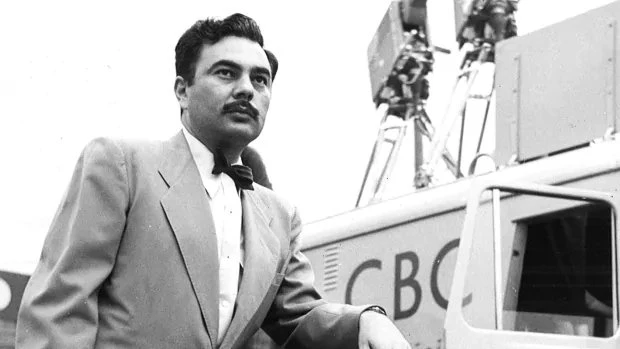

Sydney Newman

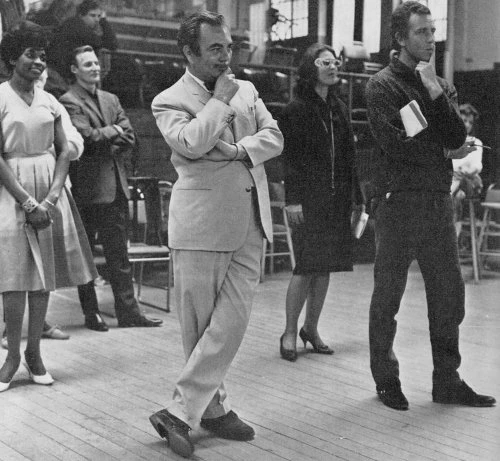

When Sydney Newman came to England from his native Canada in 1958, no one could have predicted that he would become one of the most influential programme makers of the 1960's. His influence changed the outlook of a generation that was looking for change and should have elevated him to far greater things. Instead, this giant of the TV industry disappeared into relative obscurity by the end of the very decade that had seen his greatest success.

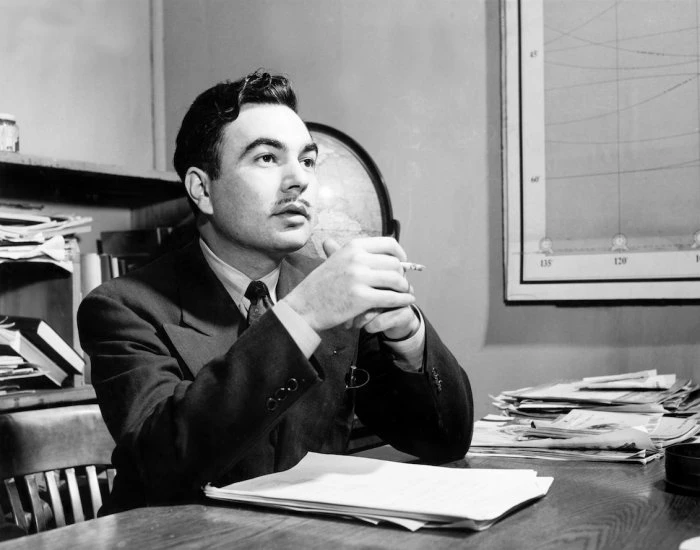

Born in Toronto on 1 April 1917, Newman studied commercial art at the Central Technical School, before becoming a stills photographer and artist, painting promotional posters for the movies. It was whilst doing this job that Newman became interested in the cinema, and in 1941 he joined the National Film Board of Canada as a splicer boy. During the Second World War he progressed to become an editor and ultimately director of training films for the Canadian Government.

In 1945 Newman produced his first film, Canada Carries On, before being promoted to Executive Producer, and becoming responsible for some 300 documentaries between 1947 and 1952. During this time a Film Board secondment to NBC in New York had taught him the tricks of the American's trade in television, and he employed these when, in 1954, he was made Supervisor of Drama at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Newman realised that because of cultural inequalities, audiences at that time were far more inclined to be followers of cinema drama rather than television drama, which they regarded as too highbrow and stuffy. The brief he handed out to his writers and directors was to create television that the viewers could identify with by reflecting issues that were familiar to a mass audience. His over-riding dictate was that televised drama should make plain statements about real everyday situations, and real everyday people. What Sidney Newman proposed would eventually become known as Kitchen Sink Drama.

