The Stand deserves credit for having the courage to engage with cosmic issues and, at the same time, the skill to make the conflict down to Earth with believable people doing believable things which favour one side or the other in the cosmic struggle.

The 1994 production also deserves credit for giving the whole thing a proper sense of scale. There are apparently over a hundred speaking parts and filming took place in locations all over America, giving us a fine sense that this was a national event (and presumably a global one, but, this being an American production, what is presumably happening elsewhere is never really addressed).

Above all The Stand is, in both versions, an emotional experience that leaves us with a lot of intellectual questions. How likely is it that our civilisation might collapse as quickly and completely as it does here? How would we as individuals act in such an event? Would we choose Good or Evil? If we are too quick to assume we would choose Good, are we being honest with ourselves? Who are we, really, when we are under pressure? There are very few recent productions that invite us to engage with serious issues, and that is indeed a symptom of a culture in decline - which may yet be reversed if we take the time to study the superior culture of the past, of which the 1994 version of The Stand is itself a fine example.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on October 6th, 2023. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.