Tourism in the Classic Doctor Who Series

Article by Andrew O’Day

A tourist can be defined as someone who travels to a distant place for pleasure, often on holiday, and who frequently engages in sightseeing and visiting museums, for instance. This article will look at tourists in the diegetic worlds of serials from the classic Doctor Who series – usually the Doctor and his companions – and will show how they cannot remain tourists. The article will probe how this is important to the notion of the television viewers of the programme as travellers, of watching the programme being a leisure activity and of picking up merchandise connected with the series.

The approach taken in this article differs from previous work on Doctor Who and tourism which tends to focus on fan visits to places where the programme was made (see for instance, Beattie, 2013). As Paul Booth puts it, ‘fan tourism’ has traditionally focused on…the way that fans journey to a location familiar from the diegesis of a media text’ (2021: 206). This fan tourism, according to Booth, is not a practice restricted to fans of Doctor Who: fans of The Prisoner visit and stay at Portmeirion, Harry Potter fans visit Oxford and Dallas fans take trips to Southfork (2021: 206). Booth cites other work on this type of tourism (such as Linden and Linden, 2016; Geraghty, 2018; Williams, 2018). Booth, however, argues that in the case of Doctor Who, Chris Chibnall and the production team ushered in fan tourism not of locations but of commodified fan experiences.

This article develops on Tat Wood’s (2007) argument: he contends that the Doctor and his companions are permitted to view the universe for their pleasure and instruction, with the Doctor’s open-ended curiosity to learn the secrets of the universe, by virtue of the fact he has some active agency in the worlds he explores rather than just being a spectator. This, argues Wood, resists the temptations of imperialist ‘stamp-collecting’ display and taxonomy. The Victorian contrast between objectivity and active agency ran through works which emphasised spectacle such as that of the Lumiere brothers and Gabriel Veyre, at the origins of cinema, and active agency was later apparent in the early BBC’s Zoo Quest’s (1954-64) non-fiction presentation. Certainly, the Doctor left his home planet of Gallifrey in a stolen TARDIS (standing for Time And Relative Dimension In Space) to see the universe since, as he remarks in ‘The War Games’ (1969), he was ‘bored’, in ‘The Daleks’ (1963-64) he tricks his fellow travellers so that he can explore the alien city, and in ‘The Reign of Terror’ (1964) he states that he has the universe to explore. Perhaps best illustrating the point of delighting in viewing the universe, though, is in ‘Colony in Space’ (1971) when the Doctor tells the Master: ‘I want to see the universe, not to rule it’. The Doctor has active agency and purpose when he visits a place, however, rather than just going there just to see it, as highlighted in ‘The Sensorites’ (1964) when he refers to what a ‘spirit of adventure’ has been had, in ‘The Tomb of the Cybermen’ (1967) when the Doctor tells his new companion Victoria that their lives are different and that no one else can do the things that they do, and in ‘The War Games’ when he tells the Time Lords that while they have been content to simply observe he has been fighting evil throughout the universe.

That the Doctor is not a typical tourist is borne out by many further individual serials. For example, ‘Marco Polo’ (1964), ‘The Keys of Marinus’ (1964) and ‘The Chase’ (1965) are early examples of travel narratives, however in ‘Marinus’ the Doctor and his companions are on a mission to find four keys to restore the Conscience of Marinus, a computer which maintains law and order, as opposed to enjoying sights, and in ‘The Chase’ they are fleeing the Daleks, who have their own time machine, from place to place, in what Jonathan Bignell calls ‘picaresque adventure’ (2023: 119). In episode three of ‘The Chase’, the Doctor and his companions are contrasted with a group of visitors who are being shown the Empire State Building by a tour guide. Furthermore, although the first episode of ‘The Gunfighters’ (1966) is titled ‘A Holiday for the Doctor’, this is a play on the name Doc Holliday and upon landing in the Wild West the Doctor visits him in desperate need of a dentist to cure toothache, though arguably Steven and Dodo are at first enthusiastic tourists. The Doctor is then mistaken for Doc Holliday and the Doctor, Steven and Dodo are placed in a number of perilous situations. ‘The Space Museum’ (1965) is also an interesting case: the Doctor and his companions arrive in a museum with numerous exhibits which include spacecrafts from different periods – prefiguring ‘The Seeds of Death’ (1969) – but they are not typical tourists as they try to make sense of a series of bizarre events which culminates with them seeing themselves in an exhibit. They realise that they are seeing a possible future and when they arrive in the present they must act to prevent themselves from becoming part of the exhibit which includes them assisting to stage a revolution. There is also the case of what is typically a tourist space in our world – Madame Tussauds – being subverted in ‘Spearhead from Space’ (1970) and the Doctor and his assistant Liz are not tourists there but are investigating. We shall now see a number of examples of typical tourism in serials and how tourism is displaced.

