Doctor Who

2005 - United KingdomIt’s hard to deny that Doctor Who has been one of the 21st Century’s televisual success stories. Since 2005, the BBC Wales production team has produced and aired over 170 episodes across thirteen series, with the fourteenth airing in 2024. Alongside the main series, there have been animated serials, online exclusive shorts and humorous short skits for charity. Doctor Who dominated the BBC’s Christmas Day schedule for thirteen years before an unexpected shift to New Year's Day, returning to the Christmas schedules as part of a run of specials in 2023. Doctor Who has spawned three official spin-off dramas – Torchwood, The Sarah Jane Adventures and Class, and one unofficial spin-off, the Australian K9 children’s drama. The Doctor, his friends and foes now appear nationwide as toys, in magazines, on greetings cards and clothing, and at the height of the series' popularity, the Doctor’s choice of wardrobe had a measurable effect on British men’s fashion. A succession of exhibitions have appeared across the country, along with a live arena tour, an immersive theatrical experience and a Punchdrunk stage play. Not bad for a series that appeared to have lived and died before the end of the 20th Century.

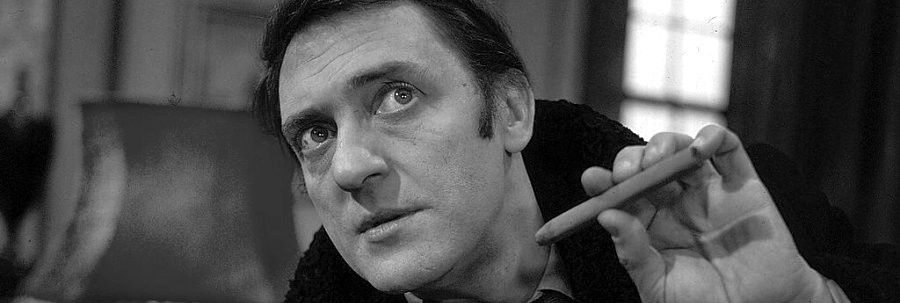

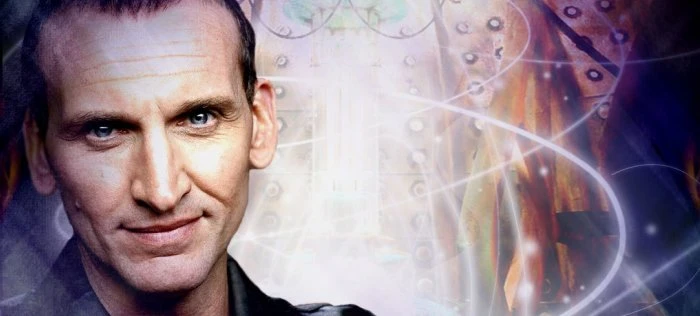

Doctor Who was a success for the BBC throughout the 60s, 70s and early 80s, but by 1989 its viewing figures had plummeted, its place in a modern TV schedule was in question and its cancellation inevitable. In spite of a widely watched 1996 TV movie special and a thriving fan culture that kept the franchise alive across various media, Doctor Who on television seemed extinct. Then, in 2003, the astonishing announcement came from the BBC: Doctor Who was coming back. Back to TV where it belonged, and it was to be overseen by one of television’s most respected writers, Russell T. Davies. TV experts wondered if such an old-fashioned show could be successfully updated. Comedians and tabloid columnists mocked the original’s wobbly sets and rubbish monsters. Fans of the classic show read of developments with bated breath. News trickled out, shocking those who were expecting something like the show they so fondly remembered. Forty-five minute episodes! Short, one-episode stories, instead of serials shown over weeks! Christopher Eccleston as the Doctor - in a leather jacket! Pop star Billie Piper as his companion! Rights had been denied, and the Daleks wouldn’t be in it! What would this new series be like?

We needn’t have worried. In 1989, Doctor Who fell. In 2005, Doctor Who - Rose.

All those concerns evaporated. To survive and succeed in modern television, Doctor Who had to adapt and evolve, just as it always had done. The 25-minute episode format appeared archaic back in 1989; punchy, 45-minute episodes were the way to go, and Rose was a breathless, exciting, funny adventure. Christopher Eccleston, an actor known for his stark, severe style of acting and for serious roles, brought an intensity to the Doctor that we never realised the character needed, yet allowed a rarely-seen humorous side to soften the character, making him someone we would truly love to travel with. Billie Piper silenced her naysayers, imbuing Rose Tyler with an enthusiastic lust for life, tempered by a believable, grounded personality. And we needn’t have worried about the Daleks. They’d be on their way soon enough, but for now, we had the Autons, making their first onscreen appearance since 1971. Rose showed what Doctor Who could be: fast, funny and modern, breaking new ground, yet still embracing its long, rich history. And that was just the first episode.

