Book Review: Seeing Things

SEEING THINGS

A MEMOIR - OLIVER POSTGATE

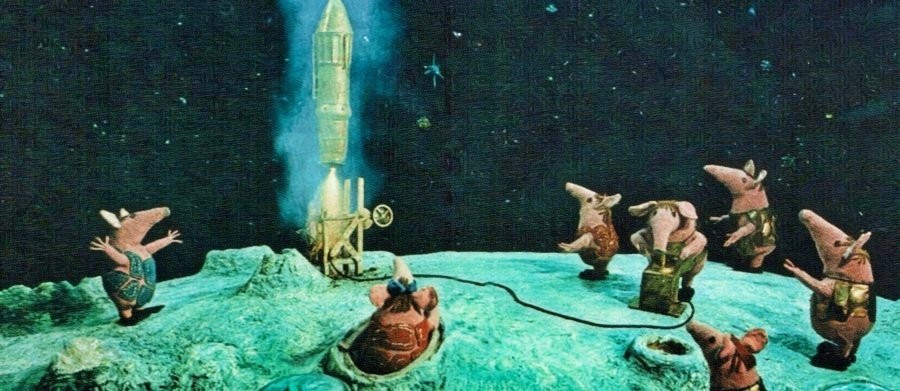

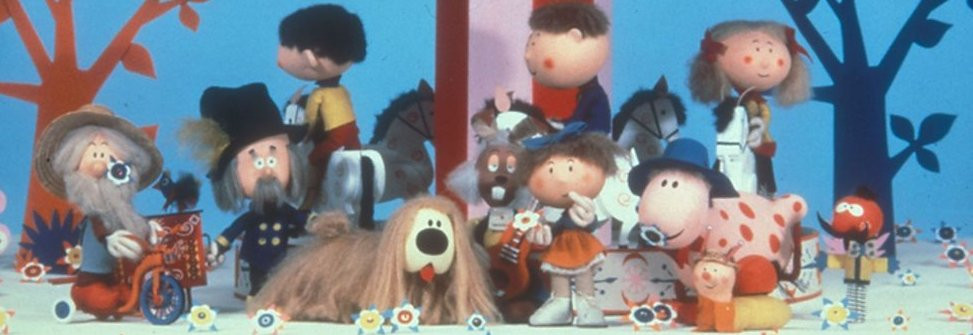

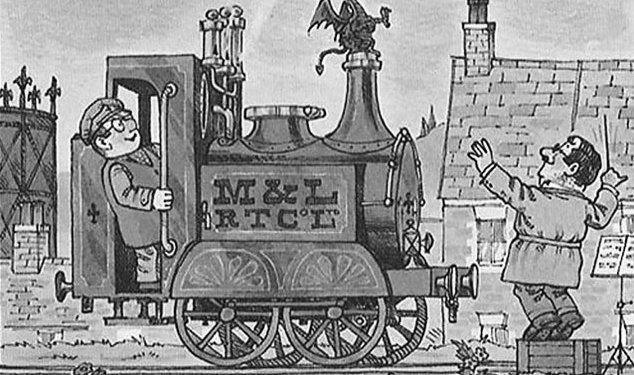

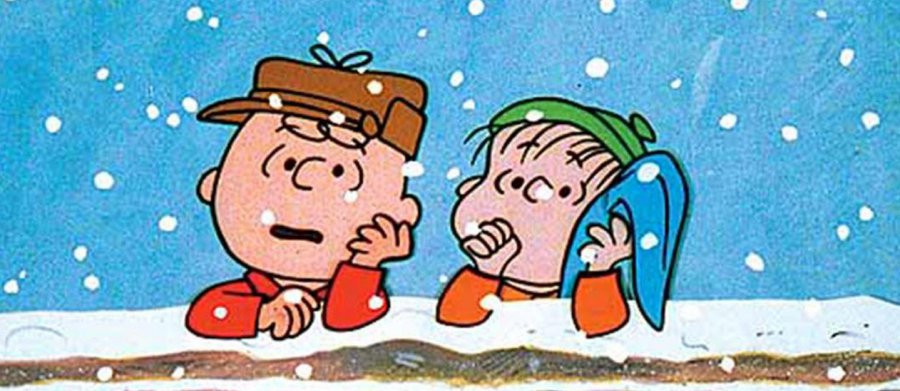

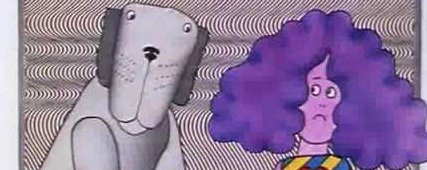

Children’s imaginations must be fed, should be shaped by positive and nurturing cultural forces. There is a generation out there, having had childhood foisted upon them during the late 1950s and through the following decade of the 1960s, that now smiles wistfully at the mention of Noggin, Olaf The Lofty and Graculus; Ivor and Jones The Steam and their daily adventures in that top left-hand corner of Wales; the yodelling Clangers and their Soup Dragon; and that saggy old cloth cat, the mouse organ and Professor Yaffle, the very distinguished old woodpecker. When Oliver Postgate, the uniquely British genius behind all these characters, died in December 2008 the grateful acknowledgement from the media industry and public alike was deeply affecting, none more so than Charlie Brooker’s very moving and poetic tribute on BBC4’s Screenwipe that same month.

