Desert Crusader (Thibaud ou les Croisades)

1968 - FranceReview by John Winterson Richards

Children's television has rarely attracted big budgets. There was certainly true of the BBC in the 1960s and 1970s. There seems to have been an assumption left over from its monopoly days to the effect that if you sat the brats down in front of the box with anything loud on it they would probably stay there.

Following this assumption, they bought a lot of foreign programmes cheaply and dubbed them to pad out the schedules.

Yet the unintended consequence of all this was that a generation of children was exposed to some television that was in many ways far more interesting than some of the supposedly more sophisticated children's programming today. For a start, being foreign, it gave them a glimpse of other cultures while at the same time making the important point that, beneath those superficial cultural differences, people are basically the same the world over.

Since many of the acquisitions were not originally made specifically as children's shows, they introduced the children to some more grown up themes, and paid them the compliment, which children always appreciate, of being treated like adults. It is the classic mistake of children's television to assume that children want to identify as children and with other children.

Above all, some of the purchases were programmes of high quality, or at least of higher quality than children's television budgets could have produced domestically.

Among the most memorable for those of us who grew up in the 1970s were French family friendly adventure dramas such as The Flashing Blade, Desert Crusader, and The Aeronauts. Although they were not made as children's shows, they became fixtures in children's programming in the UK, and tend to be recalled fondly by British adults of a certain generation.

What made Desert Crusader memorable was an energetic titles sequence, full of sword fighting and lots of people galloping about on horses, all driven by a thundering theme from the distinguished composer Georges Delerue, who also wrote the score for 'A Man for All Seasons.'

Dramatically, that sequence was probably the best part of most episodes. Their plots were straightforward and predictable, as was to be expected given a running time of less than half an hour. If anything, they should be commended for fitting a lot into a short space, even if they did not have the opportunity to explore anything in depth.

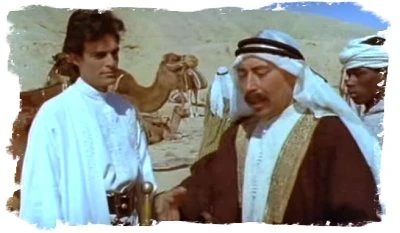

This is a pity because some of the characters, story ideas, and themes were potentially very interesting, and these days would probably merit 45-60 minute episodes. Indeed, the basic premise seems more topical than ever: a handsome young knight, the son of a French baron and a Christian Arab, seeks to keep the peace between Christian and Muslim in the 12th Century Holy Land.

It is a curious historical fact that the inhabitants of the "front line states" in the Crusades were indeed, if not exactly tolerant, at least fairly pragmatic. There were Christians living peacefully in some Muslim states and Muslims living in Christian realms of Spain, Sicily, and the Crusader "Kingdom of Jerusalem," where Desert Crusader is set. Troublemakers on both sides, both Christian and Muslim, tended to be travellers or immigrants from further away, who had nothing to lose and everything to gain by starting fights.

So our hero, Thibaud, the eponymous 'Desert Crusader,' is in the strict sense not really a Crusader at all. On the contrary, his mission is to prevent further Crusades, and "wannabe" Crusaders are part of his problem. Back in France, the programme was known as Thibaud ou les Croisades - which could be translated literally as 'Thibaud or the Crusades,' giving a more accurate sense of what it is really about.

These issues of racial and religious conflict and accommodation are pretty heavy for a supposed "children's programme.' Yet the message was clear even to a ten-year old: we wanted to be like Thibaud because he was so obviously heroic and Thibaud wanted to get along with everyone, therefore we should want to get along with everyone.

It is only in retrospect that one realises that there was yet another dimension to this meaning of the show, one of which most children, or at least most British children, were totally unaware at the time. In 1962, only six years before it was made, the French had been effectively run out of Algeria, a country which many of them considered an integral part of France. About 800,000 French people living there who considered it their home had fled to actual France.

