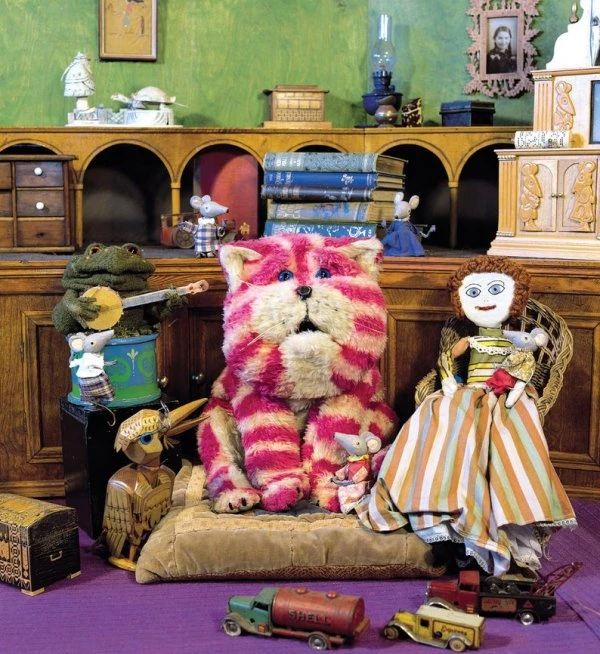

Bagpuss

1974 - United KingdomIn spite of appearing in only 13 episodes, Bagpuss was voted the most popular children's television programme of all time in a 1999 BBC poll. This was the correct result.

The stories were set in a "lost and found" shop owned by a girl called Emily, who would bring in various items she had discovered with the intention of repairing them and returning them to their rightful owners. She was assisted in this by the eponymous Bagpuss, a fat pink and white striped cloth cat who would come to life at the sound of Emily's voice:

"Bagpuss, dear Bagpuss,

Dear fat furry cat-puss,

Wake up and look at this thing

That I bring;

Wake up, be bright;

Be golden and light;

Bagpuss, O hear what I sing."

At which point Bagpuss would wake up, together with his friends, the Mice on the Marvellous Mechanical Mouse Organ, Madeleine the Rag Doll, Gabriel the Toad, and Professor Yaffle, a carved wooden bookend in the shape of a woodpecker. This waking would take the form of a transition from a montage of static sepia photographs with an omniscient voice over narration to a mainly stop motion animation in full colour with the dialogue being carried on by the various characters in their different voices. It was a brilliant representation of coming to life that set the tone for everything that followed.

Although there was some slight variation, the standard format of an episode was a debate over the nature of the object Emily had found, and some cleaning or restoration of the object, usually by the Mice, sometimes by a magical process prompted directly by Bagpuss' own thoughts. The debate took the form of songs, stories, or poems, illustrated by different types of animation or pictures, some of them quite exquisite. A few of the stories and songs were original but others had at least some basis in folk traditions or other sources.

The show was written, narrated, and co-produced by Oliver Postgate, who, with his producing partner, Peter Firmin, was responsible for a number of children's classics, including Noggin the Nog, Ivor the Engine, and The Clangers, through their legendary Smallfilms company.

For an organisation that produced so many masterworks, Smallfilms really does seem to have been almost a cottage affair in comparison with modern animation studios. In addition to providing the opening and closing narrations in his beautiful normal speaking voice, Postgate also gave individual voices to all the characters except Madeleine and Gabriel, who were voiced by the show's musical directors, folk singer Sandra Kerr and John Faulkner respectively. Former Art College lecturer Firmin provided the drawings and the models for the animation, assisted by his wife, Joan. Firmin's daughter, Emily, appears in period costume in the sepia photographs at the beginning and end of each episode as the Emily who owns Bagpuss & Co.

What seems incredible when one looks back at Bagpuss with the eyes of an experienced adult is how this small artistic team achieved total mastery of so many different techniques, including storytelling, poetry, song, sepia photography, different styles of drawing, and different forms of animation, even a bit of puppetry. It is like seeing the whole curriculum of an Art College crammed into less than three hours of screen time. A major Hollywood studio would employ hundreds of people to produce an animated feature of half its total running time with far less variety and imagination - and indeed has done so, quite frequently.

In keeping with the quirky, family atmosphere that seems to have surrounded the production, it is pleasant to read details like Madeleine was based on a clothes stand for the Firmin children, Gabriel on an actual toad who lived in the Firmins' basement, and Professor Yaffle on Bertrand Russell, whom Postgate once met. Bagpuss himself was intended to be a more realistic ginger striped cat but a mistake with the dye proved to be a very happy accident.