Watch that first series back again. There’s a nervousness there; the production team don’t know if this is really going to work. This is produced by people with the utmost commitment to their project, but with the knowledge that it could still fail. Television is a capricious medium. Received wisdom, in the early 2000s, was that the family audience no longer existed, and that Saturday evenings were now an almost-unwatched hinterland. Doctor Who reclaimed a whole niche of television, proving that, yes, the kids and their whole families could sit down to watch TV together. Russell T. Davies, as executive producer and lead writer, created a truly successful update of an old property. He reinvented the mythology, ditching years of fluff and paring it down with a new, easy to grasp backstory. The Doctor is an alien, from a people called the Time Lords, who travels through time and space in a ship called the TARDIS, which, due to a malfunctioning disguise, looks like an antique telephone box. The Doctor needs someone by their side, to keep them grounded in the human world, and to keep them from forgetting the good things in their life. Sure, more bits were added on, but at its heart, that’s what today’s Doctor Who is.

Russell T. Davies isn’t the only one who deserves credit for this series. Julie Gardner, his fellow exec. producer, fellow episode writers Mark Gatiss, Paul Cornell, Steven Moffat and Robert Shearman, the cast and the huge crew, all deserve credit. Still, it was Davies’s vision. He retooled the style of the series, rooting it in the mundane and everyday, with frequent trips back to contemporary Britain for visits to Rose’s family and friends. This allowed a strong root for the vital audience identification figure, and also made the fantastical elements of the show seems all the more astonishing by comparison. This is perhaps best illustrated by the second episode, The End of the World. Having visited the day of the destruction of the Earth, five billion years in the future, surrounded by death and destruction and a host of bizarre alien entities, Rose and the Doctor return to Earth and go for chips - and this becomes a vital character moment, where the Doctor opens up about his experiences in the Time War, the mythic new backstory Davies set up for the series.

Not everyone was happy with the new direction, of course. Many hardcore fans disowned the new series, considering it a betrayal of the show they loved. The Doctor kissed his companion, voiced his emotions at length and talked with a northern accent, all things which some fans considered a violation of the show they loved. Others were took a more pragmatic approach; the Doctor was felt to be ineffectual, relying on others to save the day, and relied on his sonic screwdriver too much, removing tension with its magic wand-like abilities. The familiar complaint from the classic series’ heyday, that the series was too scary and was unsuitable for its children-heavy audience, reared its head once again. The acknowledgment of sexuality, including homosexuality, in what was seen as a children’s show, drew criticism from many quarters. The presence of a science fiction show in a primetime slot sat poorly with many in television, who viewed such series as the province of geeky ‘cult TV’ slots. Yet these were minority views, with the viewing figures frequently hitting seven or eight million, a rarity for non-soap television drama at the time. Critics voiced their appreciation of the series, praising the writing and performances. Children adored the adventure and the scares, with girls finding Rose to be a strong, positive role model - a young woman who wasn’t rich or posh, but was still intelligent, capable and strong.

Things couldn’t stay the same forever. Doctor Who was always a series that thrived on change. It’s fascinating to see how the series has developed over the years, sometimes in predictable ways, sometimes not. Most obviously, the Doctor has changed. Eccleston decided, largely due to an unhappy experience filming, to do only a single series, bowing out after his thirteenth episode. Fortunately, Doctor Who came with a built-in get-out clause. In the closing moments of The Parting of the Ways, having saved Rose from the damage she had done to herself ridding the Earth of the Daleks, the Doctor regenerates. Like Eccleston, David Tennant had previously worked with Davies; Eccleston starred as Stephen Baxter in the Church-bating drama The Second Coming, while Tennant had played the eponymous Casanova for the BBC, both of which had been penned by Davies.

Tennant’s tenure as the Doctor propelled the series even further in its popularity. His Mockney Cockney wideboy interpretation of the role charmed audiences and made him into a TV heartthrob. Some found the verbal barrage of this Doctor annoying, but his enormous popularity with fans is undeniable. By this stage, a fully-fledge fanbase had grown up around the new version of Doctor Who, and their love of Tennant’s Doctor was at the root of this. Tennant, as much a fan of the classic series as Davies, was living a childhood dream by playing the Doctor, and it shows. His is a sillier, more over-the-top Doctor, but he still had the darker, damaged side of his predecessor; it wasn’t gone, just hidden. Indeed, in his darkest moments Tennant's Tenth Doctor could be far more ruthless and unstoppable than his predecessor.

Doctor Who is not just about the Doctor, however. It never has been, although the Time Lord came to dominate a series that had, in its formative years, centred around the bewildered humans who were whisked off in the TARDIS. Rose brought the focus back onto the companions. The first two years of the series were viewed primarily through Rose’s viewpoint, a canny decision on the part of Davies and his team. Rose wasn’t the first companion to be strong, interesting and capable, far from it, but Doctor Who on television had rarely been so much about the character so often regarded merely as an assistant.

