A Subject of Scandal and Concern

1960 - United KingdomJohn Osborne's first play for television was turned down by one commercial television company and bought - but not produced - by another before it was snapped up by the BBC. According to Osborne, Granada Television had been badgering his agent for some time to write a play for them, but he had repeatedly declined.“ Then suddenly I had nothing better to do and I thought that simply as an exercise I would write one” Osborne told the London Daily News in March 1960.

Granada rejected it.

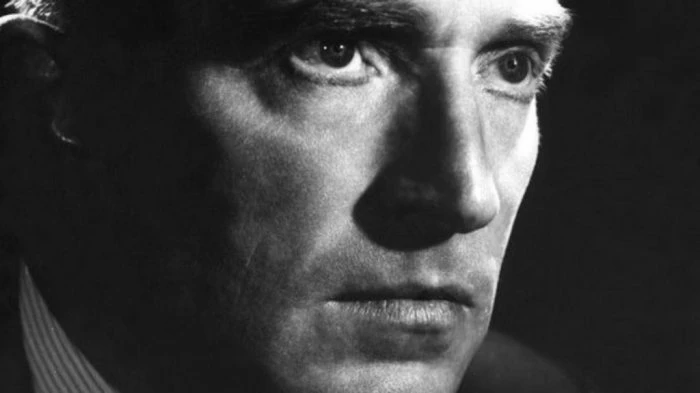

The head of Granada's drama department was quoted as saying "It was Mr. Osborne's first television play. Let's leave it at that." Lloyd Williams, then assistant controller of programmes for Associated-Rediffusion to whom the script had been sent, offered only faint praise. "We think he (Osborne) has a slight talent for TV. We would like to give him a bit of encouragement." According to Tony Richardson, an old colleague of Osborne's, "A-R agreed to do it and the whole thing was set up. Richard Burton had agreed to star but could only fit it in if it was done at once. Then it turned out that A-R couldn't handle it. Their casting department said they couldn't possibly cast it in a few days. John was very angry and withdrew it and they agreed to release him from the contract." It was then that the BBC stepped in.

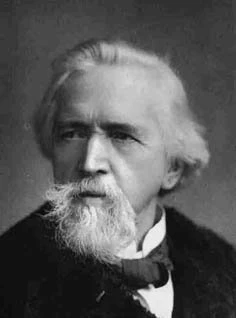

Scene One opens in the corridor of a jail and the camera fades on John Freeman, better known as the interviewer (some called him inquisitor) who, known for his often probing style, famously made Tony Hancock look visibly uncomfortable and Gilbert Harding cry on Face to Face, a BBC interview television programme originally broadcast between 1959 and 1962. Freeman is giving the background to the 1842 trial for blasphemy of George Jacob Holyoake, a poor young teacher and energetic member of the Social Missionary Society, who, in a lecture to Society members, denies the existence of God.

As a result, Holyoake was tried and became the last person convicted for blasphemy in a public lecture. It took an intervention by supporters to stop him being walked in chains from Cheltenham to Gloucester Gaol, and there was a formal complaint to the Home Secretary, which was upheld. Holyoake nonetheless underwent six months' imprisonment.

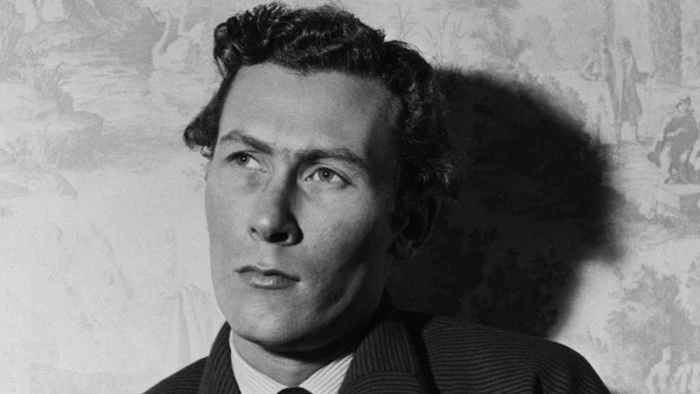

Freeman was uncomfortable in the role and managed to fluff his opening lines. He blamed this on producer Tony Richardson who changed the script - Osborne having written: "I'm a lawyer. My name's unimportant, as I'm not directly involved." But Richardson wanted Freeman to appear as the familiar face viewers were accustomed to on Face to Face. Freeman also felt uncomfortable about his surroundings as he explained in an interview in October 1960, a few weeks before the broadcast. "The studio set-up was vastly different from that of my usual programmes. Many sets, actors looking on, quite upsetting conditions. I could recapture nothing of the remote impersonal atmosphere I'm accustomed to."

Freeman's voice was heard through scenes at the Mechanics' Institute, the Assize Court, and the prison common room, and while reading a report from the local newspaper and reporting the trial aftermath. The drama was set out in its starkest terms with Osborne's intention being a plea for tolerance. The BBC managed to secure Richard Burton who came specially from Switzerland to tape the BBC production.