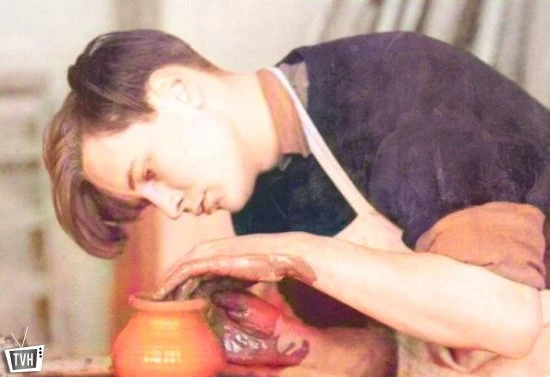

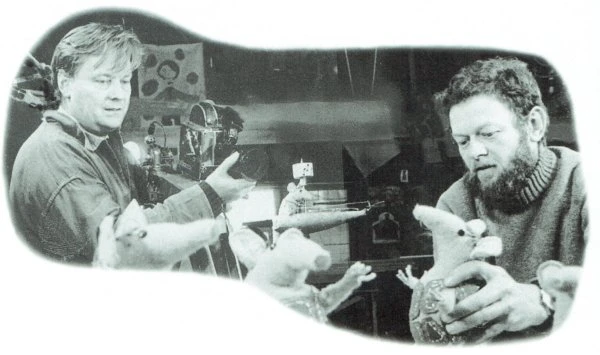

Smallfilms, the company that produced these films for children, came into being in 1957 when Oliver Postgate, then a stage manager at Associated Rediffusion and working in their children’s programmes department, set out to animate Alexander the Mouse using a crude magnetic process and backgrounds painted by Central School Of Art teacher Peter Firmin. 26 of these programmes went live-to-air and after struggling with the use of magnets to animate their characters, they made the move to stop-motion animation on film, originally using drawings and then later using puppets to bring life to such memorable creations.

The success of Alexander the Mouse and a film for deaf children, The Journey of Master Ho, allowed Postgate and Firmin to set up Smallfilms. Based in that studio in the now infamous, disused cowshed at Firmin’s home in Canterbury, Postgate wrote the scripts, animated puppets and provided both the narration and the voices for the characters and Firmin designed the characters and models. It’s Postgate’s charmingly surreal view of the world and his velvety narrations that continue to entertain, amuse and inspire audiences, adults and children alike, all over the world. And if nostalgia could be bottled then the output of Smallfilms, including Ivor the Engine (made in black and white for ITV and later in colour for the BBC in 1975), Noggin The Nog, Pingwings, Pogle’s Wood, Clangers, Bagpuss and Tottie all made between 1959 and 1984, would be considered of the highest, warmest, fuzziest vintage.

But how did Oliver Postgate arrive at Associated Rediffusion and then go on to influence generations of children and adults? In 'Seeing Things', Postgate’s memoir, originally published in 2000 and republished in 2009 with new foreword and afterword, respectively, by Stephen Fry and Oliver’s son Daniel, takes the reader on a fascinating, often very funny and very odd, journey from his own childhood to his work at Smallfilms and beyond. Postgate clearly struggled to find his niche in life and tried his hand at practically everything and was alternatively a farm labourer, an actor, an inventor, an artist and a relief worker in Brunswick in post-war Germany.

This meticulous memoir, beautifully observed, wistfully poetic and with a seam of honest self-deprecation running through it, immediately showcases the idiosyncratic, slightly off-kilter but thoroughly charming qualities that Postgate eventually encapsulated in his scripts for Smallfilms. It’s a rare synthesis of life experiences, self-obsessiveness and a particular way of thinking about the world that emanates from the pages of this book. His haphazard path through life, particularly his teenage and young adult years, although initially demonstrating that he was a person who found it difficult to stick with anything for very long, also suggested a creative spark simply in need of the right kindling to realise his burning ambitions.

The book is chock full of witty and extraordinary stories, highly descriptive passages that burst with light, colour, sound. His early childhood sees his mother Daisy aghast at the fact that he’s been stroking the backs of bees in their Hendon garden, his anxiety about the view from the top of a tram in the Finchley Road, and visits to the House Of Commons to see his grandfather, Labour leader George Lansbury, speak in the chamber.

