Neverwhere

1996 - United KingdomThe adaptations of Neil Gaiman's Good Omens and American Gods for significant televisual events; high budget landmark series of works by a superstar author.

Rewind twenty-odd years to 1996, and it was a very different scenario.

Gaiman was, while a respected figure emerging in the fantasy scene, hardly a household name. Then, Gaiman was known mostly for his work in comics, a format far less well regarded than it is today, and while Good Omens had been published six years earlier, it was Pratchett who remained the big name on the cover. It wouldn't really be until the publication of American Gods in 2001 that Gaiman would achieve real cross-Atlantic fame.

No, it was Lenny Henry's name that carried the weight necessary for the BBC to greenlight Neverwhere. Even at the time, Henry's name was associated primarily with comedy, but nonetheless, it was he who had the initial idea for a series that revolved around a society of homeless people in London. Gaiman was more reluctant, fearing that that a bunch of homeless tribes having adventures would glamorise homelessness. It's a reasonable concern, but one that the pair combated by upping the fantasy elements of the story, pulling it further from reality.

Neverwhere materialised as a serial broadcast in six half-hour episodes in the autumn of 1996, precisely the right time of year for a dark, unsettling tale about people out in the cold. Directed by Dewi Humphreys, it starred Gary Bakewell as Richard Mayhew, an ineffectual Scottish office worker living in London, and Laura Fraser as Door, a young gothy sort who Richard finds bleeding in the street. Taking pity on her and taking her in to tend her wounds (she insists on not going to hospital), Richard finds his life changed irrevocably. Door recovers quickly, but Richard is now a part of her world, and the rules of his life change completely. People no longer seem to see or hear him; his dreadful fiancé and his cocky best mate have forgotten who he is, his desk has been cleared out and potential buyers are viewing his flat.

It's an ingenious premise that cuts to the very heart of the plight of the homeless. Even the best of us must admit that we've turned a blind eye to someone in need, walked straight on past that person living on the street and pretended not to hear their cry for help. As Door puts it, it's less that people can't see him as they don't notice him, but it's an aggressive, determined sort of refusal to notice. Door takes Richard to the world of London Below, a realm that exists beneath, around and conterminous with the London Richard knows, the so-called London Above. London Below is hidden in alleyways, disused tube stations, sewers and rooftops, all around London Above but rarely interacting with it. Homeless people, of the sort you might walk past every day, are positioned as partly of London Above – enough to get the odd scrap of charity – but primarily of London Below. It is a community of people that have been abandoned by the upper world, and their descendants.

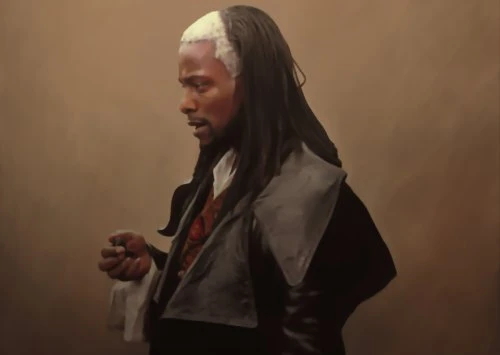

The depiction of this world is as good an example of urban fantasy and magic realism as any you might find, before these terms became popular in literary circles. London Below operates by a kind of feudal system, with baronies and fiefdoms. Door is herself the sole remaining member of a noble house, investigating the murder of her parents and sister, and herself has the magical ability to open anything (hence her name). This is both a clever method the advance the plot, and a tremendously dangerous weapon when she has call to use it. She calls on the assistance of the Marquis de Carabas, inspired by the Puss in Boots character of the same name. Played by Paterson Joseph, the Marquis is an untrustworthy trickster with a broad grin, swaggering about the place in Georgian finery and an opulent leather coat. They are joined by Hunter, a legendary warrior who acts as their bodyguard, played by Tanya Moodie as a sort of African war queen, on her own mission to hunt the legendary Beast of London.