Even with an enigmatic star like Burton in the lead role and a support cast that included Rachel Roberts (as Mrs Holyoake), and Andrew Keir (Chaplain), the production drew unfavourable reviews from almost every critic, their main complaint being the staging rather than the acting. The Stage was particularly scathing as it reported: 'A-R and Granada were right about Osborne's dull play A Subject of Scandal and Concern Screened: 6 November (1960) BBC Television. If John Osborne has proved anything it is that Associated-Rediffusion and Granada TV were absolutely right in rejecting his first TV play.

It wasn't a play at all, but a series of dull tableaux interpolated with narration from John Freeman who, somehow, thought the whole occasion was important. Neither has Mr. Osborne written a TV play. It is plainly obvious that he doesn't know how to and I urge him to confine his future efforts to the theatre where he is definitely at his best.

To begin with the very opening puts viewers off. John Freeman tells us what we are about to see in a solemn, sober voice. In fact, the author feels he must explain himself at every opportunity imagining the viewers to be completely ignorant. From then on, each scene drags on and on as Mr. Holyoake (beautifully played by Richard Burton) explains why he doesn't believe in God. In return the believers explain why they believe.

The result is a mass of heavy dialogue, pretentious, uninspired, and as dull as can be. It may be that the story itself doesn't inspire one, yet it should do. Any man who fights for the freedom of speech and thought should be inspiring, but Mr. Osborne's treatment was so stagey, so slow, that little could be done to retrieve it. It was also plain that the director, Tony Richardson, didn't know quite how to treat it. His production laboured under the misapprehension that we were being given something really worthwhile.'

The Daily Herald's reviewer Phil Diack was even more forthright in his review under the headline 'What a mess this was Mr. Osborne!'

'I dare say that John Osborne was looking back in vexation last night when his first TV play "A Subject of Scandal and Concern" finally reached the BBC screen after it had been rejected by one ITV company and withdrawn by Osborne from another. The play had a late-night showing. Various explanations were given for this: That it was not suitable for children (because of the religious controversy in it I suppose): that the heads of the BBC thought so highly of its seriousness that they didn't want the usual clash with the ITV play. And more cruelly, that the BBC had lost their certainty of its merits since they recorded it in April. It was easy to understand why ITV turned up their noses at this particular pudding. It was mainly stodgy, and the few plums that it did contain were too rich and indigestible. Richard Burton, spectacles, impediment and all, sank his own creative talent into the character of the drab teacher who proved by his blasphemous denial of the existence of God that conscience can make heroes of us all. What an excellent programme some other writer of smaller talent could have made of it in say, Granada's "On Trial" series. It was a mess and a waste of all the talents. Most mistaken of all—if this was a play and not a documentary—was the use of John Freeman as narrator. This threw it entirely askew. Freeman's forte is actuality. Osborne's is theatricality in the strongest and truest sense. They certainly got their lines crossed.'

The Liverpool Echo offered the opinion that whatever Osborne writes 'will have a strong current of rebellion. But rebelliousness apart, it was hard to see in this occasionally rather flat-footed drama the brilliance of the author of 'Look Back in Anger.' The Birmingham Daily Post called the play an 'odd concoction of history and imagination' but was unsure how much of it was to be credited to the author and how much to Osborne's 'home work' in history. But it did decide that it was 'less of a play than a documentary programme showing the impotence of a lonely man against the bigotry of his times.'

The play was presented on stage in 1962 at the Nottingham Playhouse, perhaps with a view to eventually moving to a West End theatre, but again it failed to impress with The Stage again reporting: 'The transposition to the stage of the Playhouse, Nottingham, is done well but... straight, and tends to forget that something designed for one medium needs more in another than the absence of cameras. Directed by John Neville, who has to use distracting black-outs and scene changes every few minutes, it makes the lone struggle of George Jacob Holyoake more of an academic curiosity than a heart-searching light in which the audience can identify themselves. Daniel Massey's atheist emerges pure and towering over the bigots who besiege him, a powerful performance in which he seems like a dignified lion surrounded by yelping mongrels. It is a stimulating piece despite the shufflings on the stage as the sets by Rita Tayler generally one-dimensional are changed.'

A 2016 revival at the Finborough Theatre, London, was the first to draw a complimentary review. Michael Billington writing in The Guardian said: ‘Even if one wishes the play were longer and Osborne told us more about the historical context, Jimmy Walters’ production handles the multiple shifts of scene with great ingenuity. Jamie Muscato lends the stuttering Holyoake the air of a man driven to articulacy by palpable injustice and Caroline Moroney as his wife reminds us that others often pay the price for a hero’s principles. If nothing else, the play demonstrates that Osborne’s social rage was accompanied by a gnawing preoccupation with religion. ‘

After the transmission of the 1960 BBC Sunday Night Play production, it would be ten years before Osborne wrote for television again.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on April 22nd, 2022. Written by Malcolm Alexander for Television Heaven.