The Price of a Record

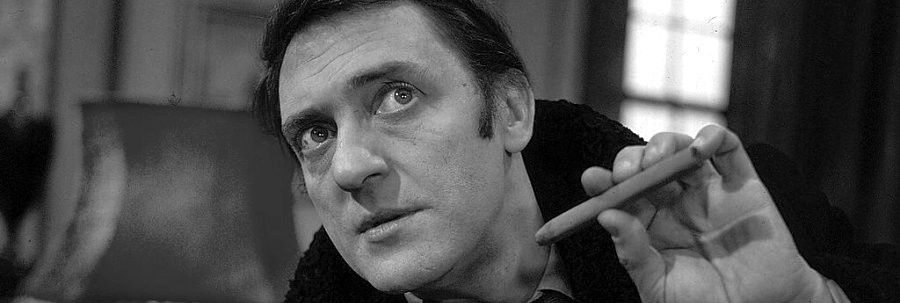

1967 - United Kingdom“Well, it’s the good old days of the Roman arena. The chaps coming down to watch the gladiator...and let’s make no mistake about it…if you’re not prepared to get your nose punched don’t go down into the arena.”

"Why would a man of 45 risk his neck trying to break a world speed record he already holds? Why does he want to drive an 11-year-old boat on a lake at least one mile too short for even marginal safety? I doubt if Donald Campbell really knows the answers." So begins one of the most remarkable documentaries of the 1960s. One that started full of hope but ended in tragedy.

The documentary deals not so much with the question of how Donald Campbell died - but why.

For eleven weeks Donald Campbell tried at Coniston to break his own world water speed record of 286.78 mph. Time and again imperfect weather conditions or frustrating technical trouble, at the Lancashire lake, delayed him. A film unit working for a consortium of four small ITV companies (Border, Westward, Ulster and Grampian) who were backing him financially, began to get impatient. Like Campbell, they expected the attempt to take only three weeks. And the cost of keeping the unit at Coniston had risen enormously. "All we wanted was to film the end of the story - Campbell's success or the final trial of Donald Campbell," said producer Douglas Hurn.

The Price of a Record tells the tragic story of Campbell's last weeks. The programme relates not only the fatal record attempt but delves into Campbell's personal library of film material covering other attempts —including film Campbell shot from the cockpit of his craft - Bluebird.

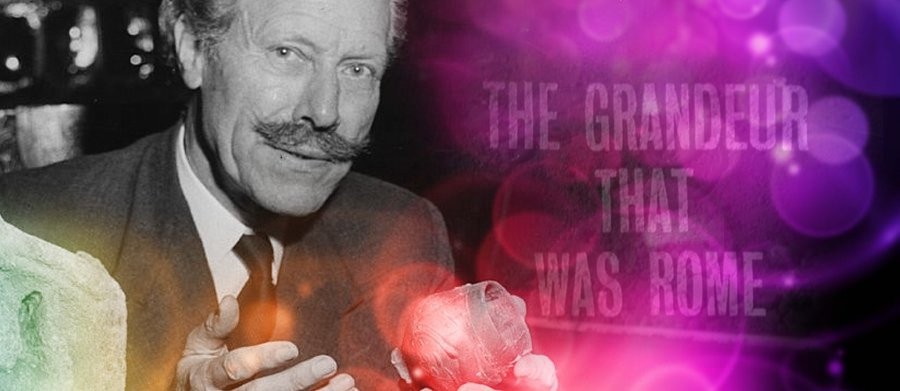

The film begins by looking at clips of Donald's father, Malcolm Campbell, establishing records and receiving public acclaim, and it soon becomes evident to even the casual viewer that Donald lived, certainly in his formative years, very much in his father's shadow. Establishing records and receiving plaudits from all around him, Malcolm became a popular figure at a time between the two World Wars when speed, on land, sea and in the air became the public passion. Malcolm, a wealthy insurance broker, began as a racing driver at Brooklands in the 1920s. He became the first man to travel on land at 150 mph and then built a succession of Bluebird cars, each faster and more powerful than the last. By 1933 he was travelling over land at 272 mph. Captain Campbell became Sir Malcolm and the accolade reflected the enthusiasm of the thirties when heroes were revered much less critically than they are today.

