Three Gifts for Cinderella

1973 - Czechoslovakia E Germany‘It is the snowscapes in the actual land of Good King Wenceslas that made Three Gifts for Cinderella a Christmas film and gives it such a distinctive visual style that sticks in the mind’

Review by John Winterson Richards

A very popular European feature film known in Czech as Tri orisky pro Popelku (Three Nuts for Cinderella) and in German as Drei Haselnusse fur Aschenbrodel (Hazelnuts for Cinderella), having been coproduced by Czechoslovakia and East Germany, was bought by the BBC as part of their strategy of filling children's television with cheap imports, divided into three episodes, and shown quite frequently in the 1970s as Three Gifts for Cinderella (it was titled Three Wishes for Cinderella in other English-speaking countries). In this form, it became a much-loved favourite for British children of that generation.

Most of those children were wholly unaware of its cinematic origins and, as adults, are probably unaware of how the film version remains to this day something of a "cult" item in its native lands and in much of Central, Northern, and Eastern Europe. Showing it at Christmas every year has become something of a tradition on Czech, Slovak, German, Swiss, and, for some reason, Norwegian television. Whatever the reason, the Norwegians love it so much that they recently made their own version with the ubiquitous Kristofer Hivju.

Moritzburg Castle in Saxony, which provided the exterior for the Royal Palace scenes, has a bronze replica of the Cinderella character's slipper at the very spot on the steps where she left it in the film, and is currently, at least at the time of writing (December 2023), running a special exhibition to mark the 50th Anniversary of its first showing - until 25th February, 2024, if you happen to read this in time. Also, at the time of writing there is a page dedicated to other locations in the film on the Visit Czechia website. A recent digital restoration of the original film involved experts from several nations and was funded in part by the European Economic Area.

What has come to be called "the Cinderella story" is, in its general form, possibly the most basic and archetypal of the basic story archetypes: in essence, a virtuous but poor and powerless protagonist is suddenly propelled by unexpected events to acquire wealth and power. This wealth and power is often accompanied by love. There is often a difference in traditional tales in that the male protagonist often earns the right to a high status bride as a result of his new wealth and power while the female protagonist usually gains her wealth and power as a result of acquiring a high status husband. The story in both cases is therefore intended to encourage the virtues considered necessary to attract a high status mate. It is not difficult to see the appeal of such stories: most people feel relatively poor and powerless; they like to think they are virtuous and deserving; they like the thought of power and wealth, and possibly, if they have not found it already, love; and even more they like the thought of these gifts coming quickly and without much effort, or, better still, in reward for previous unrecognised effort.

Variants of the story are found across cultures. There are examples in the Bible, Greek mythology, the Arabian Nights, and Arthurian Romance. It was the early First Century geographer Strabo who introduced the element of a Royal with a strange obsession with the notion that shoe size is a reliable indicator of matrimonial compatibility.

The classic version of Cinderella, the one most people know because it was adapted by Walt Disney into one of his greatest animations, is found in the Contes, the folk tales collected at the end of the 17th Century by Charles Perrault, a retired French civil servant who wanted to amuse his own children and at the same time augment his meagre pension.

A slightly different version is found in the German folk tales collected by the academic Brothers Grimm in 1812. This includes several elements not found in Perrault that are referenced in Three Gifts for Cinderella, including a request for a costless gift that turns out to be very valuable, a hazelnut tree, and some very helpful birds rather than a Fairy Godmother. Just as the name Cinderella, the feminine diminutive of cinders, is derived from her habit of sleeping in the cinders of the fire to keep warm, her German equivalent is called Aschenputtel, which translates literally as "Little Ashes Girl" or "Dirty Ashes Girl." In the Grimms, Aschenputtel plants the gift of a hazelnut on her mother's grave where it grows into a significant tree.

It is a Bohemian variant on the German story from the pen of the Czech nationalist writer Bozena Nemcova in the early 19th Century that provides the direct source material for Three Gifts for Cinderella. How much is traditional Bohemian folklore, how much Nemcova, and how much the adaptor Frantisek Pavlicek, only a Czech scholar can say.

What we can say is that for British children it had the double appeal of a slightly exotic spin on a familiar story. This is the secret of the success of a great many foreign imports: viewers like something a bit different but not too different, and this was definitely the case with Three Gifts for Cinderella.

Yet even at the age of about ten, your future reviewer was politically conscious enough to be surprised that two Communist Republics had produced a version of a story in which Royalty and nobility were presented as objects of aspiration. This assumption is understandable in Perrault, who had been Secretary to Louis XIV's Minister of Finance Colbert, but one would have thought it ideologically unacceptable in East Germany, one of the most militantly Socialist members of the Warsaw Pact, and while the regime in Czechoslovakia had been relatively "liberal" by Communist standards, the Soviets had stamped down hard on that relative "liberalism" only a few years before in 1968.

