The Young Pope

2016 - United StatesReview: John Winterson Richards

While it may seem odd to describe a 2,000 year old organisation as glamorous, only the British Monarchy and the American Presidency can compete with the Papacy when it comes to sheer style in the display of power, all the more impressive when it is "soft power."

What gives the Papacy the edge over the others is its carefully cultivated air of mystery. The Pope has far more control over his organisation than any Constitutional Monarch or elected Head of State, but is selected by a secret Conclave nominated by his predecessors. The line of succession to a Monarchy is well known in advance, and a Presidential election will usually come down to the nominees of the major parties, but no one can know who the next Pope will be. Although there are always favourites, and they often prevail, there have been enough outsiders elected to give substance to a Vatican proverb: "He who goes into the Conclave a Pope comes out a Cardinal and he who goes in a Cardinal comes out a Pope."

This potential for a dramatic reversal has generated to a whole branch - or at least a twig - of fiction in which someone completely unexpected is elected to the Chair of Saint Peter. It got off the ground with Frederic Rolfe's wish fulfilment novel 'Hadrian VII,' and went on to include the likes of Walter F Murphy's 'The Vicar of Christ' and Morris West's 'The Shoes of the Fisherman,' which became a major feature film with Anthony Quinn.

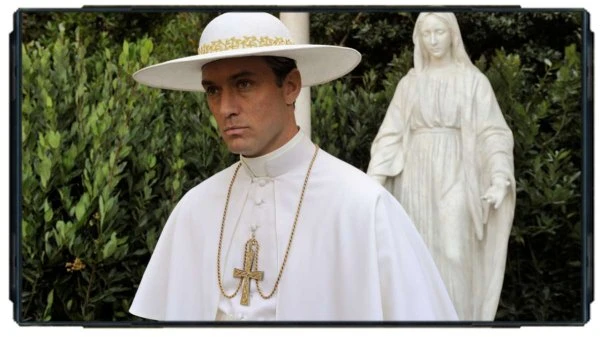

So The Young Pope is part of a well established tradition. It begins with the compromise election of Lenny Belardo (Jude Law), the youngest Cardinal - a mere child in his forties. The senior Cardinals assume they will be able to guide this youngster in the direction they want to go. However, it turns out that Lenny has a will of his own. He takes the name Pius XIII, which is considered ominous, Pius being the name of several Popes now deemed reactionary.

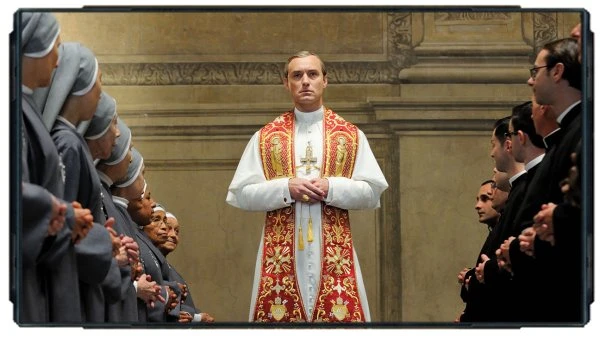

Indeed, Lenny appears to have a definite strategy, to increase - or, as he sees it, restore - the sense of mystery surrounding the Papacy. To this end, he never shows his face in public and demands total submission to his authority. This "obscurantism," a rejection of reason in favour of an irrational acceptance of the obscure because it is obscure, shocks the Cardinals, who, like all recent Popes, have spent their whole careers trying to move the Church away from that image. It is a nice twist on the literary tradition in which it is usually the outsider Pope who is the force for greater openness and the Vatican hierarchy which resists it.

Nevertheless, Lenny is the Pope and the Cardinals must obey. He seems to have complete confidence in his strategy, while simultaneously undermining the confidence and strategy of his opponents with unpredictable disruptive decisions that leave them off balance and uncertain how to react - possibly a reference to Donald Trump's political methods. They have no idea that behind this façade of certainty is a man deeply unsure not only of his plans but also of himself and his faith. It becomes apparent that Lenny is in fact a charlatan.

As his strategy is revealed as little more than bluster, it fails. Yet there is redemption: Lenny is able to retrieve his public standing as he comes to realise that there is sufficient mystery in faith, and in the world, without him having to add his own artificial version.

Law, an actor who divides opinion, is well cast here and does some of his best work. He preserves a nice ambiguity, so that we never quite make up our minds about Lenny, but we do find ourselves developing a growing sympathy for him.