In the UK, television had started in the 1930's although it was not until the end of WW11 that a regular service became more widely available. This was BBC television, which, until the mid-1950's had no competition whatsoever. Then in 1955, a number of Independent Television companies were awarded franchises to begin broadcasting. Unlike the BBC, which was one corporate body, ITV was made up of a dozen or so production companies which made pre-recorded programmes for sale to each other and overseas. Whereas the BBC was funded by a licence fee, ITV had to generate its own income, which required advertisers, who, in turn, would require a maximum audience. To achieve the best results the independents looked towards the people that they regarded as the experts in product promotion, the Americans. ITV wanted to introduce a style of programming that would dent the hitherto complacency of the BBC. They wanted TV to attract that maximum audience. And they succeeded.

In 1958 ABC TV (which had the weekend franchise for the Midlands and the North), approached Sydney Newman and offered him a post in control of its drama series Armchair Theatre. The series had been launched in 1956 and had proved relatively successful, but now ABC wanted Newman to bring to it the same qualities that he'd introduced in Canada. Newman accepted, not for financial reasons, but because he felt it presented him with a new and irresistible challenge. He'd identified the same class differences that he'd come across in North America. "At the time, I found this country to be somewhat class-ridden." He later recalled. "The only legitimate theatre was of the 'anyone for tennis' variety, which, on the whole, presented a condescending view of working-class people. Television dramas were usually adaptations of stage plays, and invariably about upper classes. I said, 'Damn the upper-classes -they don't even own televisions!' My approach was to cater for the people who were buying low cost things like soap every day. The ordinary blokes the advertisers were aiming at."

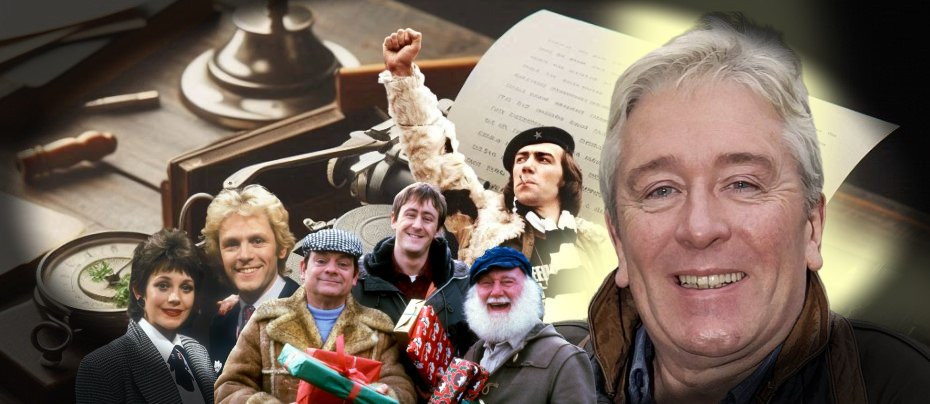

The results spoke for themselves. Under the helm of Newman, the weekly dramas reached the top ten ratings for 32 out of 37 weeks between 1959 and 1960, with audiences of 12 million viewers. Other successes followed with the science fiction anthology Out Of This World, the children's series Target Luna, Pathfinders in Space, Pathfinders to Mars, Pathfinders to Venus, and a spy series that would evolve into one of Britain's best loved and best remembered programmes of all time-The Avengers.