This was a great blow to a proud nation, already battered by the Second World War and by being run out of Vietnam in an even more humiliating fashion. So these French adventure shows can be seen as part of an attempt to restore their self image: in The Flashing Blade, France takes refuge in memories of her glorious past history, while The Aeronauts paints a more futuristic picture of France as a modern, dynamic, technologically advanced world power.

Although Desert Crusader is obviously part of the same process, it offers something else as well: the half-French, half-Arab peacemaker Thibaud was a symbol of reconciliation in and after Algeria, and any adult French viewer would have recognised that in 1968, the turbulent year for French politics in which Thibaud ou les Croisades was first shown.

So what was presented to British viewers as a "children's programme" was still at the time a highly charged political drama in its country of origin. The BBC executives who bought it could not have been unaware of that.

Curiously, much of the truly splendid location work was done in Morocco and Tunisia, frequent stand-ins for the Holy Land, which just happen to be on either side of Algeria. More shooting was done in and around the spectacular fortified town of Aigues-Mortes, which had served as a major depot for the Crusades and which is located in the South of France, the region where the refugees from Algeria, 'les Pieds-Noirs,' settled in large numbers and formed a significant proportion of the population.

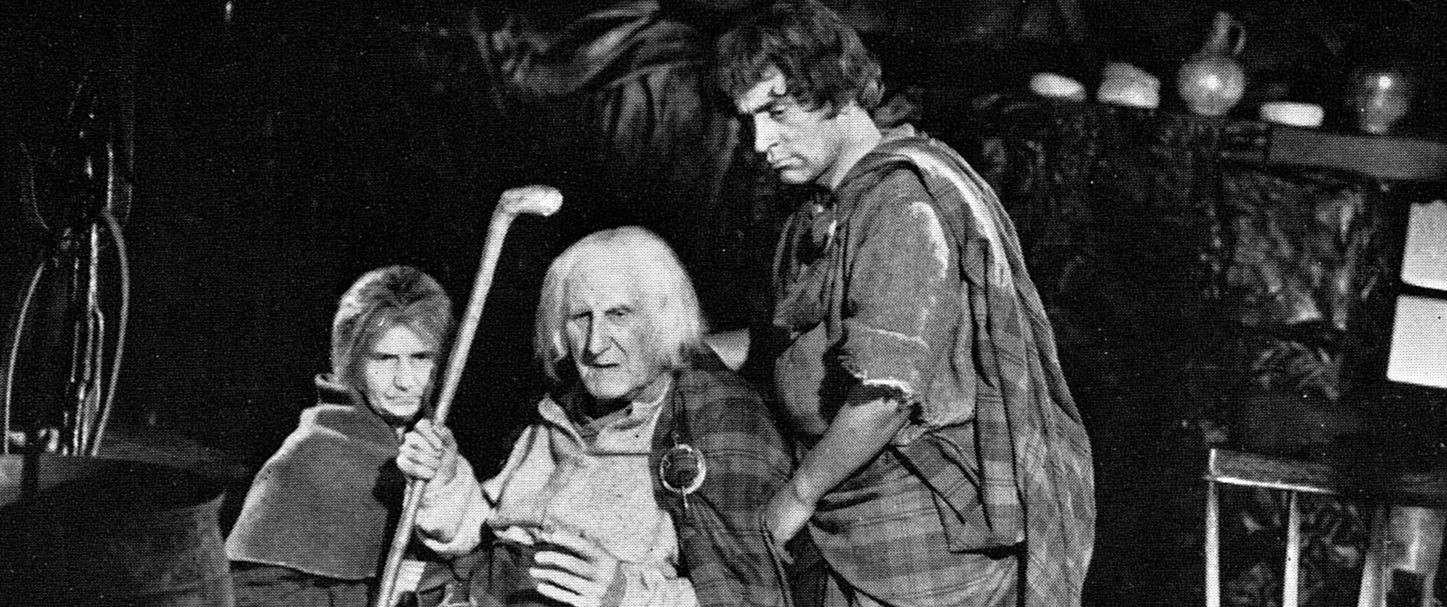

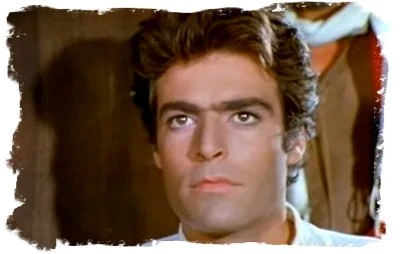

Thibaud was played by handsome Canadian Andre Lawrence, another in the seemingly endless tradition of unfairly good looking men on French television. Even his greatest fans would probably admit that his looks were not matched by his acting abilities, and it is reported - on Wikipedia, so make of it what you will - that he was dubbed by another actor in the original French version for the whole first season. He certainly seems to have had trouble finding work as an actor later and eventually quit acting "pour se consacrer a la spiritualitie" - Wikipedia again, but it would be nice to think that it was true this time, because it would be so in keeping with his character of Thibaud to dedicate himself to Spirituality.