His father Ray, who would become the founder of the Good Food Guide, and mother Daisy would take their children on culturally edifying trips abroad to Denmark and France. With the outbreak of war, as evacuees to Devon, Oliver and his brother John became day pupils at Dartington Hall School. Founded in 1926, the school was renowned for its progressive coeducational boarding life, its minimalist formal teaching and its success in educating the more wayward children of the fee-paying, liberalist intelligentsia of the late 1930s. It clearly left its influence on Oliver even if it didn’t leave him well equipped with the best tools for socialisation.

His own waywardness continued through to his enrolment at Kingston College Of Art. There’s a wonderful story where one day he decided not to get off the bus going to college and simply continued his journey, accepting fully the mystery of his eventual destination. He ended up sunbathing on Box Hill and he acknowledges that his view of the English landscape from the hill, poetically realised in the book, profoundly changed something inside him. In the Foundation Drawing Class at the college there is also another ‘eureka’ moment when his creative impulse forms all the proper connections and his ability to draw is fully realised.

There is also a Goon Show sketch like moment when he describes being called up to enlist in the Household Cavalry and arrived at the barracks determined to be arrested as a conscientious objector. Arrested in the most bizarre and quintessentially English manner, he eventually ended up in Wandsworth Prison. From there he tried various jobs including one as a general farm labourer. Meanwhile, the memoir demonstrates his inventive mind, keen to solve engineering puzzles, in a charming and hilarious passage about the Heath Robinson contraptions he built for his family - a washing machine with a life of its own, a high-speed food mixer and a bird-scarer that frightened the life out his aunt Emily.

By 1946 he’d joined the Relief Team of the Save The Children Fund in Germany and was doling out honey and cod-liver oil to desperate children in depressingly under-resourced orphanages. Returning from Germany in 1947, he joined LAMBA, convinced his career was in acting. His story about his role as a Chinese policeman, at £15 a week, in a production of Aladdin is again lovingly observed and very amusing. The inventor in him flourished again when he was employed as a designer to work on a set of interior showcases at the Festival Of Britain.

In 1957 he married Prue Myers after they both had to negotiate her divorce from her current husband which included arranging to be caught in flagrante delicto in a hotel room by a private detective. It’s at this point that Oliver started working at Associated Rediffusion as a stage manager and prop supplier (a collapsible soufflé, anyone?) and his career in making television programmes tentatively began. Through his friend Maurice Kestelman he met artist Peter Firmin, a lecturer at Central School of Art And Design and they worked together on the Alexander The Mouse transmissions.

And so the story of Smallfilms began and Postgate provides plenty of lovely anecdotes about the making of their various series together, with him generating the ideas and writing scripts and Firmin realising these visually. He recalled the BBC commissioning process as:

"We would go to the BBC once a year, show them the films we'd made, and they would say, 'Yes, lovely, now what are you going to do next?' We would tell them and they would say, 'That sounds fine. We'll mark it in for 18 months from now,' and we would be given praise and encouragement, and some money in advance, and we'd just go away and do it".

If only it was like that now.

After Smallfilms, he would increasingly devote his time to the campaign for nuclear disarmament and to environmental causes. Prue sadly died in 1982 but with his partner, historian Naomi Linnell, he completed several public art and publishing commissions in the 1980s. These included a 50-foot long tapestry Illumination of The Life and Death Of Thomas Beckett for Kingfisher Books and a mural for the University Of Kent. With Firmin (and Bagpuss) he was awarded an honorary degree by the University in 1987. Later, he blogged for The New Statesman, narrated BBC4’s Alchemists of Sound documentary in 2003 and in 2007 was the guest on Desert Island Discs.

After Postgate's death in December 2008, Smallfilms was inherited by his son Daniel Postgate. In October 2008, media company Coolabi bought the licensing and merchandising rights to Bagpuss, Ivor the Engine and The Clangers for £400,000, and declared its intention to revive Bagpuss. By 2009, Oliver’s son Daniel, declared that as Coolabi didn’t completely own the rights he would veto any revival of Bagpuss.

Quite right too. Nostalgia shouldn't be tainted by corporatist acquisition and any reader with a passing interest in Smallfilms will cherish the memories of Oliver Postgate in this beautifully written and illustrated book.

Review: Frank Collins

Frank is a freelance writer and film and television researcher. He has contributed to a number of books and websites about British archive television and cinema as well as recent television series including work for Moviemail, Frame Rated, Arrow Video and Indicator. Publications include The Black Archive #31: Warriors' Gate (2019), I.B Tauris's 'Doctor Who: The Eleventh Hour - A Critical Celebration of the Matt Smith and Steven Moffat Era' (2013) and 'Doctor Who - The Pandorica Opens' (2010).

Frank’s website is Cathode Ray Tube

Published on July 4th, 2021. Written by Frank Collins for Television Heaven.