The charming fairytale Three Gifts for Cinderella is therefore a strange product of brutal materialist totalitarianism. The scriptwriter Pavlicek was himself "blacklisted" by the Socialist authorities at the time and wrote under the name of another writer, Buhumila Zelenkova. Only the film's director Vaclav Vorlicek and a studio executive were aware of "Zelenkova's" real identity on this occasion.

However, reviewing the film as an adult, one becomes more aware of its subversive streak. The Royals and the Nobles are all presented unsympathetically. Even the Prince who is supposed to be the object of our protagonist's desire is an idiot. Although the legitimate heir to her family estate in accordance with storytelling tradition, Cinderella - let us stick to the most familiar version of her name - seems to identify with the servants: she is treated as one, she is kind to them, and she is popular with them. Her kindness brings its own reward, and the workers join with her in rejoicing in the humiliation of her stepmother and stepsister, symbols of the corrupt and selfish Aristocracy. There is a definite class warfare subtext to the script, which probably helped get it past the censors.

It is nevertheless an unashamedly romantic story and understanding this was the key to its success. Its wonderful evocation of the air of romance is due in very large part to Vorlicek's decision to postpone what was originally intended as a Summer shoot for several months until Winter. It is the snowscapes in the actual land of Good King Wenceslas, who was Duke of Bohemia in what is now Czechia, that made Three Gifts for Cinderella a Christmas film and gives it such a distinctive visual style that sticks in the mind. The romantic feeling is enhanced by stunning location work in Czechoslovakia and East Germany, and by a splendid soundtrack.

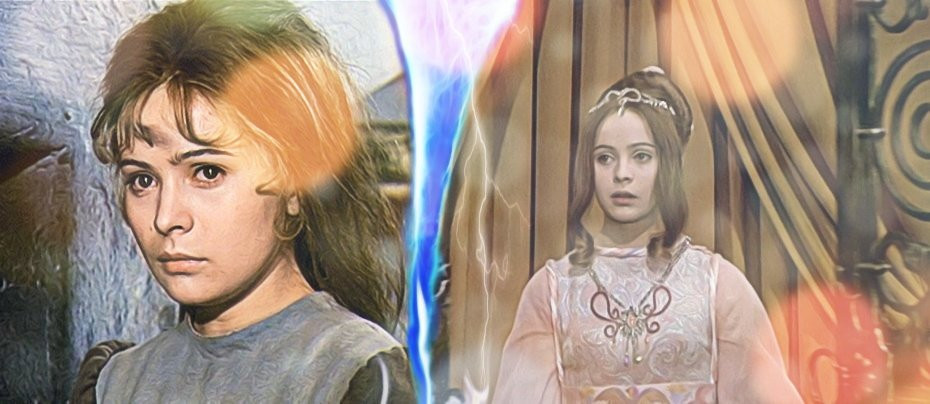

Also crucial to the film's success is the casting of Libuse Safrankova in the leading role, despite her not being Vorlicek's first choice. Although nineteen at the time of filming, she has the wide-eyed innocence and vulnerability of a younger girl, which makes her more sympathetic than most teenagers. That said, rewatching at an age when she could be one's granddaughter, one feels uncomfortable at the thought of such a young looking girl being considered of marriageable age, in spite of the fact that nineteen was considered almost past it in the Middle Ages when this version of the story was set.

One also feels uncomfortable at the hunting scenes, especially when Cinderella's love for animals, including her horse, her dog, her cat, the very obliging doves and pigeons, and an owl with undefined powers, is an important part of her character and the plot. A love of animals is by no means incompatible with hunting, but it seems quite shocking when Cinderella shoots down a bird of prey - happily, not her pet owl who, apparently, provided her with her hunting outfit. One cannot imagine anything similar in a children's show being commissioned these days.

Finally, one remains very uncomfortable indeed at the thought of her marrying the idiotic Prince. He is childish when we meet him and he shows no growth at all throughout the story. One is left with the feeling that she is far too good for him and that, in reality, they would be unlikely to live happily ever after.

One often feels this about Princes in fairytales, that they are no more than trophies, objects of desire for female protagonists, just as fairytale Princesses are for male protagonists. While the "Cinderella" story archetype will never be entirely out of fashion, one can understand the reason why it is disliked by feminists and by those who feel, more generally, that it is a better moral lesson if a protagonist of either gender is seen to "earn" their "reward" through their own efforts rather than prevail through a convenient turn of events - even if real life is a combination of both efforts and events. To a great extent, Three Gifts for Cinderella is well ahead of its time in meeting these objections. It gives its Cinderella her own agency. She is often held back by her own lack of self-confidence and she must make the positive choice to overcome it. She is given options by her magical owl - to be honest, it is never made clear how this all works - but she must decide whether or not to make use of what she is offered. In the end, she is not driven to the Ball in a transformed pumpkin. She rides there herself on the horse for which she has been caring. So the final paradox of this traditional tale of Aristocrats adapted by Communist regimes is that it emphasises the importance of being prepared to act when opportunity arises - a moral perhaps more suitable for an entrepreneurial culture than either Aristocracy or Marxism.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on December 22nd, 2023. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.