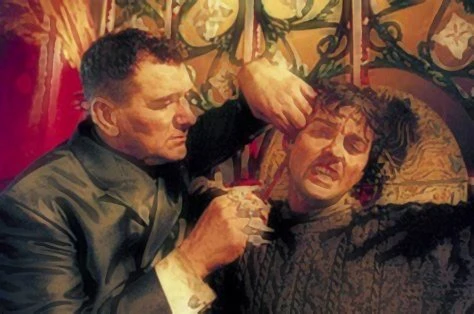

There are villains, of course, in the form of the loathsome, conniving Mr. Croup and the violent slab of muscle Mr. Vandemar, played by Hywel Bennett and Clive Russell respectively. These vicious creatures kill for fun and profit, and dog the heroes throughout their journey through London Below. Beyond these central characters are all manner of odd beings, from the Ratspeakers who keep the counsel of the rodentine inhabitants of the city, to the Velvets, vampire-like creatures who prey on the unwitting (look out for an early appearance by Tamsin Greig as one of their number, the slinky Lamia).

Much of the inspiration for the characters and locations in Neverwhere are atrocious, London Underground-themed puns, and you can imagine Gaiman and Henry giggling to each other as they came up with them. Knightsbridge is a literal bridge, that takes its toll on the human souls that cross it. The Earl's Court is at odds with rival power Baron's Court, and ruled by the senile Earl (the late, great Freddie Jones). The Black Friars guard holy relics, Hammer Smith is a blacksmith and the plot hinges on the plans of the Angel, Islington – a genuine angel who fell from Heaven, played with ethereal poise by Peter Capaldi. Not everything is Underground-related – there are characters named Serpentine and Old Bailey – but nonetheless, the absence of the Elephant and Castle as a mythical pairing seems odd.

Much of the appeal of Neverwhere is in these gleefully silly concepts, played straight but with a knowing wink. It's the wit of the script that makes it work. There are some design triumphs as well; the opening titles by Gaiman's long-time collaborator Dave McKean, combined with Brian Eno's haunting score, are unsettling. Other than this, though, Neverwhere's weakest elements are its visuals. The visuals are tremendously nineties, particularly the Floating Market scenes with its odd mixture of rave culture and pseudo-historical costuming, and the opening monologues for each episode, which involve main characters speaking over jumping still images of themselves, something which probably seemed very cool and interesting at the time but which look horrible naff now.

More obviously, the quality of the footage itself is poor. It was originally planned that the series would be filmed on video before being treated in post-production to provide a filmic look, a common process today but fairly unusual at the time. As such, it was recorded on overlit sets to allow for the eventual darkening that the filmic treatment would provide. Unfortunately, this idea was later dropped for budgetary reasons, meaning that the gothic underworld is grossly over-illuminated, and the untreated videotape looks garish and cheap. This wasn't quite as bad when it was released on VHS, due to the rapid deterioration in quality that home video often experienced, but on DVD the flaws are painfully apparent. This visual cheapness makes it look rather like a low-budget children's series or sitcom, sitting uncomfortably with the content. If anything, it looks rather like the tail-end of Doctor Who's production, which suffered from similar stylistic problems. With Paterson Joseph giving a very Doctor-ish performance as the Marquis, alongside the strange visual elements and the production style, this is basically what Doctor Who would have looked like if it had carried on into the nineties.

The visual letdown of Neverwhere led to a poor reception at the time, but it has become something of a cult favourite. It's certainly a unique series, with some ingenious ideas and clever dialogue. The central performances are mostly excellent. Bakewell's Mayhew is rather pathetic to start with, but develops believably as the adventure continues, and he shares wonderful chemistry with Fraser. Some of the supporting cast are straight out of the children's telly school of acting, and along with the look, it sometimes seems like the series isn't quite sure who its intended audience is. Yet there's a real sense of unease watching the series for the first time, a sense of never knowing quite what strange event or environment will come next.

Dated and peculiar as it is, Neverwhere isn't quite like anything else on television.

Dan Tessier's web page can be here: Immaterial

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on November 10th, 2019. Written by Daniel Tessier for Television Heaven.