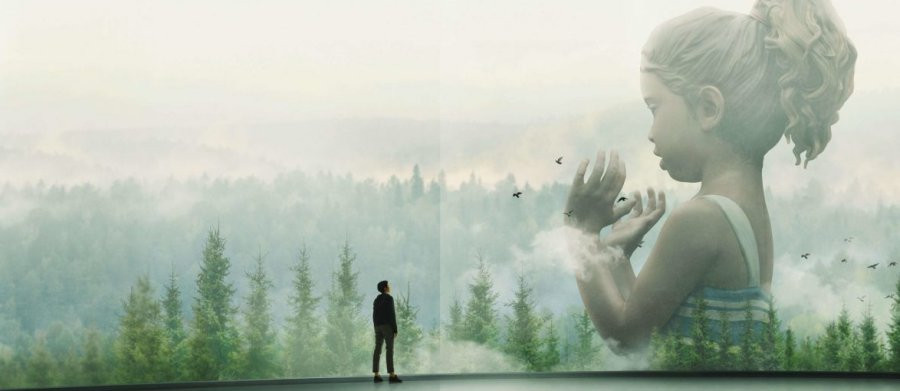

DEVS

2020 - United StatesReview: John Winterson Richards

It is not essential to have a working knowledge of quantum physics to appreciate 'DEVS' - but it helps.

Here is what you need to know. For about two hundred years after Sir Isaac Newton discovered the basic laws of physics, a "deterministic" view of the Universe prevailed. Everything was caused by what went before, so a Frenchman named Laplace postulated that if you knew the position and movement of every particle in the Universe, you could project backwards to all their past positions and forwards to all their future positions. One could therefore "see" both the past and the future. Everything was predetermined and could be predicted. Napoleon, who liked this orderly way of looking at the Universe, made Laplace a Count.

Subsequent physicists found that things are not quite so neat. It turns out that basic particles are odd. You can find their position or their movement but not both. So along came quantum physics, Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle, and Schrodinger's (theoretical) cat being both dead and alive at the same time. Einstein, whose work contributed to this untidy state of affairs but who disliked it intensely, protested "God does not play dice with the Universe." To this Stephen Hawking responded later that not only does God play dice, but He sometimes throws them where they cannot be seen.

Many cosmologists share Einstein's distaste for the rather confusing - and, in some ways, unlikely - picture of the Universe which science now presents to us. As a result, that old science fiction cliché, that there are many, perhaps infinite other Universes offering variations on our own, has become strangely respectable in modern physics. This theory is, however, very controversial, because it generates more problems than it offers to solve.

DEVS is an elite research and development department operating autonomously within a fictional quantum computer corporation, Amaya, which seems to be based loosely on Google. It was founded on the assumption that the Universe is deterministic, in spite of quantum physics, and therefore seeks to develop technology that can "see" both the past and the future. This would obviously be of less value if there were many Universes, because that would mean that anything might be possible. If, however, the technology could be restricted to this Universe, there is no need for the script to elaborate on its immense commercial possibilities, or its potential significance for national security: the interest of the State is represented by a sinister Senator - US Senators are always sinister in these sort of conspiracy thrillers.

Yet the twist is that the real reason Forest, the eccentric founder of the corporation, wants to develop it is neither commercial nor political: it is very, very personal to him.

When a suspiciously charming Russian goes missing after his first day at DEVS, his girlfriend, Lily (Sonoya Mizuno) wants to find out what happened. She becomes increasingly suspicious of what she is told. At this point, we think we know where we are - in a standard corporate conspiracy.

This is where 'DEVS' begins to get very clever. At first, the company seems very supportive and co-operative. Of course, we know from similar stories that this is only an act and that they are hiding something. In fact, we have already seen that the second part of that is true. However, we do not get the expected evil corporation. Although Forest is capable of ruthlessness, he is basically a good man doing bad things for a what he thinks is a good reason. His initial show of concern for Lily is by no means insincere. He is a genuinely compassionate employer.

Forest is played with great nuance by Nick Offerman, who established himself as the master of subtle understatement as Ron Swanson in the comedy Parks and Recreation. In 'DEVS' he proves he can do the same in drama. On the surface, Forest is as calm and controlled as Swanson, but that hides a more complicated character beneath. Although he is driven by a definite agenda of his own, Forest is also a frightened man who is being forced to come to terms with a total loss of agency. He is vulnerable and sympathetic, not only in spite of his harsh decisions but because of them.