As we got to know the new Doctor through Rose, the two became ever more involved. They were thick with each other, having the time of their lives, and this was perhaps a mistake. The pair of them could be insufferable at times; there’s a fine line between confidence and cockiness. Yet, when they were finally split up, separated by the boundaries of reality, only the coldest heart failed to be moved. After two years of Rose Tyler and her periphery of friends and family, Doctor Who stepped back to a parade of companions. The third and fourth series each had a regular female companion for the run, who would then drop in and out for the remainder of Davies’s reign as showrunner. This element of the series, with the Doctor having returning friends rather than a strict parade of companions, began in the first series, not only with on-off boyfriend Mickey and Rose’s mother Jackie, both of whom would appear in the show’s frequent visits to contemporary Earth before eventually finding themselves on the TARDIS, but also with Rose’s short-lived flames. The wet Adam (Bruno Langley) existed purely to contrast with Rose and show how much more suitable she was as companion material, but the flamboyant Captain Jack Harkness, played by John Barrowman, was a greater success, returning for both the final adventures of series three and four and heading up four series of his own adult-oriented spin-off, Torchwood.

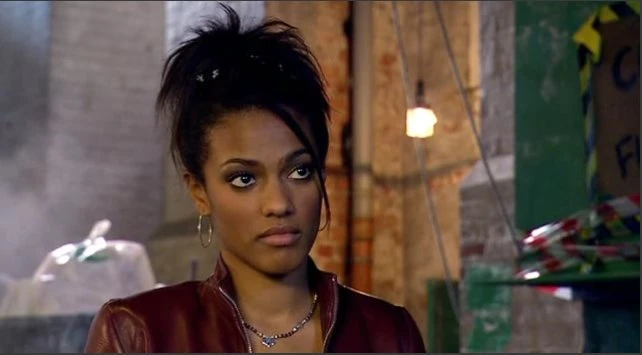

Freema Agyeman had a tough act to follow, coming in as Billie Piper’s replacement. Martha Jones was, on the face of it, more suitable as an adventurer, a highly intelligent, capable doctor-in-training. Audiences failed to take to her in the same way as they had to Rose, although she certainly has her fans. Some of this was down to the vague similarities between the characters; they both fell in love with the Doctor, both have difficult mothers, both represent modern London young adults. More pertinently, Martha was deliberately written as living in the shadow of Rose, and this stopped her character from truly taking off until she was written out of the show, leaving at the end of the third series to live her own life. Nonetheless, she made several return appearances, both in Doctor Who and Torchwood.

Catherine Tate’s turn as Donna Noble is perhaps the series’ most surprising success. Her sudden appearance at the end of series two’s closer, Doomsday, mere moments after the Doctor bid a “final” goodbye to Rose, was certainly a surprise. Many believed her role in the Christmas episode The Runaway Bride to be nothing more than a case of stunt casting (they should have held fire - Kylie Minogue was in it the next one, leading to the highest ratings of the period). Tate remains best known for her comedy work, and was ubiquitous on British television at the time. However, reluctant adventurer Donna proved to be a hit, so much so that the intended one-off companion was brought back to be the regular audience identification figure for series four. Donna is one of the most normal, down-to-earth, realistic characters to have travelled in the TARDIS, and Catherine Tate’s ability to switch between perfect comic timing and devastating emotional displays proved her to be a fine choice for a series lead.

For a series that had taken such pains to avoid referencing old mythology and trivia, Doctor Who was, by its fourth year, developing a great deal of its own baggage. The fourth series ended in a two-part extravaganza which reunited almost all the companions who had appeared in it since the show returned to the screens, bringing in character from the spin-offs and exploring the hinted at mythos of the Time War in more depth than ever before. Russell T. Davies’s approach to the series can be described as “kitchen sink,” in two different ways: not only as in the classic “kitchen sink drama” style of mundane life, and also as in “Everything but the - !” in his approach to barnstorming, budget-busting series finales. They certainly drew in the viewers, but by the fourth series finale, the series was becoming self-indulgent.

Following the fourth series, Doctor Who took a well-deserved break. Again, this led to attacks from fans and journalists, assuming it was a method of quietly cancelling the series, or accusing it of pandering to the commitments of its stars (David Tennant was appearing in a high-profile run of Hamlet during this time). In reality, the production team had been working flat-out for four years, and something was going to give sooner or later. A fresh approach would be needed, and the so-called gap year allowed the show breathing space. The current team could begin wrapping up their era, while the new crew could prepare for theirs. 2009 featured only four episodes of Doctor Who (technically three - the fourth aired on 1st January 2010), plus a short animated serial… not to mention the spin-offs. The two-part finale, The End of Time, acted as both Christmas and New Year specials, temporarily resurrecting the Doctor's people, the Time Lords, from their apparent end in the Time War. Though the episode focused on Bernard Cribbins’s loveable character Wilf, Donna’s grandfather, it too brought back a plethora of familiar faces. Davies, never shy of yanking at the audience’s heartstrings, carefully calculated Tennant's exit for maximum tears.