For, whatever else, Thibaud was the very picture of the perfect hero. He even rode about the desert in an absolutely spotless white robe - not something anyone could do for long in reality: even if the 12th Century had the technology to produce anything that bright, it would not have remained so for five minutes in the sun and the dust of the Middle East.

Apart from this absurdity, the production values of the show were generally good, despite what appear to have been fairly tight and diminishing budgets - there is a definite decline between its first season and its second. A lot of effort seems to have gone into costumes, sets, and props, which, combined with the extensive location work under cloudless blue skies, give the whole production a wonderful glow of light and colour.

In spite of the relatively small number of extras, not all of them comfortable with horses or swords, the big set piece scenes - such the Knights Templar riding in force out of their Castle to more Delerue power chords and later defending against a camel charge at an oasis - are handled with skill and tend to stick in the memory.

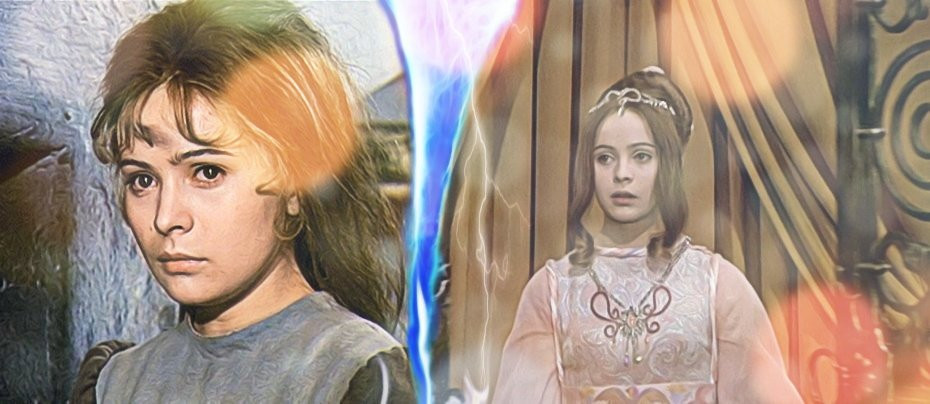

There are obvious parallels between Desert Crusader and Sir Ridley Scott's historically erratic epic Kingdom of Heaven almost forty years later. Both have heroes who are simultaneously local nobleman and outsiders trying to maintain peace between people of different religions. Both even attract the eye of a Princess Sibylla - not the same one, because Desert Crusader is set in a more optimistic time about a generation before the events of Kingdom of Heaven, which were exactly what Thibaud was trying to prevent.

Indeed, Thibaud is ultimately the more credible and sincere of the two protagonists. Since producers seem to be obsessed with "reboots" these days, the thought occurs that he might be a role model and symbol of reconciliation with something to say to our own times.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on March 30th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.