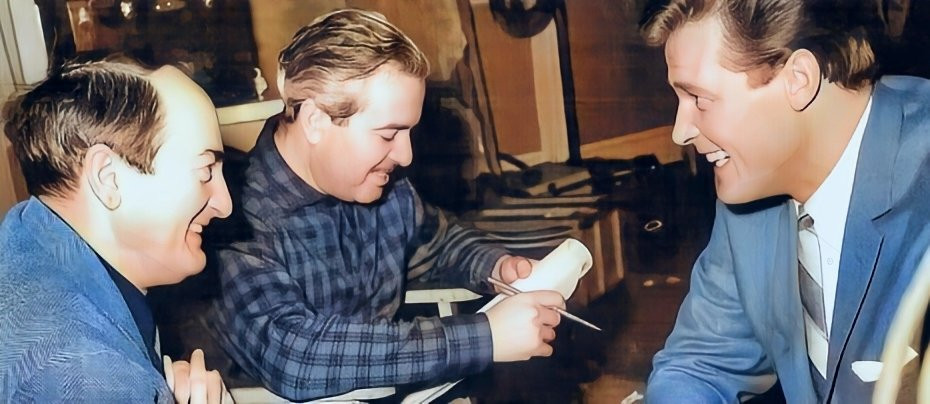

By 1961 the BBC were suffering from the success of the independent stations, and so it was that Sir Hugh Greene, the corporation’s Director General, asked three of his top executives to sound out the Canadian about joining the Beeb as Head of Drama. Accordingly, around Christmas of that year, a series of discreet meetings took place in a Marylebone pub and, successively, Kenneth Adam (Director of Television), Donald Baverstock (Assistant Controller of Programmes) and Stuart Hood (Controller of Programmes -Television) had met with Newman to discuss the post. The outcome was that Newman would go to the BBC as soon as ABC would let him go, or if the worst came to the worst, in April 1963 when his ABC contract ran out. Until then the BBC drama department would continue under the headship of Norman Rutherford. Unsurprisingly, ABC were reluctant to let Newman go.

Once again it was not the financial reward that lured Newman away from his post. Indeed, he took a drop in salary of £3,000-but the chance to take control over the entire dramatic output of the BBC, with virtually unlimited executive powers, was one that he couldn't resist.

Writing in Contrast Magazine (Autumn 1962), before Newman had taken up his new post, Philip Purser, television critic of The Sunday Telegraph, who had interviewed Newman prior to his article, informed the reader about the qualities that attracted the BBC to Newman and what he’d be facing when he arrived there.

Clearly Newman has qualities highly valued by the BBC’s new directorate. Newman seemed to me to be the first man to impose a recognisable house style on a play series, the first to bring a consistently three-dimensional quality to his productions, the first to insist on every play being ‘about’ something, having relevance to the Big World outside.

He went on to talk about the different kinds of play he liked to put on, a curiously revealing list in its mixtures of idealism and practical considerations. He wanted to see more plays about industry, about class antagonism, about Britain’s changing position in the world. He’s always been a sucker for science.

How he’ll deal with the BBC’s respected tradition of classic productions is obviously one of the things that will be watched keenly. He’s said he hopes to look at classics afresh through contemporary eyes.

New writing for television will still be his main preoccupation; the old ‘Armchair Theatre’ aim at dramatising ‘the dynamic changes taking place in Britain today’ has yet (he feels) to be really attained. He likes serials and will keep the BBC tradition going.

All these individual projects are secondary to the organisational problem that faces Newman. How will he fit in with the classical civil service administration of the Corporation? How will he exercise power in his own department? The uneven strands in BBC TV drama over the years (marvellous one night, abysmal the next) sprang largely from the unwieldiness of a method which made individual directors answerable only to one overworked head; some were virtually anonymous producers. Newman is likely to compartmentalise … encouraging competition between each strain of drama.

All in all, it looks as if BBC TV is acquiring someone very much in the image it has lately been fashioning itself: professional, good-humoured, competitive, self-reliant, in touch with the times and at heart on the side of the system.

After seeing out the remainder of his contract with ABC, Newman took up his new post in December 1962.