His girlfriend - not that she would use that term - and the chief designer of DEVS, Katie, is a fanatical true believer in the science of what she is doing. She finds herself torn between the consequences of that science and her love - not that she would use that word either - for Forest. She is played by Alison Pill who also excelled recently as a similarly conflicted scientist in Star Trek: Picard. Gradually, she reveals more and more of the humanity of a character who seems at first cold and uncaring. It is ultimately a very poignant performance.

The third outstanding performance comes from Zach Grenier, who was so good as the gambler turned preacher Andy Cramed in Deadwood. He plays Kenton, head of security at Amaya and Forest's evil angel. A past CIA operative, Kenton enjoys his work a bit too much and goes beyond what Forest asks of him. Yet Forest unleashed Kenton in the first place, knowing what he is, and so remains responsible. Kenton therefore takes the reasonable position that he has a right to protect himself. He is not a cardboard villain but a three-dimensional character with an internally logical motivation.

Given that the three main antagonists are so interesting, our protagonist seems rather dull, a standard "strong modern woman" type. Such characters were once brave and compelling, but are now almost mandatory and therefore stereotypical unless something special is brought to the table, which is not the case here. There is in fact something rather unpleasant about how Lily exploits both the expertise and the residual romantic feelings of a past boyfriend, Jamie (Jin Ha), whom she had dumped hard before meeting the Russian. Jamie is likeable but something of a doormat, so he is less sympathetic than pitiable.

Cailee Spaeny and Stephen McKinley Henderson make a fun intergenerational double act as Lyndon and Stewart, programmers at DEVS. Lyndon is a precocious teenager, while Stewart is unusually old for a programmer and seeks to put the science in some sort of broader context. He often serves as the voice of reason. He points out how a generation that knows nothing about history, art, and music knows nothing about politics - "You are not woke, you are comatose." He worries that Forest does not ask him about the poetry he quotes.

Although all the characters who express their views on the subject say they are not religious, it is significant how much religious imagery, allegory, and even music permeate 'DEVS.' Forest has long hair and a beard, and at one point seems to have a halo of artificial lighting about his head. There are frequent allusions to theology in the dialogue, especially from Forest. The DEVS project is essentially an attempt at Omniscience, one of the attributes of Divinity - even if it must fall short of Omnipotence if the deterministic assumptions on which it is based are true.

The whole debate about determinism versus free will at the heart of 'DEVS' is itself only the modern manifestation of a much older theological debate about Predestination. This begs the question whether scientific determinism and theological Predestination might be the same thing, or whether one might not be the instrument of the other. This is Big Issues television on a level rarely seen and all the more welcome for it.

It is therefore ironic that, in the end, it falls down on the science. It was always odd that a quantum computing entrepreneur could ignore a century of quantum physics in his deterministic assumptions. Even if Forest was a bit of a monomaniac, surely his Board of Directors and investors would have something to say about that.

It was also frustrating that no one seems to have thought to put those deterministic assumptions to the test. Surely to know the future is to change it. Forest points out that someone only needs to put her hands in her pockets rather than fold her arms to alter what is predicted, but no one thinks to try it.

Finally 'DEVS' makes the common science fiction mistake of assuming that copying all the information about a person to a computer, which may be theoretically possible, is the same as uploading their consciousness, which it is probably not.

In most shows, these would be minor quibbles but 'DEVS' is principally a Drama of Thought. The technology is not a McGuffin to further the plot but the whole point. The conspiracy thriller aspect is soon left far behind. Indeed, the conspiracy seems to consist of only three people, Forest, Katie, and Kenton, plus some minions. Some unusually benevolent Russian spies turn up but then seem to lose interest in the biggest prize in the history of secret intelligence.

One suspects that, once the salaries of the three established actors were deducted, 'DEVS' was produced fairly cheaply. There are some street scenes in San Francisco, the campus of the University of California at Santa Cruz stands in convincingly for the corporate headquarters of a major Silicon Valley enterprise, and the Cathedral-like 'DEVS' laboratory set is a masterpiece, but the cast is small, much is done with CGI, and the action is low key. No matter. The real drama in 'DEVS' is the human interaction and the battle of ideas. As such, it is a refreshing change from most recent television, even if it is not quite as clever as it thinks.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on September 11th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.