The Deal

2003 - United KingdomReview by John Winterson Richards

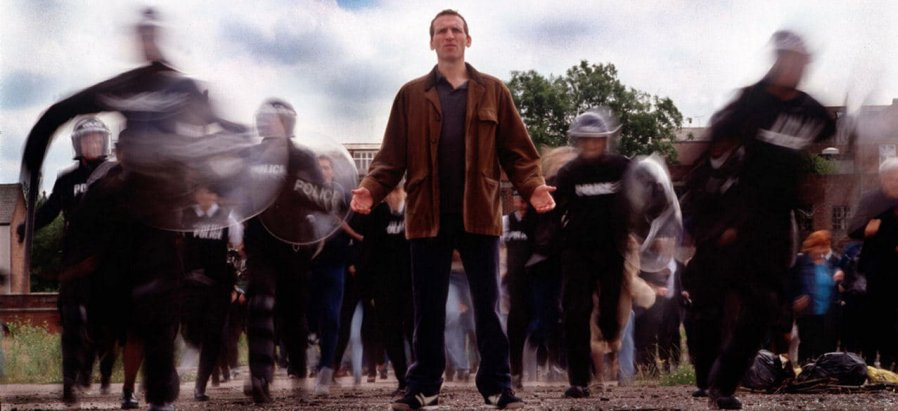

A 2003 television film written by Peter Morgan, directed by Stephen Frears, and with Michael Sheen as Mr Blair, The Deal is the first of an unofficial "Blair Trilogy" about the then Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The triumvirate reunited for a commercially very successful feature film The Queen (2006), and Morgan and Sheen later went back to television with The Special Relationship (2010).

The Trilogy as a whole raises important questions about the theory, practice, and ethics of writing fiction about people who are not only still alive but active in public affairs. The Deal took a definite position on questions of fact that were disputed and of great political significance at the time.

The eponymous deal was allegedly made between two leading Labour MPs in 1994. Labour was then out of power but looked almost certain to win office at the next General Election. With the wonderful benefit of hindsight, knowing now that the 1997 Election was a Labour landslide, it is tempting to view it as even more certain than it was, but their unexpected defeat in 1992 had a profound impact on the psychology of Labour activists at the time as The Deal makes very clear. It was ultimately the main reason why the more pragmatic and centrist Mr Blair emerged as leader rather than the traditionalist Gordon Brown, who was closer to the heart of his Party and who had long been considered the natural successor to the respected John Smith, the leader who had just died.

At almost any other time Mr Brown, a prominent figure in Scottish politics since his student days, would have filled the vacancy with little serious opposition, but in 1994 the priority was to avoid anything that might throw away another General Election. Influential people within the Party, including past leader Neil Kinnock and his clever former spin doctor Peter Mandelson, saw the more media-friendly Blair as their Party's best hope of guaranteeing victory.

Sensing his natural supporters slipping away to Blair, and perhaps feeling a little betrayed, Brown decided not to stand for the leadership. For many years it was denied that there had been a formal deal struck at the trendy Granita restaurant or anywhere else, but there was obviously some sort of understanding. The nature of that understanding has been the subject of a great deal of speculation ever since, and such speculation is always excellent raw material for drama.

One therefore cannot blame Peter Morgan for taking advantage of the opportunity by writing what he did. The problem is that, such is the power of television, the version broadcast in The Deal became the generally accepted version at a time when it was of the greatest political importance. From what we know twenty years after The Deal was broadcast, and almost thirty after the alleged deal itself, Morgan seems to have got his facts broadly right, but even now there is no absolute certainty and there was no way he could have known at the time. Either way, what he wrote had political consequences in 2003 and beyond.

The generally accepted version is that Brown agreed not to stand and Blair agreed to appoint him Chancellor of the Exchequer with wide powers over all aspects of domestic policy. This is what happened and for ten years Brown was indeed one of the most powerful Chancellors of the Exchequer in British political history. More controversial is the implication that Blair said that he did not intend to go on "too long" like Margaret Thatcher - who was Prime Minister for eleven years - and would resign in Brown's favour after two terms. This does not have a clear meaning as it does in American politics. It could mean two complete Parliaments - up to ten years - or two Parliamentary Elections, in which case it might be expected that Blair might resign at some point in his second Parliament to give his successor the opportunity to fight the election after that on his own manifesto. If that was indeed the understanding, Blair obviously chose to interpret it in the former sense. That the final meeting was so informal and nothing was put in writing was by 2003 seen as typical of Blair's relaxed style of "sofa government," the weaknesses of which were becoming more apparent by that point.

So, irrespective of whether or not it was accurate, The Deal seemed authentic. It was required viewing for the entire political and media class, most of whom knew Morgan had put a great deal of effort into his research and assumed he was privy to things they might not know themselves. From before it was broadcast to the present day, The Deal has therefore been generally viewed more as a dramatised documentary, which it was never intended to be, than as the relationship drama it is.