It is not difficult to see the appeal of Bagpuss, even, perhaps especially, to supposedly cynical adults. First and foremost, Bagpuss is instantly loveable, with the permanent expression of a slightly surprised elderly gentleman, and the supporting characters are also likeable. Second, the show appealed unashamedly to nostalgia from the start, even before it acquired a nostalgic value of its own by being remembered so fondly years later.

That appeal to nostalgia operates on several levels. Like many great children's programmes, it is set in an idealised past, a Land of Childhood that has never existed. Any historian will tell you that growing up in the Late Victorian/Edwardian period in which Bagpuss seems to be set could be quite grim, but there is still an innocence to "long ago" lacking in more modern times.

The more universal nostalgia is that which most people have for their own individual childhoods. Surely only the dullest and most unimaginative child has never mind invested toys with personalities, and a well established storytelling device in which toys really do "come alive" has tapped into that to great emotional effect from Hans Christian Andersen to the 'Toy Story' films. Bagpuss is a particularly successful example of this long and distinguished tradition.

Rewatching the occasional episode can therefore bring a smile even to the hardened features of the most jaded adult. Moreover, it is as an adult that one better appreciates Postgate's subversive sense of humour. Thus, instead of the Princess kissing the Frog who then becomes a Prince, Gabriel the Toad tells the amphibian version in which the Frog kisses the Princess who does not want to be a Princess and who turns into a Frog. The Boney King of Nowhere finds his throne hard and cold - "uneasy lies the head that wears a Crown" transferred to another part of the anatomy, one more amusing to children.

Given the distinctively British, nostalgic, traditionalist, one might even say small-c conservative style of much of his work, especially Bagpuss and Ivor the Engine, it might be a surprise that Postgate himself dressed to the left politically. He was, after all, the grandson of George Lansbury, the Christian Socialist and pacifist who served as Leader of the Labour Party in the mid-1930s (incidentally, his numerous kin also include Dame Angela Lansbury and right of centre Past Prime Minister of Australia Malcolm Turnbull).

Postgate joked that Bagpuss was a Miaoist, and there has been speculation, of variable seriousness, that Bagpuss has a Marxist subtext. In this analysis, the Mice, who do all the work, but who have, with a couple of occasional exceptions, no individual identity, are the Proletariat. Madeleine and Gabriel, who are good at ordering the Mice around but who seem more interested in being arty than in actual work, are the Bourgeoisie. Yaffle is the Intelligentsia. Bagpuss himself is the Aristocracy, or perhaps a Constitutional Monarchy, deriving his primacy not from his contribution to the work, which is also not that great, but from the special favour of Emily - who may be a symbolic representation of God: she is invisible and takes no direct part in the drama of the individual episodes, but she starts everything off, she brings everyone to life with her words, she sets them their task, and her overall authority is generally acknowledged.

In the interests of political balance, it is also possible to subject Bagpuss to a Capitalist Critique. Since her shop has no income, how can Emily afford to run it? How does she pay the business rates on the property? We must conclude that she has other commercial interests sufficient to cover the costs of this unprofitable operation. Is Bagpuss & Co some sort of loss leader or a charitable write off against tax? Is Emily a deep pocketed philanthropist or an early Jeff Bezos playing a long game?

Perhaps one should not pretend to intellectualise about it, and just admit that one simply enjoys Bagpuss for its own sake. However, whatever one's own politics, it can be denied that in one respect at least Postgate was politically well ahead of his time: long before "Reuse, Repair, Recycle" became fashionable it was a major theme in Postgate's work, especially in The Clangers and here in Bagpuss.

For if Bagpuss has a Big Message it is that everything, no matter how dirty and broken it might appear, has a story and a use, and therefore has value - and since Bagpuss blurs the line between the animate and the inanimate, that is the same as saying that everybody has value. That is not a bad lesson for children - and adults too, come to that.

Like all lessons, it is most effective when it does not appear to be a lesson. Bagpuss is a sophisticated piece of art disguised as a children's story. Very few shows combine such a high degree of technical skill in all departments with such a high level of personal charm. The small number of episodes may have helped because, like Fawlty Towers, the quality never declined. Anyway, apart from anything else, who could resist that face? The closing words of every episode are enough to explain our lasting affection for Bagpuss: he may be "just a saggy old cloth cat, baggy, and a bit loose at the seams ...but Emily loved him." She is not alone in that.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on April 16th, 2021. Written by John Winterson Richards (with an incy wincy bit by Laurence Marcus) for Television Heaven.