‘City of Death’ (1979) was filmed in Paris (the first Doctor Who to be filmed abroad) and at first the Doctor and Romana are on a ‘marvellous’ ‘relaxing’ holiday. It is not often that the Doctor and his companions are seen simply relaxing, an early example being at the start of ‘The Romans’ (1965). The first scene of ‘City of Death’ begins with a panning shot from left to right of a desolate prehistoric landscape until the alien Scaroth’s spaceship becomes visible, which will explode on take-off. This panning shot is then repeated as the action moves to Paris and takes in flowers and finally the Eiffel Tower in the background. The Paris scenery differs completely from the desolate landscape of the first scene and also joins the two scenes together suggesting what Paris will become if Scaroth’s scheme to alter time and make sure that the ship explosion which led to the creation of man does not occur. There are further shots which take in the Parisian landscape, such as the Eiffel Tower again from a train that the Doctor and Romana are on and of the Doctor and Romana running through the streets with upbeat music accompanying this. The Doctor indeed says to Romana ‘never mind about the timeslip, we’re on holiday’, however, as this is Doctor Who, this becomes impossible to ignore and their holiday is cut-short in their efforts to thwart Scaroth’s plan. By contrast, in later serials filmed abroad – ‘Arc of Infinity’ (1983) in Amsterdam, ‘Planet of Fire’ (1984) in Lanzarote and ‘The Two Doctors’ (1985) in Seville – the Doctor is not positioned as a tourist enjoying a relaxing holiday but is on a mission to these foreign locales. Rather in the case of ‘Arc of Infinity’ the backpackers Colin Frazer and Robin Stuart are tourists of Amsterdam before they are thrown into unsettling adventure and in ‘Planet of Fire’ Peri is ‘bored’ out of her mind in Lanzarote and is not willing to explore caves with her mother and a woman from the hotel. So, for the most part, the Doctor is not a character who can relax as a tourist of foreign places and although ‘City of Death’ begins in this manner it very quickly becomes an adventure serial.

‘The Leisure Hive’ (1980) begins on Brighton beach which is alien to the Doctor and Romana who come from another planet. Brighton beach is a common tourist attraction in our world and the opening, like the first shot of Paris in ‘City of Death’, sees the camera panning from left to right at some length. However, here the Doctor gets the season wrong and it is a freezing windy day causing Romana to remark to K9 that she doesn’t think much of this Earth idea of recreation. The opening is not disconnected from the rest of the narrative as it sets up the idea of tourism that will be central to the rest of the serial.

Because the serial shifts to Argolis, ‘the first of the leisure planets’ as K9 has given Romana a complete list of ‘the recreation facilities’ in the galaxy. There is a slow zoom out from Brighton beach through space and the scene shifts to Argolis, a planet which attracts visitors, including the Doctor and Romana. At first, we see the visitors looking at the outside of Argolis, devastated by radiation, from the safety of the hive. The visitors also watch games such as non-gravity squash on a screen which are taking place inside the Generator and are not edited recordings. The Doctor and Romana are quickly plunged into a series of dangerous situations and so cannot remain tourists on a pleasurable excursion.

The 20th anniversary special ‘The Five Doctors’ (1983) sees the Fifth Doctor and his companions Tegan and Turlough as tourists visiting one of the wonders of the universe, The Eye of Orion, following on from the end of ‘The King’s Demons’ (1983). It is described as ‘beautiful’, and is so beautiful in fact that the first scene set outside sees Turlough sketching the landscape. When Tegan asks whether they can stay there, the Doctor says ‘for awhile. We could all do with a rest’, however, events conspire against the Doctor’s and his companions’ wishes where a mysterious figure uses a time scoop to transport many incarnations of the Doctor and numerous companions to the Death Zone on Gallifrey. This turns out to be Lord President Borusa who uses the characters as pawns in his game to enable him to get to the Dark Tower and claim immortality.