After three years, with two full series and a run of specials under his belt, Tennant, now one of the most bankable actors in Britain, left the role, his seemingly indestructible Doctor dying from a dose of deadly radiation. He explosively regenerated into Matt Smith. The departure of Tennant acted as a chance to wipe the board, with Davies and his co-execs leaving the show. Steven Moffat, author of some of the most popular episodes of the show, took over as chief writer and executive producer. His interpretation of the Doctor is perhaps more mythic in its approach; although Doctor-worship had reached delirious levels by the end of Tennant’s time, Moffat’s version of the Doctor is truly a force of nature, a powerful element of the universe. Yet Matt Smith, the youngest ever actor to take on the role, plays the Doctor as a stumbling galoot, klutzing his way around the universe. Some disliked his silly, comical take on the role, but they perhaps missed the point: this strange young man in a wonky bowtie is merely a front for an ancient, increasingly powerful alien being who simply wants to travel around and see the universe. In his quiet moments, Smith’s Doctor belies an age beyond the actor’s years.

The bowtie is a visual clue to how the series developed over time. While Eccleston's Doctor was deliberately not-posh and eschewed the eccentric dress sense of the 20th century Doctors, Tennant was more flamboyantly stylish and Smith, in contrast to his youth, wore a very old-fashioned series of costumes, calling back to the earlier Doctors. The series has proved more willing to celebrate its past as it has developed, particularly under Moffat. The first series was at pains to mention as little as it could about the show’s history. Terms from the original series barely feature: TARDIS, Time Lord, Sonic Screwdriver, Time Agent, Dalek, Nestene, UNIT. In the second series, Elisabeth Sladen returned as Sarah Jane Smith, the Doctor’s companion from 1973-76, in a move that had far reaching consequences. She even brought robot dog K9 with her. References to classic serials cropped up. By the fourth series, the Doctor was making offhand references to The Sensorites (a rather obscure 1964 serial), and the Christmas special The Next Doctor treated the fans with a montage of the then full roster of ten Doctors. In the fifth series, Smith's Doctor explicitly identified himself as the eleventh, and William Hartnell, the very first Doctor, made no fewer than four appearances in swift visual winks. The climactic episode The Pandorica Opens featured not only every available monster costume from the past five years, but referenced a dozen other alien races from the classic series and beyond.

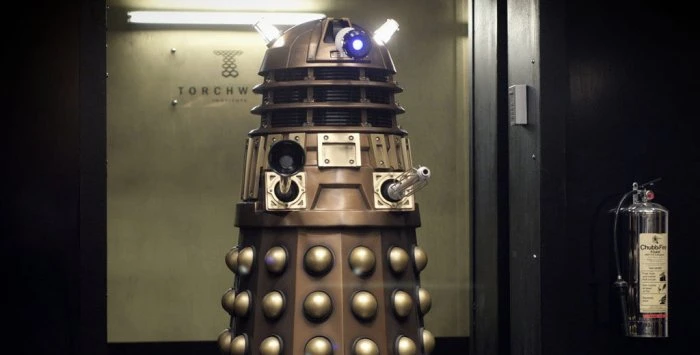

Monsters are, of course, a staple part of Doctor Who’s format and the source of much of its success. The most famous example, of course, are the Daleks. Fan fears that the Daleks wouldn’t be appearing in the new series were allayed when an agreement between the BBC and the Terry Nation estate allowed their use. Although fondly remembered by many, the Daleks had become a laughing stock by the time the original run of Doctor Who had ended. People laughed at their pepperpot shapes, their sink plunger arms, their supposed inability to climb stairs. They’d actually been hovering for years, but it remained a persistent myth. In 2005, an episode going by the straightforward title Dalek revived the metal monsters. Russell T. Davies and Robert Shearman created a script which took all the risible elements of the Dalek design and made a virtue of them. The sink plunger crushed skulls. The silly bumps were explosives. The Dalek flew up stairs, and millions of people saw it happen. People actually became frightened of the Daleks again, and a new generation of children learned to love them. The Daleks returned again that year to face Eccleston’s Doctor in his final adventure, and since then have appeared roughly once every series, either as the main villain of an episode, an extra addition to ramp up the danger, or a cute cameo. An unfortunate side effect, however, is that the Daleks have become the single most frequently defeated villain in the series' history.

This isn’t to say that the series has relied solely on tried-and-tested monsters. The concerted efforts of the writers, make-up artists, prosthetics technicians and the Mill’s CGI crew have come together to create some truly inspired new creatures. While the Davies years relied a little too much on animal-headed humanoids, there were many more imaginative creatures on show. The bulbous, green Slitheen, with their persistent wind problems, were an unfortunate step into childish gross-out humour - they proved far more suited to kids’ spin-off The Sarah Jane Adventures - but other aliens were very successful. The tentacle-faced Ood, created as nothing more than a one-off bunch of mooks, proved popular and flexible enough to return as a major component of the show’s growing mythology, while other memorable creations include the rawheaded Sycorax, the paper-thin Lady Cassandra, the petrifying and petrified Weeping Angels, and the chilling gas-masked zombies of The Empty Child.

