The Stand (remake)

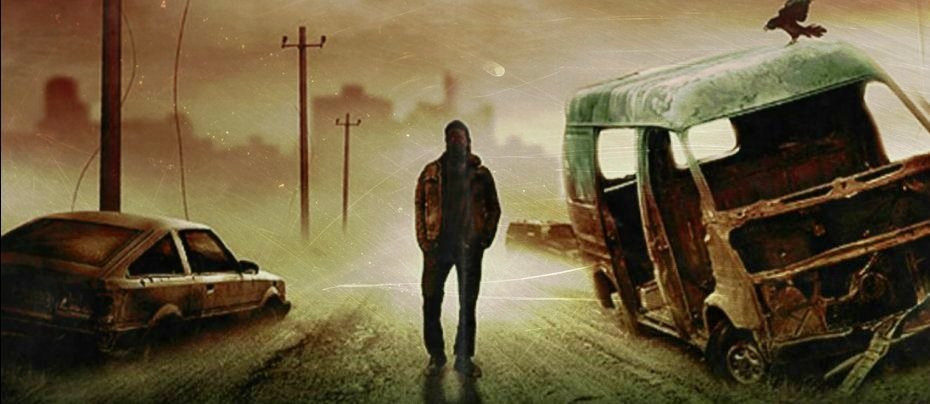

2020 - United StatesHow would the survivors react to a total collapse of civilisation?

The Stand review by John Winterson Richards

Stephen King took himself out of his comfort zone with his most ambitious, and arguably his most accomplished novel, The Stand. Unlike the relatively intimate, even claustrophobic horror tales for which King became famous, The Stand is an epic set in a "post-Apocalyptic" America, and, although the supernatural element remains, it rises to the theological. In concept it transcends genre very impressively.

The novel was adapted successfully into a powerful "miniseries" back in 1994 and one would have thought there was no need to remake it. Sadly, we now live in a time when need and customer demand are less important than the flawed but common assumption among entertainment industry executives that - in spite of a huge pile of evidence to the contrary - remakes and "reboots" offer a more reliable business model than investing in new content.

So The Stand was remade in 2020 - and the remake was generally hated. This was due in part to the growing, and completely understandable, public contempt for that bad remakes business model, especially when applied to a "miniseries" that was generally remembered with respect.

It was also due in part to a structural error that had the "timeline" jumping all over the place in the opening episodes. Techniques such as "flashbacks" and starting a story "in media res" - literally "in the middle of the thing" - can be very effective when used properly, but they can be disastrous when overused. The important thing is that the viewer needs to retain a sense of who the characters are and what the story is. The remake failed to establish that until a relatively late stage, by which time it was too late for most viewers.

However, the main reason for the general hatred of the remake was not all its fault: it was the victim of some horribly bad timing totally beyond its control. The premise of the piece is that most of the human race is wiped out by a global pandemic, and it just happened to finish filming only days before coronavirus restrictions came into force.

Topicality can be a gift to a production, as it was, for example, to the original British version of House of Cards, which was broadcast just as Margaret Thatcher was being forced from power. One could see the fiction being mirrored in real life as one watched. The opposite happened to The Stand. Viewers could see the chaos and stress caused by a pandemic with an overall fatality rate of less than 1%, but The Stand postulated a fatality rate of over 99% - and suggested that life for the survivors was really not that bad. Nor did they seem to be suffering much in the way of emotional damage.

This is a great weakness of the whole "post-Apocalyptic" genre, especially on television. Shows like Revolution, The Last Ship, and Sweet Tooth imply that, after some initial disruption, life would go on pretty much as before. In The Stand everyone looks clean and well fed, and food is still easily available from shops, even if going shopping actually means looting abandoned buildings. In reality, everything edible would be gone within days of the electricity supply breaking down. The psychological consequences of suddenly losing everyone you know would be as devastating as the economic collapse. The living might indeed envy the dead.

The remake might have got away with its sanitised version of global tragedy almost any other year, but not in 2020 when even pandemic became politicised. It did not help that, at the same time, one segment of the market might have been put off by the religious themes, while a completely different segment may have seen the usual Hollywood political subtext in some details of the script (a chant of "Make them pay" was suspiciously reminiscent of the "Lock her up" heard in relation to Hillary Clinton at Donald Trump rallies). In the end, it was difficult to see any target market for this project except, perhaps, Christians who vote Democratic.

