Charlie Drake

With his diminutive stature, red curly hair and childlike mischievous manner, Charlie Drake was described by one critic as looking like 'a Botticelli cherub.' A physical comedian who mastered the art of slapstick, often articulated in an outraged falsetto when things went wrong, which they invariably did, he successfully moved from children's to adult performer and in the process became one of Britain's top television stars of the 1950s and 60s.

Charles Edward Springall was born on 19 June 1925 in the Elephant and Castle area of South East London. His poverty stricken family of mother, father and six children, of which he was the youngest, were so poor that his mother had to pawn the sheets and pillowcases they slept on every Monday only to retrieve them every Friday so they would be able to enjoy the comfort of them at the weekend.

All six children were sent to work as soon as they were able and Charlie contributed by doing a paper round in the morning and selling horse meat for cats in the evening.

In 1933 Drake got his first taste of showbiz when he was part of the chorus at the South London Palace as support for the music hall singer and comedian Harry Champion. The gig lasted for one week and Drake was paid half-a-crown. It was enough to light the spark that would lead him to pursue a career in entertainment. After leaving school he toured working men’s clubs refining his act with each appearance, but in 1939, with the outbreak of the Second World War, he joined the RAF and was sent to India where he started producing and performing in entertainment shows for the troops.

Upon discharge at the end of the hostilities Drake was confident enough to audition for the famous Windmill Club in the West End of London. In fact, he auditioned unsuccessfully no less than six times. Despite the constant rejections he managed to find semi-regular work appearing in variety shows during the summer and festive seasons and when not employed ‘treading the boards’ he worked in a ball-bearing factory and was also a cakemaker.

During one of his failed auditions, Drake met up with Jack Edwardes who he had previously served with in the RAF. Edwardes, a 6ft 4in comic who had been specialising in pantomime dames, was also rejected by the Windmill, and suggested that the two of them team up as a double act. A short while later, Edwardes was appointed entertainment producer at a holiday camp and promptly booked himself and Drake as the double-act Mick and Montmorency, a clumsy duo set in the Laurel and Hardy mode, with Drake taking most of the pratfalls. During this run producer Michael Westmore spotted them and decided that their brand of comedy was ideal for the BBC children's programme Jigsaw.

In 1955 the newly founded Associated Rediffusion company signed them up as the first children's comedy double-act for ITV and they debuted on Independent Television on 30 September for 22 15 minute fun-filled disastrous adventures where they appeared in a variety of jobs from removal men to scientists.

At the end of the second run Drake decided he had had enough of children's TV and wanted to aim his material at adults and he and Edwardes went their separate ways. Drake was approached by the BBC’s Head of Light Entertainment, Ronnie Waldman, to come up with a single half-hour comedy. Laughter in Store was broadcast in January 1957 and Drake co-starred with Charles Hawtrey and Irene Handl. The BBC were suitably impressed and immediately ordered a full series to be called Drake’s Progress. Irene Handl joined up with Drake once again and Warren Mitchell and Willoughby Goddard joined as regulars. Among the writers for the series were future Morecambe and Wise scriptwriters were Sid Green and Dick Hills. It was around this time that Drake established his catchphrase “Hello, my darlings!”

Over the next few years Drake made several shows for the BBC but this ended abruptly when an accident left him seriously injured during a live broadcast. Drake had arranged for a bookcase to be set up in such a way that it would fall apart when he was pulled through it during a slapstick sketch. It was later discovered that an over-enthusiastic workman, thinking the prop was broken, repaired the bookcase before the broadcast. The actors working with him, unaware of what had happened, proceeded with the rest of the sketch which required that they pick him up and throw him through an open window. Drake fractured his skull and was unconscious for three days. It would be two years before he returned to the screen.

In 1963 he made his return to television with ITV in The Charlie Drake Show , a compilation of which won the Charlie Chaplin Award at the Montreux Festival in 1968. But it was his 1965 series, The Worker, which elevated Drake to the status of national treasure. When we were first introduced to The Worker he had already been found, and dismissed from 980 jobs over a period of 20 years, much to the frustration of local Labour Exchange counter clerk Mr. Whittaker (Percy Herbert), whose job it was to relocate him from the counter of his Weybridge office, where Drake would bang on the counter every other morning, into permanent employment.

It is perhaps the second series of The Worker that is best remembered, when Percy Herbert was replaced by Henry McGee as the new clerk, Mr Pugh, a name which Drake could never pronounce, instead referring to him as "Mr Peooh", the merest mention of which would lead the Labour Exchange official to lift 5ft 1in Drake off the ground by the scruff of his neck. These two were the only regulars on the series with a constantly changing supporting cast as Drake tried out a different job in every episode, without success.

Drake’s next series for ITV was Who is Sylvia but it didn’t meet with the same success and in 1971 he returned to The Workerfor another two series.