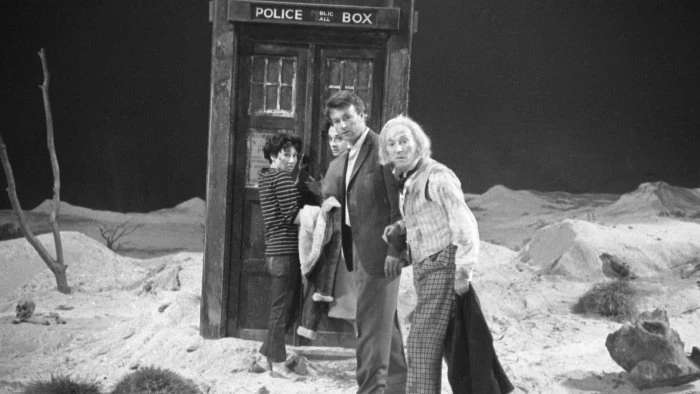

His first task at the BBC was to break up the existing structure of the Drama Department and reform it into the Drama Group. This new section covered three new departments, Series, Serials and Plays. Under the old system a Producer was expected to produce, direct and liaise with the writer on his script. Under the new system each Producer was allocated a Director and Story Editor, leaving him free to oversee the production in a far more strategic manner. By 1963, with the restructuring in place, Newman was free to develop new programmes for the BBC to challenge what was clearly ITV's supremacy. One of the first programmes that Newman suggested was a tea-time drama series aimed at the Saturday gap between the highly popular sports programme Grandstand and the equally popular pop music programme Juke Box Jury. "I vaguely recall a children's classic drama series that filled the slot." Said Newman. "Charles Dickens dramatisations, that sort of thing. I decided that this could be moved to Sunday afternoons if the Drama Department could come up with something more suitable. So we required a new programme that would bridge the state of mind of sports fans, and the teenage pop music audience, while attracting and holding the children's audience accustomed to their Saturday afternoon serial." That serial was to pass into television legend. It was Doctor Who.

Newman described his basic outline for Doctor Who thus; "It had to be a children's programme and still attract both teenagers and adults. Also, as a children's programme, I was intent upon it containing basic factual information that could be described as educational, or, at least, mind opening for them. So my first thought was of a time-space machine with contemporary characters who would be able to travel forward and backward in time, and inward and outward in space. All the stories were to be based on scientific or historical facts as we knew them at the time." Newman passed a memo on to Donald Wilson whom he'd appointed as Head of Serials and told him "Here's a great idea for Saturday afternoons." Over the next few months Wilson developed the idea with Newman and BBC staff writer C.E.Webber, fleshing out the characters and creating the scenario for a pilot episode. To produce the programme Newman appointed Verity Lambert who had been on his Armchair Theatre staff at ABC. To appoint a woman producer in 1963 was a bold step. Newman: "She had never directed, produced, acted or written drama, but by God she was a bright, highly intelligent, outspoken Production Secretary who took no nonsense and never gave any."

A pilot of Doctor Who was made that, in Newman's opinion, did not come up to scratch, and so he took the unprecedented step of ordering script changes and a complete re-shoot. Doctor Who debuted on 23 November 1963 to great critical acclaim. Newman's faith in the series, and indeed in his newly appointed producer was fully justified. "My only firm order to her was 'On no account will I permit BEM's -bug eyed monsters of cheap-jack fiction. They're out.' Weeks later, a timid Miss Lambert came and told me about the Daleks. I exploded." The Daleks were the epitome of the BEM's that Newman so much despised. They were also an instant success and launched the series to new heights. With ratings passing the eight million mark the whole country went Dalek mad, children in school playgrounds around the country were imitating the creatures’ grating voices and shouting "Exterminate, Exterminate!" Weeks later Newman called Verity Lambert into his office once again and told her "You obviously understand this series far better than I do." And from that moment on he left her alone to get on with it.

