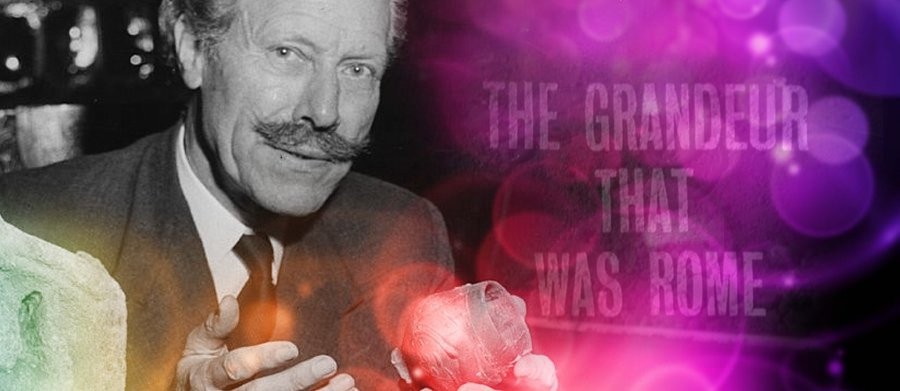

The Grandeur That Was Rome

1960 - United KingdomThe Romans had it right with their fine statues, impressive buildings and straight roads. Here we are, they seem to be saying, and as long as there's civilisation here we'll always be.

What they left behind would lie undisturbed beneath the feet if archaeologists hadn't unearthed it, cleaned it up and explained its meaning.

Programmes on historical digs are a regular feature of the schedules now but, if you have a root around the History section of the BBC iPlayer, you'll find relics of the BBC's 'first steps into archaeology programming.'

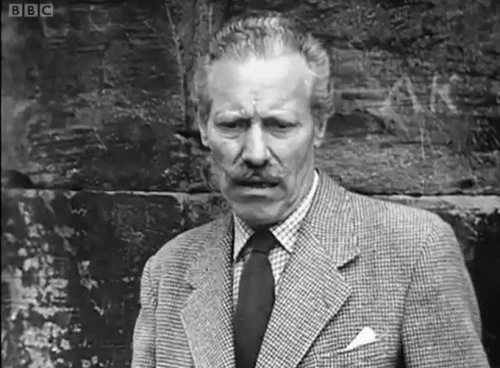

Looming large among the artefacts is Sir Mortimer Wheeler – academic, wartime British army officer and TV Personality of the Year for 1954. I've done a fair amount of research on the subject but I am unable to discover Gilbert Harding's reaction to losing out in the popularity stakes to a fusty old historian.

There's no reason for Gilbert to feel bad, though. Mr Wheeler is an engaging presenter who is able to describe and interpret centuries-old events as if they have just happened.

Mr Wheeler first became known to the viewing public when he appeared in Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? which ran from 1952 to 1958. This was a panel show in which three historians attempt to identify antiquities supplied by various museums. Three episodes are available to view on the iPlayer and they are well worth a watch. Besides the host, Glyn Daniel, Mr Wheeler appears to be an ever-present as the other experts in each show are all different.

At about 9.30ish on consecutive Friday evenings in May 1960, he presented The Grandeur That Was Rome, a series of three 30-minute films dedicated to, well, the grandeur that was Rome.

It was produced and screened before the advent of a second BBC channel, so the broadcaster is given as the BBC Television Service. Today it would probably start out on BBC2 before being re-located to the channel's slightly more high-brow cousin BBC4 for the repeats. It's a shame BBC4 ditched the 'everyone needs a place to think' slogan as I thought it was an apt and pithy way to describe its output.

Although it is billed as an archaeology programme, Mr Wheeler doesn't do any digging. It is more in the style of a standard history show as the learned professor sucks on his pipe and expounds on the skeleton of an empire, gods and men, and Roman art and architecture.