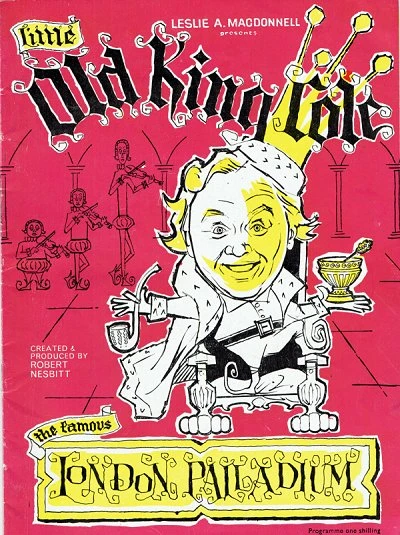

By 1972 Drake was less in demand on television but was still a draw on the theatre circuit although he had something of a growing reputation for being difficult. When he appeared in panto at the London Palladium, Drake not only insisted on the star dressing room but demanded that it be redecorated and furnished to his own taste. Then in 1974 he fell foul of the unions when he attempted to bring a local woman, not a member of Equity, into his show at the Bradford Alhambra.

Drake refused to release the woman and the union complained to the Provincial Managers' Association. Following a hearing he was fined £760 for putting the show in jeopardy. He refused to pay, and Equity suspended him from any provincial theatre for a year. This coincided with his drop in popularity with television audiences and Drake began to struggle financially later admitting to having gambled away most of the fortune he had made in his heyday. During that period, Drake had not only had a string of popular shows but also made a number of comedy records such as ‘My Boomerang Won’t Come Back’ and ‘Mr Custer’ and appeared in several (although not very successful) British comedy movies. At one point he owned 14 racehorses, a mansion in Surrey, two of the world's most expensive cars, a yacht and “spent the rest on gambling.”

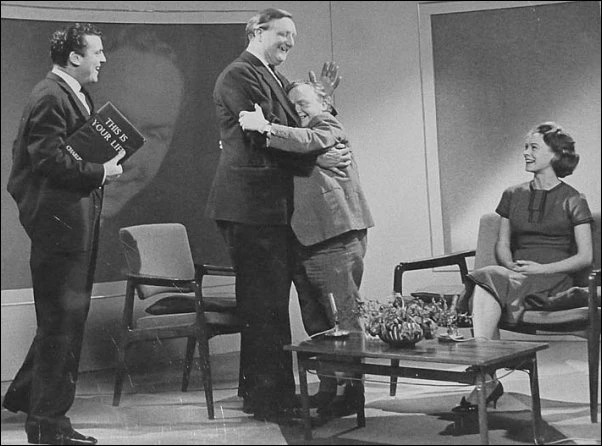

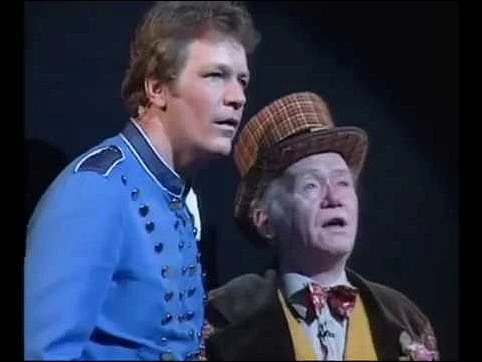

It wasn’t until 1978 that Drake reappeared regularly on television. As part of Bruce Forsyth’s Big Night Out he returned in his most familiar role. That of The Worker. The series only ran for eight shows and the format was only ten-minute sketches. Although he was to make the occasional comic guest appearance on television after 1978, Drake moved largely onto straight drama, with Shakespeare ( As You Like It) and Pinter on stage, giving an award-winning performance as Davies in Pinter's The Caretaker in 1983, and a well-received performance on television as the unscrupulous moneylender Smallweed in Bleak House.

Into the 1990s he continued to appear in smaller roles in stage productions including notoriously smutty pantomime Sinderella with Jim Davidson. Drake’s appearances are the highlight of the show, even though he was constantly forgetting his lines and having to ad-lib. This was nothing to do with his advancing years as Jim Davidson would testify: "Blimey, the whisky off his breath would knock you out!"

In 1995 Drake suffered a stroke which brought down the curtain on his career. He moved into Brinsworth House, a retirement home for actors and performers, run by the Entertainment Artistes' Benevolent Fund, and stayed there until his death on Christmas Eve 2006.

Charlie Drake delighted audiences with his slapstick comic antics in stage variety shows and on television for more than 50 years, often playing a downtrodden "everyman," who failed at everything he tried. Not so in real life. He wrote many of his own scripts and would rehearse over and over again until he got what he wanted. As a result, he was often called 'difficult.' Laurie Mansfield, his manager for 37 years admitted "He was probably the most stubborn man I ever met. He knew what he wanted and would not accept compromise on getting what he wanted." He said without his brand of slapstick humour, in which he did his own stunts, there would have been "no Michael Crawford, no Frank Spencer". "His timing was acknowledged by everybody as being the very very best. He was a great great comic talent."

Published on May 20th, 2020. Written by Marc Saul for Television Heaven.