Chocky

1984 - United KingdomMatthew Gore is an unusually intelligent and sensitive boy who is selected by a mysterious extra-terrestrial presence as a conduit for information about human life. As this unseen visitor – calling itself Chocky – begins to educate Matthew, his schoolwork and artistic abilities improve at an alarming rate. What starts as a private, almost intimate relationship soon attracts attention, and Matthew finds himself under scrutiny from powerful adults who sense that the knowledge passing through him could be exploited for influence, wealth or control.

The path to bringing Chocky to television was a long one. Pamela Lonsdale, an executive producer at Thames Television, had pursued the rights to John Wyndham’s 1968 novel for more than a decade, only to find them repeatedly tied up with American interests. Progress finally came in 1983 when Lloyd Shirley, Thames’ head of drama, forwarded her a proposal after the rights had been secured by Richard Bates, son of H E Bates. Bates commissioned Anthony Read to adapt the novel, reshaping it into a six-part, half-hour-episode serial. The project moved swiftly once green-lit; Bates soon departed to work on The Tripods at the BBC, leaving Lonsdale to appoint Vic Hughes as producer. Hughes also directed half of the episodes, with the remainder handled by Christopher Hodson in his first children’s drama credit. Casting proved inspired: James Hazeldine and Carol Drinkwater brought credibility to Matthew’s parents, while newcomer Andrew Ellams, discovered almost by chance, anchored the series as Matthew. Glynis Brooks supplied the cool, disembodied voice of Chocky itself.

Chocky remains one of the most thoughtful and quietly unsettling pieces of children’s drama produced for British television in the 1980s. Adapting Wyndham’s novel, the serial resists spectacle in favour of ideas, trusting its young audience with complex themes about knowledge, power and moral responsibility.

What distinguishes the television version is its shift in perspective. By placing viewers firmly alongside Matthew, the series removes the novel’s ambiguity and instead explores the consequences of certainty: we know Chocky exists, and so the tension lies not in doubt but in how adults respond to that truth. This choice suits the medium well, allowing visual storytelling to carry the weight of the concept, from the striking early imagery to smaller, telling moments where Matthew’s sudden brilliance unsettles those around him.

Anthony Read’s scripts are measured and intelligent, occasionally leaning heavily on parental discussion but never talking down to the audience. The philosophical questions posed by Chocky feel genuinely challenging, particularly in the context of a society eager to exploit new ideas for profit or military advantage. The mid-1980s setting subtly modernises Wyndham’s concerns, grounding them in a recognisable world of emerging technology and middle-class respectability.

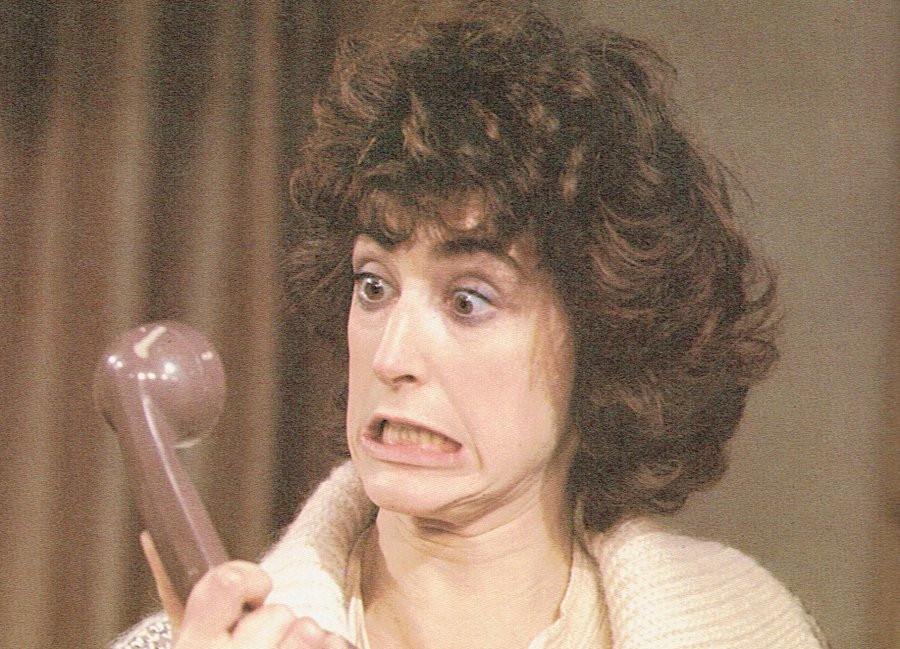

Performances are uniformly strong. Hazeldine brings credibility and emotional depth to a father torn between protection and fear, while Drinkwater adds warmth and unease as Matthew’s mother. Ellams is particularly effective, conveying both vulnerability and an uncanny detachment without ever losing the character’s essential humanity. The decision to keep Chocky largely disembodied ensures the alien presence remains unsettling rather than whimsical.

Visually, the production is restrained but effective, relying on atmosphere rather than effects. The electronic theme and sparse incidental music enhance the sense of something quietly intrusive, an intelligence observing rather than invading. This understatement arguably gives the series greater longevity than many of its more flamboyant contemporaries.

The John Wyndham Estate were so impressed that they approved two further, original sequels scripted by Read. Both were solid entertainment, shifting slightly towards action while revisiting familiar themes. In Chocky’s Children (1985), Matthew encounters fellow prodigy Albertine Meyer, newly arrived at Cambridge on a science scholarship, only for their work to attract the attention of the sinister American industrialist Dr Deacon. Chocky’s Challenge (1986) widens the canvas further, following gifted children around the world as their research into anti-gravity draws military interest. Neither sequel quite matches the quiet power of the original, but together they cement Chocky’s place as one of the most ambitious strands of British children’s science fiction television.

The success of Chocky lies in its confidence: confidence in its source material, in its audience, and in the power of ideas over action. While the later sequels broaden the scope and raise the stakes, it is the original serial that resonates most strongly, capturing a rare balance between children’s drama and adult science fiction. Decades on, it still feels intelligent, unsettling and remarkably respectful of young viewers.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on January 14th, 2026. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.