Frank Herbert's Dune

2000 - United StatesFrank Herbert's 1965 Dune is one of the most influential science fiction novels of all time. It is not an easy read. The plot is a fairly straightforward 'bildungsroman,' a coming of age story in which a young man loses everything in order to gain everything - except that in this case, he goes out into the desert to find he has superpowers in another familiar trope, the "Chosen One" narrative. What makes Dune stand out among such stories is the depth of the imagined world in which these events occur and the breadth of the ideas which fill the book.

Indeed, it is the richness of ideas, rather than the basic storyline, that makes Dune as challenging as it is memorable. There are so many that there is bound to be a wide variation in credibility. Some are simply ridiculous. Others have not aged well, including the very Sixties notion of a mind altering substance being the gateway to expanded consciousness. However, there some that now seem particularly prescient - an important concept in Dune - most notably the importance of ecological systems: an imaginary planet where a very valuable product depends on a very dangerous creature which in turn depends on a very harsh environment has an obvious message for our world today.

Blending science fiction with mysticism, the novel asks some Big Questions, especially about the nature of Destiny: how can it ever be possible to see the future since seeing it will change it?

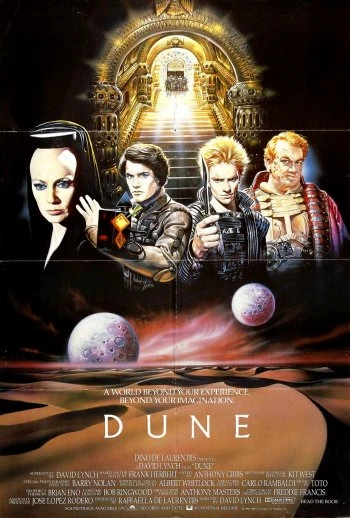

The problem with ideas is that they are notoriously difficult to dramatise and there are simply so many in the novel that it is impossible to fit them all in. David Lynch discovered this when he turned it into a feature film in the ominous year of 1984. Herbert himself gave the film his qualified approval because it tried to stay close to the book, but, from a more objective viewpoint, that was probably Lynch's biggest mistake, trying to keep too much of the detail of the book in a running time of only about three hours.

Even this was too long for the producers, who cut it to just over two hours. This reduced the narrative to a confused mess, heavy on exposition and reliant on the overuse of clumsy "voice over," setting up an interesting situation but then rushing to the end. The result was a predictable commercial and critical disaster.

It deserved better. Although it divides opinion to this day - some positively hate it while others positively love it - the fairest summation is that the film is a flawed masterpiece. Visually it has an epic grandeur almost unequalled in the science fiction genre - one really feels that the Universe is at stake - and the images stay in the mind long after the script is forgotten. There are lots of clever little touches not found in the book but typical of Lynch's slightly surreal imagination. The film also benefitted from a truly original soundtrack and a very strong international cast, some of whom made a very deep impression out of very little screen time.

It was that lack of screen time that made the Lynch film a glorious failure rather than the great success it might have been. One cannot help wondering what it would have been like as a television "miniseries" rather than a cinematic feature. An extra hour or two to let the story breathe and the characters develop - and the viewer get comfortable in an alien world - would have made all the difference.

Of course, the economics and technology of 1984 meant that the film's high production values could not have been replicated on television at that time. By the end of the 1990s, that was changing and advances in CGI began to make "epic television" a real possibility. As part of a risky new strategy of producing such content, Sci-Fi Channel gave John Harrison, a long time associate of George A Romero, his dream job of writing and directing Dune in a format that seemed made for it. The resultant "miniseries" is generally known as Frank Herbert's Dune, not least to distinguish it from the Lynch film.

Yet what strikes anyone familiar with the Herbert novel and the Lynch film most powerfully on seeing the Harrison "miniseries" is how often Harrison has made the same adaptation decisions as Lynch. To what extent this is deliberate only Harrison can say. Where their visual choices are similar, this is no bad thing, because the visual was where Lynch was strongest. However, it has to be said that Harrison also makes some of the same scripting mistakes as the film.

In particular, he tries to do too much, so that even four and a half hours is not really enough time. There is apparently a longer "Director's Cut," which might pace things out a bit better, but this is not the version generally available.

Although even the standard version is still very much an improvement on the structuring of the feature film, and the exposition is not so relentless, one cannot help feeling that the extra time could have been used more effectively.