He is not bound to the studio but he must be absolutely sweltering because he flits from sunny Rome to the sultry south of France wearing a suit and tie, as if on a Monday morning trek through a pea-souper to a draughty office in London. Mr Wheeler operated in a time when a hospital doctor would have been a man in a long white coat, a worker in the City would have been a man in a bowler hat and a TV expert would have been a man in a heavy woollen suit. To sort of quote from Philip Larkin, women began in 1963.

Mr Wheeler would have looked much more dashing and at ease in a safari suit, topped off with a fetching pith helmet, but perhaps he thought that to dress in so casual a manner would only divest him of his archaeological super powers. Clothes maketh man or, as the learned lad himself would have said without having to look it up beforehand, vestis virum facit.

The impressive thing about Mr Wheeler is the confidence with which he delivers his material. He makes it looks as though he's saying it off the top of his head but the credits show Stephen Hearst as being responsible for the script.

I think it must be all that wartime Army officer training, combined with his impressive moustache, that makes Mr Wheeler so commanding a presence. He expects his, or Stephen Hearst's, words to be believed and obeyed. If he were to break off from a discourse on the temple of Mithras to demand that the viewer make him a nice cup of tea, the viewer would salute, unbox the best china and ask Lieutenant-Colonel Wheeler if he takes milk and sugar. Well I would anyway.

It must have been a liberating experience for the viewer to end the working week in the sunny climes of Nimes or Leptis Magna with a knowledgeable gent as a tour guide. Liberating but also frustrating because of the monochrome. All that blue sky and sun negated by all that black and white.

The viewer could watch a documentary series such as Look at Life in glorious Technicolor but would have to go to the pictures for the privilege. Sartre almost had it right when he said that hell is other people. He should have said that hell is other people coughing and sneezing and otherwise disturbing the peace of the two and nines while you're trying to enjoy a film that you've paid good money to watch. When faced with this prospect, I think I'd have stuck with black and white in the comfort of my own home.

It's strange to watch a history programme that isn't a series of talking heads, each vying for the viewer's attention. An exchange of ideas between enlightened adults is undoubtedly a good thing but sometimes I just want to watch an old bloke sweating profusely and explaining that Rome expanded 'as the trees grow or the sun shines - through a sort of obscure inevitability'. The vagueness of this premise would probably not withstand the scrutiny of Mary Beard or, come to that, a relatively clued-up GCSE student, but it's one man's view and he's entitled to it.

The programme benefits from an epic musical landscape to go with the drama of the piece. Pictures of a mosaic depicting combat and slaughter are accompanied by the sounds of a surging orchestra in full flow. As a contrast, beautiful aerial shots of the port of Ostia are kept company by an air from those parts of the orchestra charged with supplying gentle and serene music. It's a simple trick but, as here, the perfect mix of sound and vision can produce wonderful and memorable effects.

This being stuffy old 1960, the programme's title is taken from a literary source, in this instance a poem 'To Helen' by Edgar Allan Poe. The poem is set in days of yore so Poe throws in a reference to 'the glory that was Greece, and the grandeur that was Rome'.

In the early 2000s, Adam Hart-Davis did a show on the Romans in Britain called What the Romans Did For Us. This is a good choice for a title on the not unreasonable grounds that more viewers would be aware of a Monty Python reference than a quotation from a 19th century poem.

For those enthralled by the glory that was Greece, in 1958 Mr Wheeler hopped aboard ship with the Hellenic Travellers Club for his Armchair Voyage – Hellenic Cruise. He is joined by other academics such as John Wolfenden, Michael Maclagan and Lord Stanford as they stop off at ancient ports in the Eastern Mediterranean and give lectures to the Travellers Club on board ship. I assume this Club consisted of those members of the public who were willing to pay for the privilege of being lectured at in the middle of the Med. If you've got the time, the money and the inclination, why not?