He is backed by a strong international cast. It is dominated by Silvio Orlando as Cardinal Voiello, the Vatican's Secretary of State, Cardinal Chamberlain, and chief fixer. Outwardly a vain, egotistical, calculating bureaucrat whose self-deprecating manner hides an arrogant and ambitious politician, he turns out to be a very human being of many layers, and the more they are revealed, the more we like him - we never quite get that far with Lenny himself.

James Cromwell is his usual powerful presence in a poorly written role as Lenny's disappointed mentor and surrogate father. Diane Keaton, who can never be anything less than good, is Sister Mary, the nun who raised Lenny and it is a pity the character is never really developed. Allison Case plays her very attractive younger self - a substitute mother guaranteed to leave any adolescent boy in her care somewhat confused.

Javier Camara is good as a Saintly looking Cardinal with a couple of fairly predictable secrets. Cecile de France brings some much needed sex appeal to the Holy See as its very modern marketing adviser. Ludivine Sagnier shows a poignant vulnerability as a woman desperate for a child who seems to be the only person to believe in Lenny.

However, the real reason to watch The Young Pope is Paolo Sorrentino, the director. Darling of art house cinema, Fellini's Number One Fan, and arguably one of the best visual directors of his generation, possibly of all time, it is extraordinary that someone of his stature took on the task of directing an entire television series, as well as co-writing it.

The result is positively gorgeous. He brings his cinematic sensibility to the small screen without any loss of the sense of epic. All serious cinephiles should watch The Young Pope: if they do not get into the story they can always amuse themselves by playing "spot the Fellini reference" - or looking for references to Sorrentino's own films, which is often much the same thing. There are plenty of both. If some of his more surreal images and sequences seem out of place in the narrative (what was that business with the kangaroo?), and frankly pretentious, they are still perfectly photographed.

His use of light and shade is masterly as ever. So is his use of alternative locations and the sets at the legendary Cinecitta studios - including what must be the same replica of the Sistine Chapel used in The Two Popes - to cover for the fact that he obviously could not film in the Vatican itself. It is clear that a lot of money has been spent on the production.

It is therefore doubly regrettable that Sorrentino the director was not given better material by Sorrentino the co-writer and his fellow scribes. This is not to say is a bad script. On the contrary, it is full of interesting ideas and thoughts. It is simply not worthy of everything else that has been put into the production.

It never really decides if it is a satire or a drama, and so ultimately fails as both. It was not really sharp enough for the former and seemed to aspire to the latter, in which case the surreal and absurd touches kept getting in the way. Too much was unrealistic for there to be serious consideration of what might, just might, have been real.

For example, how likely is it that a man could rise to the rank of Cardinal in a system famous for its strict scrutiny without his views and character being the subject of considerable investigation? Moreover, how could he serve as Archbishop of a major city without numerous photographs being taken of him? It would be unlikely at any time, but in the internet age it is inconceivable.

Most unconvincing of all is the portrait of a positively irreligious Church. It is not only Lenny but the whole hierarchy that seems plagued with doubts. There is not one realistic portrait of a person of faith. All the characters talk like people in a play, a play written by someone without religious belief who is projecting his own assumptions on to them. Committed Christians usually do not talk and think as they do in The Young Pope. God is disparaged, Jesus is barely mentioned, and people who know from their reading of the Gospels that there is only one unforgivable sin, blasphemy against the Spirit, are very casual about how close they come to it.

This begs the question whether only people of faith can understand the mindset of people of faith sufficiently to be able to write about them with authenticity. If so, The Young Pope is not the only project to fall victim to a much bigger problem. Although it was not always so, the mainstream of literature, the arts, and the media is not a place where faith and people who take faith seriously are usually welcome at the moment. Their voices - the voices of the majority of the population who have some sort of faith - are underrepresented in deciding what goes on television. The voices of the positively anti-religious, or at least those who are uncertain or wary of religion, are stronger. It is their external perception of faith, rather than the internal experience of the believer, that is more likely to find its way on to the screen.

So, although The Young Pope has all those interesting ideas and thoughts, ultimately it lacks substance. It also lacks a conclusion - in spite of its rather melodramatic ending. Or does it? A sequel, The New Pope, made by the same production team with most of the same main cast and characters, is in many ways a continuation. However, The New Pope is sufficiently distinct - above all in its casting of that habitual game changer John Malkovich - to merit its own discussion, perhaps at a more appropriate time.

As for The Young Pope itself, it asked a lot of questions to which it offered no answers. While some might say that is the nature of faith, in purely dramatic terms a truly glorious production deserved a bit more clarity about what it was trying to do.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on June 4th, 2020. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.