These last two creatures sprung from the imagination of Steven Moffat. The second showrunner’s take on Doctor Who proved an interesting development on the first five years of the show. While much of the groundwork was laid by Davies, Moffat proved capable of making wise decisions when it comes to which elements to keep and which to reject. His episodes frequently have a fairy tale quality, and he has proved time and again to have a flair for arresting visuals and child-friendly horror with ingenious central conceits. Moffat took elements of his earlier episodes and reworked them to create his own vision for Doctor Who. Romance was at the heart of his version of the series. The fiery Amy Pond, played brilliantly by Karen Gillan, was the main companion and focus for two-and-a-half years. While she has been an occasional love interest for the Doctor (probably unrequited, but who can say), her true love is Rory, her fiancée, then husband. Played with the utmost sympathy by Arthur Darvill, Rory Williams is a man who would wait two thousand years and transcend death for the woman he loves. He’s surely the greatest hero the series has produced.

The Doctor isn’t immune to the love of a good woman - if good is the word to describe River Song, aka Melody Pond, aka actress Alex Kingston. Introduced in fourth series episode Silence in the Library, River was a surprising returnee to the series under Moffat. She had, after all, died in her first story. This is, however, no issue in Moffat’s universe. The man who invented the catch-all paradox-waiving phrase “timey-wimey,” has written some of the most complex, time-twisting tales in all of Doctor Who’s long history. From the causal loop of Blink, through Amy’s inexplicable childhood and River’s convoluted life, Moffat’s tales of time travel and time dilation have been some of the most talked about in the show’s run.

Was his approach really so complex though? Perhaps not. The fifth series opener The Eleventh Hour, may hinge on time travel, but comes across as deceptively simple, and acts as a perfect introduction to a new Doctor and companion. A whole new cast and crew, more or less, was being sold here, and Moffat’s team managed it with aplomb. The Eleventh Hour, and those episodes that followed it in series five, illustrate some key differences between the worlds of Davies and Moffat. In place of Davies’s council estates and London boroughs, Moffat opts for picturesque villages and rural idylls (albeit largely filmed in Cardiff and environs). Equally British, yet more aesthetically appealing. Moffat introduces his key identification figure, Amy, as a child, before zooming ahead to see the results of the Doctor’s influence on her life. Moffat’s version of the series is more literary than that of Davies. In Moffat’s universe, science takes a backseat and magic does the driving. The Doctor can give himself up in a grand gesture to save the universe, but be brought back by Amy’s fond memories. The laws of time can be suspended, but it’s fine, because the narrative works. The Doctor’s life is a story, and we’re just listening to the telling.

The series has reached worldwide success, particularly in the States. Doctor Who has sold well in the USA since its return, but in the around 2011 American sales rocketed, thanks to a combination of saleable Britishness and canny marketing. Moffat isn’t blind to this, and set the opener to series six in America. The series had previously dabbled with this, in Daleks in Manhattan, but The Impossible Astronaut was steeped in Americana. It’s a clever approach; not only does it appeal to the US audience, making them feel part of the otherwise very British adventure, it also offers the home nation’s audiences something visually new. Series six juggled movie-inspired episodes with more complex emotional plots, and marketed itself with big, confident declarations of intent. The Doctor dies in the first episode! This one’s got pirates in! Let’s Kill Hitler! The Wedding of River Song! Titles and concepts designed to stick out in the TV listings.

Matt Smith's tenure was marked by increasingly involved ongoing storylines. While viewers could casually drop in for an episode, dedicated viewing and reviewing was encouraged, with mysteries getting their pay off after many episodes. The sixth season was essentially a single, intricate story, building up questions, clues and red herrings in preparation for a grand climax. Whether said climax actually worked, or made any sense, is another matter. Series seven, unusually, was split across two years, with the 2012 half bringing Amy and Rory's storyline to a conclusion while introducing Jemma Redgrave as Kate Stewart, the new head of military organisation UNIT who would become a prominent recurring character for each subsequent Doctor. The 2013 half had the daunting task of both introducing a new companion and preparing for Doctor Who's fiftieth anniversary celebrations.

The longest running companion of the revived series, Miss Clara Oswald, was a personification of Moffat's storytelling style. The charismatic and beautiful Jenna Coleman first appeared in a surprise role in the series seven opener, Asylum of the Daleks, appeared as another version of the character in Christmas special The Snowmen later that year, before finally being formally introduced as the “real” version of Clara in the second half of the series with The Bells of Saint John. While she shared wonderful chemistry with Smith, the mystery of Clara's identity overshadowed her character for her first batch of episodes. It was finally resolved in the season finale, The Name of the Doctor, which also gave viewers one final shock twist: the introduction of a previously unknown incarnation of the Doctor, played by respected thespian John Hurt.