If the Romans and Greeks are too ancient for your tastes, consider Mr Wolfenden and his relevance to the here and now. He was chairman of the committee that recommended the legalisation of homosexuality and the report of this recommendation bears his name. Emperor Hadrian, among others, would have applauded. Not that Hadrian would have been too concerned by the long arm of the law. What's the use of being an emperor if you can't do what the hell you like? It's a stressful job and you accept its compensations in any way that suits.

Mr Wheeler greets his nominal equals, his fellow professors, by their last names only – 'Maclagan!', 'Stanford!' so I dread to think how he addresses the underlings behind the camera. The usage may or may not be a remnant of his schooling, but it reminds me of the Tomkinson's Schooldays episode of Ripping Yarns in which even Tomkinson's mother calls him Tomkinson.

I don't know how Mr Wheeler liked to be addressed but I'd be willing to bet that no-one had the nerve to call him Morty.

With Stanford! and Maclagan! he gets into an intense discussion on Agamemnon and the fall of Troy. Wheeler! wisely sits between the other two in case it gets too heated. The disinterested observer may wonder why educated adults get so fired up over events that may never have happened and characters that may never have existed. Does it matter? I suppose it matters to academics because their reputations and livelihoods depend on it.

The Hellenic Cruise is also available for viewing on the iPlayer. I don't find it as enthralling as the programme on Rome because I've always been more enthralled by the Romans than the Greeks. I think it must be something to with the fact that the Romans actually lived among us, bringing law, order and the civil service with them.

I made my own trip to the remains of the temple of Mithras fifty of so years after Wheeler's visit. It's situated in a field not far from Hadrian's Wall and it gives the visitor a sense of what it must have been like for the Romans who found themselves in this alien land. It's a strange, dark and freezing place but at least they have the certainty of good old Mithras to provide heat and light.

I remember being given homework once during a Chemistry lesson at school. We had to describe how each of us could still be breathing in particles of Julius Caesar's dying breath. I submitted the usual rubbish, complete with several thus's and therefores and probably one or two ergo's, in a futile attempt to conceal that I hadn't a clue what I was writing about. My teacher was more astute than I thought and he gave me a 'Must try harder'. Despite his valiant efforts in explaining it to me, I still couldn't grasp the concept (and my grasp is no less tenuous now than it was then).

Visiting the cold stone of the remnants of a temple in Northumberland made much more sense to me. It was a sort of no man's land where the past and present mingle and breathe the same air. I get the same feeling from The Grandeur That Was Rome, except this time there's the double whammy of watching an old bloke from way back discussing characters and events that were ancient history even to him.

Sir Mortimer Wheeler died in 1976 at the age of 85 but he was still appearing on screen as late as 1974 in the programme Sir Mortimer and Magnus. The clips I've seen have been rendered almost sepia by the washed-out colour, and the grainy outdoor footage clashes with the sharper pictures captured indoors. Graded grains make finer film. Yes, we're in the 1970s right enough.

The Magnus in question is Magnus Magnusson. It is a series of six interviews lasting 15 minutes or so in which Wheeler recounts tales of past archaeological digs. In the style of John Freeman's Face to Face, the excellent Mr Magnusson is sufficiently self-effacing to have the camera point directly at the subject with minimum cutaways to the interviewer's nodding head. Mortimer Wheeler is clearly enjoying himself and why shouldn't he? He's in his eighties and the host of Mastermind has brought a film crew with him to hang on his every word. He must have felt like a giddy sixty year old again.

One of the current buzzwords is legacy. We are all concerned about what history will think of us when we're gone, even though we won't be around to find out. Emperor Hadrian and the rest have nothing to worry about and I think Sir Mortimer Wheeler can be equally proud of the televisual fragments he left behind.

Thanks to the BBC iPlayer, evidence of his work can be viewed by anyone in the UK. The iPlayer is a great resource and it's one of the reasons why I love television. You can find loads of interesting stuff without having to leave your front room. It's just a question of knowing where to dig.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on August 22nd, 2021. Written by Andrew Coby for Television Heaven.