Mr Brown's many friends in the Labour Party, together with those to the Left of both men who always despised Mr Blair, were encouraged by what they saw in The Deal to press for Brown to hurry up and replace Blair as they thought had been agreed. This deepened divisions in the Party that had been opened up over the Iraq War and which became an important factor in British politics over the next few years. It was, for example, heavily referenced in the satire of The Thick of It. In spite of grumbling within his own Party, Mr Blair did lead it into a third General Election, and subsequently resigned in favour of Mr Brown in 2007. So in the end both men got what they wanted, and what was said to have been agreed. Mr Brown got the job he wanted, but later than he wanted, when the shine was beginning to come off the "New Labour" brand, and while Mr Blair got his ten years, it seems that by that stage he wanted to stay a bit longer. However, the widespread perception established by The Deal was by then so strong that it would have been difficult for him to resist.

A television drama about political events therefore proved to be a considerable political event in its own right. It helped to generate a crisis of legitimacy that was eventually to prove fatal to the career of the most powerful British Prime Minister since Margaret Thatcher.

It is therefore possible to discuss The Deal as politics, as history, and as drama, but this is not the place for political debate and only those directly involved are in a position to comment on its historical accuracy - one suspects their memories might differ.

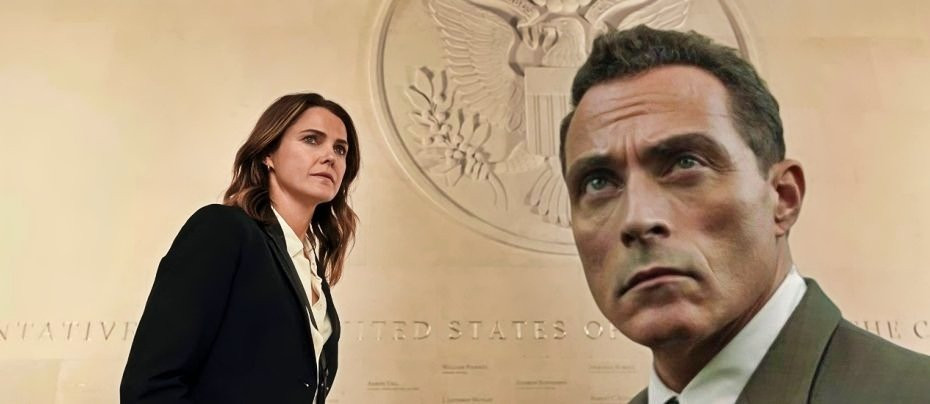

Trying to assess The Deal purely as a dramatic work, it is a compelling relationship piece but lacks substance. If this was about two completely fictional politicians, we might feel we had been given little reason to care much about either of them - so perhaps we cannot separate the drama from the politics and the history after all, because any emotional reaction will depend on how the viewer feels about Mr Blair and Mr Brown - and the big scenes are curiously lacking in punch.

Indeed, it is surprising that Morgan does not make more of what he was given. He mentions Brown's misplaced sense of deference in refraining from campaigning for the leadership between Mr Smith's unexpected death and his funeral but does not go on to illustrate how his chances melted away in those few crucial hours. "Show, don't tell." The scene at Granita - filmed at the actual restaurant shortly before it closed - is a damp squib. It seems like almost an afterthought. While the best evidence we have now confirms that the meeting there was sealing the deal rather than making it, this is one occasion where a little more dramatic licence might have been permissible, even expected. There is never any real clash of ideas or principles between the two men but we seemed to have been building towards a clash of personalities and cultures that is never delivered.

There are some good early scenes evoking the competitive friendship of young men, and if it seems unlikely that Blair and Brown were ever as close or as important to each other as the script implies, that is a necessary dramatic liberty. In general, there is too much "on the nose dialogue" - politicians are masters of not saying what they mean - but a scene with the Scottish Labour MPs boozing on the Friday night train to Edinburgh seems particularly credible, evoking the Old Labour culture of which Brown was a comfortable part. Note that Blair is absent, despite his constituency being on the same line, a subtle indicator that he was never really part of his Party culturally or socially.

Michael Sheen's three performances as Blair defined his career and also how most people probably now remember Mr Blair - as Bambi with the occasional moment of low cunning. Whether or not that is fair or accurate, the image has become the political reality. Again, such is the power of television .

David Morrissey is more sympathetic as Brown, even if he is slightly unfair to him by going the well trodden "dour Scot" route when Mr Brown actually comes across as a very personable individual with a politician's easy charm if you meet him casually. It is in the nature of the news media to base their caricature versions of public figures on what they did on their worst days and Gordon Brown suffered from that more than most. It is a pity that Morgan and Morrissey did not take the opportunity to do more to correct the popular misrepresentation.

Looking back at it after twenty years, one is struck by how it seems devoid of passion. This is a reflection of the politics, or lack of politics, in Britain between the end of the Cold War and the end of the Noughties. There were no great dividing lines between Blair and Brown, or between Labour and the Conservatives come to that. All were offering slight variants on the same basic policies. Nothing is at stake but the ambitions of two ambitious young men.

As a result, The Deal is a rather undramatic political drama, best now viewed as an interesting period piece, the evocation of a particular time, rather than as a record of great events, and as an example of how a television representation of history can itself become a small part of history.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on November 17th, 2023. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.