Having inherited the series in the run-up to the fiftieth anniversary and overseen its growth to international success, Moffat worked with the BBC to promote the occasion as a huge event. A feature-length special was concocted, shown simultaneously across the globe and even in cinemas. In the grand tradition of previous anniversary specials in the old days, The Day of the Doctor featured multiple Doctors. While Moffat had planned to include Christopher Eccleston as the ninth Doctor, he declined, forcing a major rethink. Hence, John Hurt as a new version of the character – a one-off celebrity special version. Hurt's incarnation – who refused to even go by the name Doctor – was slotted in between Paul McGann's TV movie version and Eccleston's relaunched hero, and neatly sidestepped the numbering issue the writer had created. Bringing back Tennant as the Tenth Doctor and teaming both versions up with Smith's character, The Day of the Doctor embraced the history of the series right back to its beginnings, but focused on modern mythology, tackling the Time War once and for all and moving events forward. There were also fan-pleasing star turns, including Billie Piper's return, albeit not as Rose, and the surprise cameo of Tom Baker, the most popular Doctor of the original run, in a mysterious new role.

The huge success of Doctor Who in the anniversary year was perhaps the modern series' greatest triumph. It was, however, followed by a slump, perhaps the only way it could go after such heights. Smith bowed out in the following episode The Time of the Doctor, which bookended his time-twisting adventures but failed to satisfyingly answer any questions. He was replaced by Peter Capaldi as the Twelfth Doctor. With Capaldi his mid-fifties, the return to an older actor in the lead provided stark contrast to Smith's youthful adventurer and saw something of a return to the series' routes. Capaldi's Doctor was deliberately abrasive, and to begin with at least, rather hard to like. However, his style and gradual development gained him numerous fans. Coleman continued as Clara through the entirety of seasons eight and nine, allowed more complex emotional storylines now that the mystery of her existence was resolved, developing a remarkable, warm yet spiky relationship with Capaldi's Doctor. She finally bowed out after some powerful storylines which saw the Time Lords return fully and the Doctor face some of his most memorable enemies once more.

Aside from the Daleks, the Doctor's most persistent enemies have been the Cybermen and the Master. The cyborg monsters returned to face Tennant's Doctor in the second season, going on to face him and his successors over the following years, while the Master was kept for the finale of series three. The Doctor's opposite number, the villainous Time Lord was played briefly by Sir Derek Jacobi before regenerating into John Simm, whose interpretation was more like a hyperactive child than a criminal mastermind. His next appearance in the two-part The End of Time spelled the end for Tennant's Doctor. For the finale of series eight, the two-part Dark Water/Death in Heaven, both the Cybermen and the Master returned again. Only this time, a further regeneration had turned the Master into the Mistress. Missy, as she prefers to be called, was played as joyfully evil by Michelle Gomez. She would continue to appear throughout Capaldi's tenure, becoming an essential feature of his era.

After a second year off, series ten was deliberately styled as a break from the increasingly involved and backwards-looking stories that had preceded it. A new companion was introduced – Bill Potts, a young woman who was more the Doctor's student than partner, was designed with modern sensibilities and representation in mind. Played by Pearl Mackie, Bill was a woman of colour, openly gay, definitely not posh and a breath of fresh air. The Doctor and Bill were sometimes accompanied by Nardole, the Doctor's new guardian/butler, played by comic actor Matt Lucas. Like Catherine Tate, he had been designed as a one-off comic relief character for a Christmas special, before being promoted to a regular after considerable retooling. Even more surprising was Missy, revealed gradually as being the subject of a rehabilitation programme by the Doctor. While series ten did feature some old monsters, it was mostly fresh, until the two-part finale. World Enough and Time saw the Cybermen return once again, in an origin story that called back to their first appearance in 1966; a request by Capaldi himself, whose fan credentials put even David Tennant to shame. As if that weren't enough, John Simm returned as the Master – rather more restrained this time – to join forces with his own female future self.

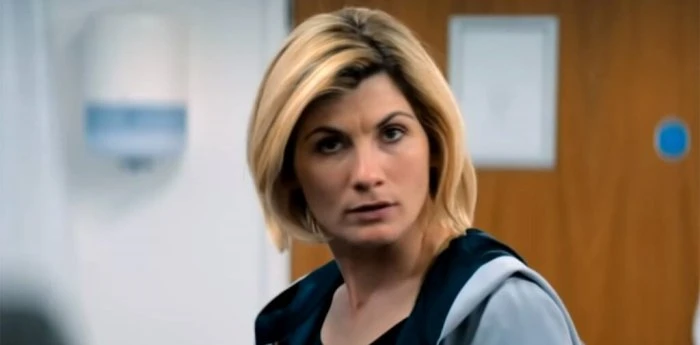

The finale was a tour de force, a grand final story from Moffat, who after eight years was more than ready to move on. However, his replacement, Chris Chibnall, wasn't yet free of his own commitments. Rather than leave the series without its now-traditional Christmas episode, Moffat penned Twice Upon a Time, a final story to see out Bill and the twelfth Doctor, and brought it all full circle by bringing back the First Doctor, now played by David Bradley. This meeting of two grumpy, white-haired old Time Lords seemed a very deliberate choice to contrast with the immediate future. In the end, Capaldi gave a grand farewell speech and the Twelfth Doctor regenerated into the Thirteenth – played by Jodie Whittaker, the first woman to lead the series.