One of Harrison's better decisions was giving more space to the female characters. The novel was ahead of its time in presenting several strong women who carried the story forward, but although Lynch respected this in some good casting decisions, he did not follow through in terms of giving his talented actresses much screen time.

Harrison does well to correct this. Saskia Reeves presents us with a fully rounded Lady Jessica, confident and assertive - perhaps because she has to be: she is uncertain of her status, first as a concubine to a Duke and then as a mother of a great leader determined to follow his own path. The part of Princess Irulan is expanded beyond even what the novel offers and Julie Cox rises to the occasion.

Overall, it is only to be expected that the "miniseries" cast is not of the calibre of the big names in the film and there is great variation in the standard of their performances, to put it politely. Although he is top of the bill, William Hurt brings little to the role of Duke Leto Atreides. It is not Alec Newman's fault that the script requires him to leap from spoilt brat to mature leader rather abruptly as the protagonist Paul Atreides-Muad'Dib. He does well in the latter part of his role, but by that time the former part and the rather unconvincing transition may have evaporated viewer sympathy for the character.

As the untrustworthy Emperor, Giancarlo Giannini looks both suitably untrustworthy and suitably Imperial. If P H Moriarty, best known as Razors in The Long Good Friday, sounds as if he has wandered in the wrong story, at least he looks the part as hardened enforcer Gurney Halleck and provides a bit of relief when the whole thing seems to be taking itself far too seriously.

Even more of that much needed relief comes from what is undoubtedly the outstanding performance in the project, by the splendid Ian McNeice as Baron Harkonnen. He does not hold back, going full pantomime villain, but not without making it very clear that this is a very intelligent and dangerous adversary. The whole thing is worth watching for his scenes alone.

Yet there is another, even better reason to watch Frank Herbert's Dune - the visual flair. Many of the sets and costumes are truly magnificent. If some qualification is necessary, it is that there is sometimes too much imagination. The Lynch film adopted a Ruritanian house style, with subtle hints of fascism, that made a definite impact. The message is clear: this is all about power. By contrast, the "miniseries" is all over the place and a few of the costumes, especially those worn by members of supposedly powerful and menacing organisations, are frankly rather silly.

The cinematography is marvellous, winning a deserved Emmy for Vittorio Storaro. The desert landscapes are the aspect of this production most likely to stick in the mind. Clever use is made of bright colour motifs. For example, the use of a bright red to denote House Harkonnen seems a deliberate evocation of a traditional image of Hell, with the wicked Baron as its Devil.

The "miniseries" also won an Emmy for its visual effects. It is only to be expected that this aspect of the production has not aged so well. The CGI which pushed the boundaries at the time now looks "very Nineties." The space scenes can resemble an episode of Babylon 5. The use of back projection is often annoyingly obvious.

Perhaps we should be more charitable. The "miniseries" was in its day a huge ratings success for Sci-Fi Channel, vindicating their new production strategy. This led to other "miniseries," most notably to a "reboot" of Battlestar Galactica and to Frank Herbert's Children of Dune, a direct sequel to Frank Herbert's Dune based on two of Herbert's subsequent novels.

Whether the "miniseries" was a dramatic success remains a matter of debate. One can understand if those unfamiliar with the books still found the story incomprehensible, and it is unlikely that it prompted many to read them. Among admirers of the books, there are three schools of thought: those who prefer the Lynch film; those who like the "miniseries" because they see it as improvement on the Lynch film; and those who dislike both as being untrue to what they see as Herbert's vision (which is something of an in-joke, since that is a big theme in his later books). All might agree that the definitive adaptation of Dune is yet to come. At the time of writing, another version - bravely, a feature film - is due to come out very soon. Whether it avoids the mistakes of its predecessors awaits to be seen.

Review by John Winterson Richards

John Winterson Richards is the author of the 'Xenophobe's Guide to the Welsh' and the 'Bluffer's Guide to Small Business,' both of which have been reprinted more than twenty times in English and translated into several other languages. He was editor of the latest Bluffer's Guide to Management and, as a freelance writer, has had over 500 commissioned articles published.

He is also the author of ‘How to Build Your Own Pyramid: A Practical Guide to Organisational Structures' and co-author of 'The Context of Christ: the History and Politics of Rome and Judea, 100 BC - 33 AD,' as well as the author of several novels under the name Charles Cromwell, all of which can be downloaded from Amazon. John has also written over 100 reviews for Television Heaven.

John's Website can be found here: John Winterson Richards

Books by John Winterson Richards:

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on February 7th, 2021. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.