Sir Malcolm was described by those who knew him as unbending, uncompromising, and impossible, a man you either loved or hated, but a man you could never forget. Donald Campbell admitted that his father was "intensely selfish" before further admitting that was one of the traits he'd inherited from him. Caught by the excitement and the public acclaim, Sir Malcolm had little time for family matters, so it's no wonder that Donald grew up with a desire to get closer to his father, whom he saw as a super hero. But initially, Sir Malcolm, concerned for his young son’s safety, didn’t want Donald to have anything to do with racing. It was only after Sir Malcolm’s death that Donald took up the mantle.

Donald’s first attempts at emulating his father’s successes were far from successful. Mechanical failures with a gearbox breaking at 150 mph over water led to near disaster. As a result, the world water speed record went to America. Going back to the drawing board, Bluebird, at a cost which almost broke Donald ("There's no going back in life. If you've started something you've just got to finish it”), was redesigned and eventually he reclaimed that record reaching a speed of 202 mph on Lake Ullswater. Further triumphs and disasters followed. In Utah, an attempt was made to break the land speed record. During the attempt, Bluebird became airborne and crashed at nearly 400 mph. The fastest crash ever recorded on land left Donald Campbell with a fractured skull, a ruptured middle ear and a contusion of the brain. It was only the car's tremendous structural integrity that saved his life. This was 1960 and it would be 1963 before Donald got behind the wheel of Bluebird once again.

All these incidents are recounted by Donald Campbell in the documentary with a surprisingly emotional detachment. But there were further problems. Donald, it seemed, didn't quite catch the public's imagination as earlier pre-war heroes did. The documentary relates how he gradually lost his backers and supporters during an earlier ill-fated land speed record in Australia. What motivated him to continue was unclear although some say it was a mixture of pride and adolescent enthusiasm. "People say I haven't grown up. Well, I'm prepared to admit it," he told the documentary team. "It is a sad day when a man loses the enthusiasm of a schoolboy."

These are the last interviews Campbell gave. To get more of an insight into the man, interviews were conducted with Campbell’s wife, Tonia Bern, chief mechanic Leo Villa and designer Ken Norris. Said producer Hurn: "We have tried to present an impassionate documentary account of the attempt. If Campbell also comes out as a very brave man, then I shall be happy."

One newspaper suggested that Campbell was living in the past. But the apparent lack of interest didn't worry him. "This isn't done for public appeal - this isn't done for public entertainment", he told the documentary interviewer. "If I was putting on a theatrical play and nobody wanted to watch it I'd be very worried. This isn't put on as public entertainment. It's put on to try and reach a certain goal, to see a British bloke first past the magic 300 mark." When pressed on the risk, Campbell replied, “Well, it’s the good old days of the Roman arena. The chaps coming down to watch the gladiator...and let’s make no mistake about it…if you’re not prepared to get your nose punched don’t go down into the arena.”

A few days after this last interview, Donald Campbell went into the arena one last time. Recorded commentaries from Bluebird's cockpit are heard during the craft's final run on Coniston Water right up to the fateful second when Bluebird takes off and does a flip with Campbell's last words being "I'm going!" The crash, recorded by the film crew, was seen on news channels around the world that same night, 4 January 1967.

The documentary, which was made in colour, was shown on ITV (in all regions except London), on Tuesday 6 June 1967 before being shown in more than sixty countries. In the UK it was the eighth most-watched programme for the whole of that month.

In his notes on the film for TV Times, Alan Kennaugh wrote: 'The dream of Donald Campbell, the man who told me he was doing it all for Great Britain, had ended. This was the price of a record.'

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on June 29th, 2023. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.