Yet if one is able to watch it and judge it objectively without this context, and can be bothered to sit through the fractured storylines of the first few episodes, one might be surprised by how good it gets. The original "miniseries" may still be better, but, viewed in its own terms, the remake retains much of its power.

This is mainly because King's story has such a strong premise. How would the survivors react to a total collapse of civilisation? Would they try to rebuild it, or would they become victims of the worst possible combination of nihilism, anarchy, and tyranny? To rebuild would require an act of faith, but what sort of faith could survive a total catastrophe? Could they rebuild better or would the mistakes of the past be repeated as new power structures were developed?

These are big questions, and they generate some surprisingly intelligent dialogue in the script. It engages positively with faith without either proselytizing or cynicism. The ideal community seems at first a sort of libertarian theocracy that becomes a democracy, and it seems idyllic, especially relative to the only alternative that is shown, but there a hints of practical difficulties to come.

Most of the characters have some depth. There is real doubt for a while about on which side of the brutally stark good/evil dichotomy some might eventually end up. Some of the "good" characters are tempted quite seriously and some of the "evil" characters have moments of doubt or at least regret, which, nevertheless, do not appear to save them.

The two leading characters are the least interesting. The obvious hero is played by James Marsden, who knows how to play the amiable good looking guy because he has been playing him for twenty years now. One can sympathise with his rival in love who complains that all he has to offer the heroine is his dimples. One misses the hints of complexity that always emanate from Gary Sinise, who played the same role in the previous adaptation.

If it is impossible to recall anything negative about Odessa Young as said heroine, it is only because there is nothing very memorable about her character in the first place. Things just happen to her.

The two characters that really stick in the mind are the personifications of Good and Evil played by Whoopi Goldberg and Alexander Skarsgard, which is only right, because the story is really about them rather than the not-quite juvenile leads, who are little more than eye candy.

Goldberg does some of her best work as a Harriet Tubman-esque calm Wise Old Black Woman, who gives the impression she has seen and done it all. It is because everything about her seems so natural and normal that it seems natural and normal even when she turns out to be a Prophet. By contrast, everything about Skarsgard's Randall Flagg is slightly unsettling, even when he is literally charming. As he proved in Generation Kill and True Blood Skarsgaard excels as magnetic personalities with something slightly "off" about them.

Flagg appears in several King stories as an analogue of Satan, even if he deliberately does not use the name. He is Satanic in the most ancient meaning of the word, not only a tempter but an accuser - he knows everyone's weak spots. The scenes in which a character he is trying to influence might go one way or another are some of the best.

Greg Kinnear is great as a jaded Professor and the only complaint is that we do not spend more time with him, exploring how a professed atheist becomes the equivalent of one of the Angels sent to Sodom in the Book of Genesis. American football player Brad William Henke is extremely likeable as a big man with a big heart and a learning difficulty that forces him to repeat everything at length - which he manages to make a lot less irritating than it sounds.

The always watchable Heather Graham and J K Simmons have strong guest slots, but they add little to the main story. Amber Heard is an unlikely 30-year old virgin. Fiona Dourif makes a big mark in a fairly small role as an unhinged MC. Dad would be proud.

There are some outstanding visual sequences. A beautiful "discovering America" montage with pleasant easy listening music reminiscent of a 1970s road movie is intercut with constant subtle references to death. A spectacular sweeping aerial shot takes us from the Hoover Dam to Las Vegas in seconds (they are actually just under an hour apart by road). Las Vegas itself, at its most deceptively attractive by night, is transformed very convincingly into a vision of Hell, where its inhabitants destroy themselves though their own joyless hedonism and mindless violence - insert your own punchline here.

There are weaknesses in all this. It is difficult to imagine how the Las Vegas "community," for want of a better word, could sustain itself for long. Indeed, even the idealised community established by our protagonists seems to be without visible means of support. Someone needs to start planting crops almost immediately.

Nevertheless it is to the credit of The Stand that it prompts one think seriously about such things as the nature of civilisation and how faith in something, whether true or false, is needed to bind people together - and if is not faith in truth it will be faith in falsehood.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on April 13th, 2022. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.