In 2018 the eleventh series aired, under the aegis of Chris Chibnall. Although he had written scripts both for Davies and Moffat, they were never among the best regarded episodes (although series seven's Dinosaurs on a Spaceship was a lot of fun). Chibnall has, however, a strong track record as showrunner on the very successful Broadchurch and also oversaw Torchwood in its first two seasons. Under Chibnall, Doctor Who has entered its third distinct phase of the modern era. After a return to London and briefly Bristol as primary settings under latter-day Moffat, Chibnall's 21st century base for the series is the industrial vistas of Sheffield. His version of the programme is very deliberately diverse and representative. Whittaker played the Doctor as forthright and fun-loving, striving for fair play and vocally non-violent. Her three-strong team of companions (a return to the larger teams of the sixties and early eighties version of the series) was made up of ordinary people enjoying the wonder of the universe. Bradley Walsh plays Graham, a salt-of-the-earth type of bloke, while Tosin Cole plays his step-grandson Ryan and Mandip Gill former police officer Yasmin Khan. With a female Doctor, an older white male companion and two young companions of colour, it's a diverse line-up. In line with this, Chibnall made efforts to include new writers for the series, particularly writers of colour, bringing new perspectives to the show. Episodes include the acclaimed Rosa, in which the travellers meet Rosa Parks, and Demons of the Punjab, set on the India-Pakistan border at the time of the Partition. While as bringing non-white history to the fore is new, the return to a more educational style of storytelling, while embracing a mix of genres, harked back to the very earliest days of the series in the 1960s.

After a very successful start, with viewing figures higher than the series had managed in years, viewership began to drop as the Chibnall/Whittaker era continued. Part of this was down to changing viewer habits over the years, with broadcast television in general losing overnight viewers. While Doctor Who remains one of the most streamed programmes on iPlayer, it's inarguable that its audience size waned towards the end of Whittaker's tenure. While some of this is down to an increasingly sporadic production schedule, Chibnall's reign as showrunner lost fans due to a combination of lacklustre scripts and controversial story decisions.

One thing he can't be accused of is being scared to put his own stamp on the series. While the New Year's Day specials relied largely on rematches with the Daleks each year, the main series took big risks, rewriting Doctor Who's backstory. The twelfth series not only brought in a maniacal new Master, played with relish by Sacha Dhawan, but also revealed another incarnation of the Doctor. The episode Fugitive of the Judoon began by bringing back a memorable monster and John Barrowman as Captain Jack ten years since he was last on the programme. All this served to divert attention from the real twist: a new Doctor, played with swagger by Jo Martin. Not only was Martin the first actor of colour to play the Doctor on the programme, her Doctor explicitly doesn't fit into the run of regenerations that began with William Hartnell.

Chibnall went even further with a storyline that combined retro elements and huge changes to status quo. The Cybermen returned again while the Master revealed the true history of the Time Lords: that it began with the so-called Timeless Child, an orphaned alien with the power to regenerate, who would grow up to be the Doctor we know. Revealing that the Doctor was not only the key to the Time Lords' regenerative powers, but also that she had lives an untold number of lives before the ones we know, was too much for some fans. Arguably, though, it provided Doctor Who with a much-needed sense of shock and mystery: for the first time in years, there was a real sense that anything could happen now.

The sluggish production schedule was dealt an almost fatal blow by the Covid-19 pandemic, with the difficult practicalities of making Doctor Who almost leading to the thirteenth series being scrapped altogether. Chibnall reworked the in-process scripts into a new, six-part story entitled Flux which aired in 2021. Even more expansive in its revelations of the Doctor's past and its near destruction of their universe, it boasted some impressive elements but was overall messy and incoherent. Nonetheless, Chibnall is to be admired for getting it made at all, even if the whole was somehow less than the sum of its parts. Having both agreed to do three series, both Chibnall and Whittaker hung on for a trilogy of specials in 2022, ending with The Power of the Doctor, officially marking the BBC's centennial anniversary. Bringing back Sophie Aldred and Janet Fielding as eighties companions Ace and Tegan, the special also found a clever way to include as many Doctors as possible. Peter Davison, Colin Baker, Sylvester McCoy and Paul McGann all appeared as apparitions of their Doctors, with David Bradley once again standing in for Hartnell.