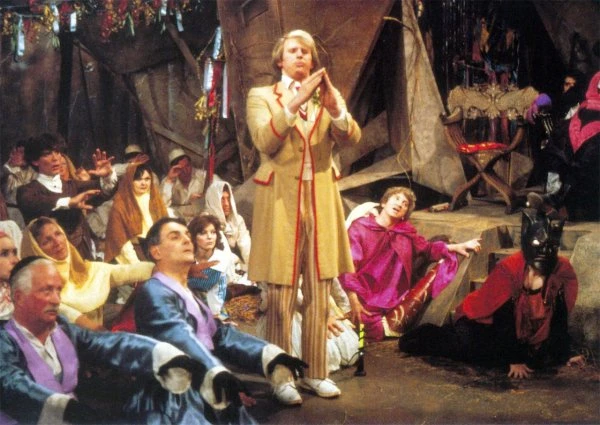

Two further serials, both by the same writer, deal with tourism. ‘Paradise Towers’ (1987) positions the Doctor and especially Mel as tourists. Images on the TARDIS scanner excite Mel to want to visit the Towers, longing to take a dip in the swimming pool. But while this serial plunges the Doctor and his companion into danger it differs from previous ones examined in that the tourist destination itself turns out to be a run-down tower block, far removed from the Doctor and Mel’s expectations, where the architect of the Towers, Kroagnon, whose mind has been imprisoned in the basement, seeks to take control of his creation by taking over the body of the Chief Caretaker. ‘The Greatest Show in the Galaxy’ (1988), meanwhile, begins with a robot appearing in the TARDIS and playing an advert for the Psychic Circus on the TARDIS scanner, what Ace calls junk mail. It taunts Ace, who finds clowns creepy, to visit the Psychic Circus and this is a tourist attraction which we see a number of characters journeying toward in the first episode. In this case, the Gods of Ragnarok are behind the sinister circus.

Certainly, what these serials show, and what the unmade serial ‘The Nightmare Fair’ set in Blackpool would also have exemplified, then, is that the Doctor and his companions cannot remain ‘tourists’ but are plunged into perilous adventure, as prescribed by the format of the programme. This is very well illustrated by a couple of serials where the Doctor and his companion are planning to be tourists but where this is thwarted: namely ‘Death to the Daleks’ (1974) and ‘Horror of Fang Rock’ (1977). In ‘Death to the Daleks’ the Doctor and Sarah Jane Smith are en route to Florana for a holiday with Sarah in holiday attire for a warm climate. But the TARDIS suffers an energy drain and lands on the planet Exxilon where the Doctor faces his greatest enemy, the Daleks. In ‘Fang Rock’ the Doctor is taking Leela to Brighton (which he eventually reaches in ‘The Leisure Hive’) but the TARDIS materialises elsewhere by a lighthouse where there are sinister goings on. ‘The Seeds of Doom’ (1976) differs in that the serial ends with the Doctor and Sarah en route for a holiday – Sarah, holding a beach ball, looks forward to getting a tan. But they find themselves back in Antarctica where the serial began with the joke ‘have we been here before or are we yet to come?’. ‘Delta and the Bannermen’ (1987), however, illustrates again that tourism is replaced with danger: on what seems like a package holiday, a spaceship is disguised as a bus which serves the same purpose as Cully’s tours to the island in ‘The Dominators’ (1968), and is filled with tourists on the way to Disneyland in the USA. But the bus collides with a satellite and is diverted to a holiday camp in South Wales with the Doctor following. The merciless Bannermen, led by Gavrok, in pursuit of last of the Chimerons, Delta, threaten the harmony of the camp in a deadly manner.

The television viewer is a traveller of the universe as we join the Doctor and his companions and we are ‘visiting’ all these locations for pleasure. The shots of Paris in ‘City of Death’, for example, indeed position us as sightseers and fits in with Catherine Johnson’s (2005) notion of television being watched with a gaze by contrast with John Ellis’ (1982) argument that television is characteristically viewed with a glance while involved in other household activities. Furthermore, while the Doctor is not a tourist of Amsterdam, Seville and Lanzarote, the sights are there for us, such as when there is a long chase through the streets of Amsterdam and when Lanzarote doubles for the planet Sarn. Additionally, when images appear on the TARDIS scanner in ‘Paradise Towers’ and ‘Greatest Show’ these are metatextual since they also appear on our television screens.

It is worthy of note that seeing from a distance and contemplating a landscape are associated with tourism in some of these Doctor Who serials for characters and for the television viewer. We have seen, for example, that Turlough sketches a landscape in ‘The Five Doctors’, while in the earlier serial ‘City of Death’ the Louvre houses art, however the art that is of interest to characters in the serial is the portrait of the Mona Lisa. Fakes of the Mona Lisa are being painted to be sold so that Scaroth, in the human form of Count Scariloni, can fund his experiments to go back in time and prevent the destruction of his spacecraft. Conversely, the television viewer is provided with views of the Parisian landscape. Indeed, places on a television screen are framed as is landscape painting displayed in a frame, which the art gallery visitors in ‘City of Death’ (played by John Cleese and Eleanor Bron) would call ‘exquisite’.