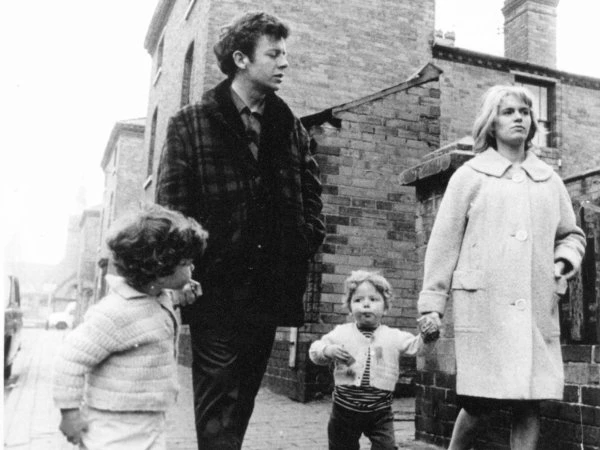

When British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan visited South Africa in 1960, he spoke of a 'wind of change' that was blowing through that particular continent. Indeed, that analogy is probably the most apt description of the entire decade that followed. The 1960's is still the decade that is looked back on with the greatest affection by those who lived through it, and often by those who wish they had. Freed from the constraints of world war and as a result of the baby boom that followed the end of hostilities in 1945, it was the era in which youth found its voice and adults had no choice but to listen. In Britain in particular, the abolition of National Service in the late fifties, meant that for the first time that century a generation of men had no military background, producing a huge change in attitude. Reflecting a growing awareness, and possibly the confusion of Britain's social and political changes, were writers such as John Osborne, Fay Weldon and David Mercer. Many of these authors found their voice on Sydney Newman's BBC drama anthology The Wednesday Play, which was conceived out of the experience of his success with Armchair Theatre. In 1966 The Wednesday Play brought us one of the most significant pieces of work that has ever been transmitted on British television. Written by Jeremy Sandford and directed by Ken Loach, this single drama had such a profound effect on its showing that Britain would never be the same again. The play was called Cathy Come Home.

Cathy Come Home told the story of a young northern lass who made her way to London, met and married a local lad (Reg) and soon found herself the mother of three children. As the story unfolded the family was torn apart by the fact that they had no permanent roof over their heads, following Reg's accident at work and his subsequent struggle to find re-employment. It showed how they fell headlong into a downward spiral of squalor, from a pokey caravan to an eventual hostel for the homeless. Torn apart by this the couple separated and eventually Reg stopped paying for their keep, until Cathy and her children were thrown onto the streets. The despair experienced by Cathy as her children were forcibly removed from her by Social Services touched the hearts of the nation. Scenes were kept to a minimum and the play quoted true housing figures throughout. Shot in documentary style with a handheld camera, a soundtrack devoid of music and punctuated with urban noise, many viewers thought that they were watching a true story unfold. The stark realism of Cathy Come Home led to angry calls for action to prevent such circumstances. The changes in social attitudes and awareness were significant, and the issues addressed were discussed in Parliament. As a direct result of the play the homeless charity, Shelter, became an important voice in housing matters. Never before or since has one single piece of drama had such an effect on an entire nation.

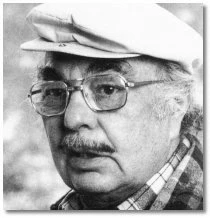

Over the following years Sydney Newman presided over the twice weekly soap opera The Newcomers and a series to rival ITV's Avengers, an outlandish series about a Victorian gentleman frozen in ice and bought back to life in the swinging sixties - Adam Adamant Lives! In 1967 Newman also presided over a series which won a clutch of prestigious awards as well as world-wide acclaim - The Forsyte Saga. It was to be his last great success. Later that year, despite having been offered a new seven-year contract by the BBC, Newman announced that he was leaving to take up the post of Producer at the Associated British Picture Corporation. In November he was awarded the Desmond Davis Award for Outstanding Creative Work in Television. He left the BBC the next month, never to return. Newman's arrival at ABPC coincided with the virtual collapse of the British film industry. During 1968 his profile was a low one and the four projects he planned never even got off the ground. Following a takeover of ABPC by EMI in June 1969, Newman was dismissed. Bitter over his "18 months of futile waste", and reluctant to return to the BBC despite being offered an Executive Producer role by the Corporation, Sidney Newman returned to Canada.

Relocating from his native Toronto to Ottawa, Newman became Special Advisor to the regulatory Canadian Radio-Television Commission. Soon after, he moved to Montreal to become Chief Commissioner of the National Film Board of Canada. When in July 1975 his contract came to an end, it was not renewed. At the age of 62 Newman returned to England once more where he set up home in London. During the 1980's his contribution to Doctor Who became recognised thanks to a number of publications charting the beginnings of the series, which, twenty years later, was still going strong. In 1986 he met incumbent BBC1 controller Michael Grade to offer some ideas for changing Doctor Who and requested that his name be added to the programmes closing credits. Nothing ever came of that meeting and by the end of the decade the BBC decided to stop making the series. Sydney Newman died in October 1997. One can only wonder how he’d feel today, knowing that since its revival in 2005, Doctor Who has become one of the BBC’s biggest money-makers of all time with a following all over the globe.

With Newman's passing, the final curtain went down on an entire age of quality and innovation in the field of popular television drama. Bold and imaginative, wide-ranging and consummately professional, Sydney Newman was a true giant of the early golden age of British television creativity.

Published on February 20th, 2019. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.