There was a chance that this would be it for Doctor Who, at least for a time, with the possibility that The Power of the Doctor would become a de facto sixtieth anniversary story. In a surprise move, Russell T. Davies declared his wish to return to the programme after a break of over twelve years. Not only that, but Tennant and Tate returned with him as the Doctor and Donna. While the young, upcoming star Ncuti Gatwa was announced as the next Doctor to great fanfare, The Power of the Doctor ended with a shock regeneration of Whittaker into Tennant, the Doctor mysteriously returning to an old face.

2023 marked Doctor Who's sixtieth anniversary and, after the longest break since the programme's 2005 return, another trilogy of specials arrived. The latest version of Doctor Who is co-produced by Bad Wolf, a production company founded by former BBC executives Julie Gardner and Jane Tranter, both of whom had been instrumental in the 2005 revival. With Davies back as showrunner and chief writer, and familiar faces in front of and behind the camera, it's clear that the decision was made to put the programme back in safe hands for a revamp. However, in spite of peppering the specials with classic characters and bringing back perhaps the single most popular Doctor-companion team of the modern era, Davies did anything but play it safe with the anniversary specials. The three stories were loud, confident and aggressively progressive and diverse.

Unfortunately, anything that is explicitly inclusive threatens a backlash. Davies seemed to fair quite well against this in his original run, but even he was accused of having a “gay agenda” for including queer characters, even though there were far more of them under Moffat's reign. Gay, black companion Bill had her own undeserved share of bigoted criticism, while the gender change for the Master had some fans in fits. The subsequent change of sex for the Doctor, combined with a deliberately mixed race cast, led to anger from the more close-minded fans, exacerbated when the chemistry between Whittaker and Gill led to a gentle romance between the Doctor and Yaz. Loud voices online hoped that, in opposition to all evidence from his past work, Davies would return to make Doctor Who less woke. Instead, his first episode hinged on the identity of Donna's transgender daughter Rose (played by Yasmin Finney and named after Billie Piper's character), while Ruth Madely's character Shirley later celebrated the addition of a wheelchair ramp to the TARDIS.

Davies was no doubt aware that these inclusions would stir controversy, and didn't stop there. Each showrunner has made bigger and bolder changes to the programme's mythology, and Davies made efforts to outdo it all with the Doctor's bizarre “bi-generation” in the third special The Giggle. Unlike previous regenerations which saw the Doctor change appearance, this time he split in two, with Tennant's Doctor continuing to live on Earth while Gatwa's new incarnation ran off into time and space. While this, along with Tennant's return in the first place, arguably undermines Gatwa's introduction, he immediately stole the show. The anniversary year, with Davies back in the driving seat, saw Doctor Who's long history being proudly celebrated. While it wasn't the phenomenon of the fiftieth, the sixtieth saw almost the entire back catalogue of the programme made available on iPlayer. Meanwhile, Disney secured the international streaming rights for the specials and upcoming series, injecting a great deal of extra money into the production.

2023 ended with the first Christmas special in six years, The Church on Ruby Road, allowing Gatwa a proper debut story and also introducing his new companion, Ruby, played by Millie Gibson. This was followed by a full series of eight episodes in May 2024 – launched as a brand new “Season One,” although time will tell if that catches on or reverts to Series 14 in future listings. Gatwa's Fifteenth Doctor is magnetic and charismatic, and, surprising some viewers, Davies has embraced the Chibnall's revised backstory for the character. The Doctor bonds with Ruby over their shared status as foundlings, and much of the new season is dedicated to the mystery of Ruby's origins.

The new season impresses with its production values and the variety of different genres and storytelling styles it utilises in its short run. The haunting 73 Yards, the intense and minimalist Boom, the bitingly satirical Dot and Bubble and the flamboyant Rogue have all received both acclaim and harsh critique. It's been one of Doctor Who's most divisive seasons, but there's been an episode for almost every taste. On the other hand, with mystery piled on mystery, with seemingly little thought as to how they will resolve beyond the “gosh wow” factor of successive reveals, the season holds together poorly as a whole. The lack of availability of its leading man, still busy with the final season of Sex Education as filming commenced, hurts the series as well, although Gibson is more than strong enough to carry the show herself.

2024 will see another Christmas special, guest-starring Nicola Coughlan of Derry Girls and Bridgerton fame, with a further series already filmed for 2025. The latest reinvention of the show has been divisive; with the Doctor now a black, queer, flamboyant orphan, there are inevitably some viewers who are very unhappy, but others have enthusiastically embraced the new direction. After strong viewing figures for the 2023 specials, the latest season achieved surprisingly poor results, not all of which can be blamed on the changing viewing habits of the public. Nonetheless, the series has done remarkably well with the under-16 and 16-34 demographics, considered the most difficult to maintain as an audience. Whatever its future, Doctor Who is sure to keep changing into new and unexpected forms – just like the Doctor.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on January 25th, 2024. Review: Daniel Tessier 2019 and 2024.