The television viewer also visits locations in the series more broadly. The programme is a series of serials and the central conceit is that in each new serial the protagonists land in a new environment in the machine, the TARDIS. There are exceptions to this rule, largely in the Jon Pertwee era of the programme in the early 1970s where the Doctor was for a time exiled on twentieth century Earth. It has long been recognised that the television viewer identifies with the companion and just as they are whisked away so are we. In ‘Planet of Fire’, for instance, Peri wants to leave Lanzarote and travel as a tourist to Morocco, but at the end of the serial she joins the Doctor on his travels and we accompany them from our homes.

It is key that one of the Doctor Who’s involving tourism is titled ‘The Leisure Hive’. It has long been recognised that television is largely consumed by the viewer for leisure. Work has been done on the relationship between television and leisure time in a variety of countries, such as in Britain and in the United States, using the method of audience surveys (see, for example, Robinson 1969). In the United Kingdom, ‘the arrival of television…in the postwar period coincided with rising standards of comfort’ in the home (Rees, 2019).

Furthermore, Harry Draper argues that ‘Snakedance’ (1983) involves tourism with its bazaar where the world is a pantomime staged to celebrate the end of the Sumaran Empire and the vanquishing of the Mara. While tourists visit Manussa the Doctor is, in this case, not a tourist since he finds himself on the planet to combat the Mara. Draper intriguingly makes the case that the Mara is not simply history but also merchandise (Draper, for example, refers to the plastic snake as a prop that is paraded about by the Manussan public and there are also miniature plastic snakes which are rattled in front of Tegan). Draper proceeds to note that if the production values appear unrealistic and artificial that this encapsulates Manussa perfectly. Unfortunately, Draper does not go so far as to argue that the snakes are cheap tourist souvenirs bought on holiday and that these are paralleled with TV fan merchandise (even if not of plastic snakes).

This article, then, has approached the notion of Doctor Who and tourism in a new way to established criticism as well as drawing upon what has already been written. To date, most work in this area has concentrated on ‘fan tourism’ such as to locations used in the programme, although work has also been done on tourism and merchandise. We have seen here how the theme of tourism dealt with in a few serials is enhanced by camerawork. This investigation has been fruitful as it has told us a lot about the rules of the series and about its audience as well as about the audiences of television more broadly. Finally, further work can be done on tourism to take into account New Who where, for instance, in ‘Fugitive of the Judoon’ (2020) Ruth is a tour guide before she is revealed to be a prior incarnation of the Doctor.

References

‘The Doctor Who Experience’ (2012-) and the Commodification of Cardiff Bay’ by Melissa Beattie in Matt Hills, ed, New Dimensions of Doctor Who: Adventures in Space, Time and Television (London: I.B. Tauris, 2013, 177-191), ‘The epic in the everyday: television and Doctor Who ‘The Chase’ by Jonathan Bignell in Sarah Cardwell, Jonathan Bignell and Lucy Donaldson, eds, Epic/Everyday Movements in Television (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2023, 116-39), ‘Outside the box in the Chris Chibnall/Jodie Whittaker era: Doctor Who’s experience economy and tourism’ by Paul Booth, in Brigid Cherry, Matt Hills and Andrew O’Day, eds, Doctor Who – New Dawn: Essays on the Jodie Whittaker Era (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021, 206-221), ‘The Good Sumaran’ by Harry Draper in Tides of Time (45/46 2020), Visible Fictions: Cinema, Television, Video by John Ellis (London: Routledge, 1982), ‘Passing Through: Popular Media Tourism, Pilgrimage, and Narratives of Being a Fan’ by Lincoln Geraghty in Christine Lundberg and Vassilios Ziakas eds, The Routledge Handbook of Popular Culture and Tourism (New York: Routledge, 2018, 203-13), Telefantasy by Catherine Johnson (London, BFI, 2005), Fans and Fan Cultures by Henrik Linden and Sara Linden (London: Palgrave, 2016), ‘Television, gas and electricity: Consuming comfort and leisure in the British home 1945-65’ by Emily Rees in Journal of Popular Television (7: 2, 2019, 127-143), ‘Television and Leisure Time: Yesterday, Today and (Maybe) Tomorrow’ by John P. Robinson in The Public Opinion Quarterly (33: 2: 1969, 210-222), ‘Fan Tourism and Pilgrimage’ by Rebecca Williams in Melissa A. Click and Suzanne Scott eds, The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom (New York: Routledge, 2018, 98-106), ‘The empire of the senses: narrative form and point-of-view in Doctor Who’ by Tat Wood, in David Butler, ed, Time and Relative Dissertations in Space: Critical perspectives on Doctor Who (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007, 89-107).

I thank Garron Martin for useful suggestions, Professor Jonathan Bignell and Dr Matthew Kilburn for commenting on an early draft, and my friends: Tim Harris, Richard Harris, Simon Heritage, Adam Emanuel, Joshua Nicholson, and as always my Muse Dr Anjili Babbar for inspiration. And to Zac with affection.