Jessica Jones

2015 - United StatesThe cultural life of the 21st Century has so far been dominated by "multimedia" franchises. They have originated in film (Star Wars), television (Star Trek), and those big papery things full of words that old people used to read (Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings), but the rising power of the last two decades has been the American "comic book" franchise.

The best of these "comic books," and their more substantial cousins, "graphic novels," are indeed works of genuine artistic and sometimes even literary merit, but they developed on an ad hoc basis, most stories or series being essentially free standing. However, the publishers, most importantly Marvel (Avengers, Spider-Man, X-Men, Fantastic Four, etc) and DC (Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, etc), soon realised the potential of "crossover" editions, combining characters from different series. From there the idea developed that all a given imprint's characters were somehow part of the same fictional "universe."

Given their diverse origins, it is no surprise that these fictional "universes" are not very consistent, cohesive, or credible. A recent Amazon series, The Boys, has been very successful in producing a slightly satirical, but still oddly believable, picture of how a world overrun with "superheroes" might actually look. It is not pretty.

Marvel and DC had sold the film and television rights to their various series as they went along, sometimes quite cheaply, on the same ad hoc basis on which they had usually been written without any reference to their broader "universes." A number of free standing films and television programmes had been produced as a result, and Batman, Superman, the Hulk, Spider-Man, and Wonder Woman became well known to general audiences far wider than the readership of "comic books."

In recent years, however, heroic efforts have been made by intellectual property attorneys, above all those working for Marvel's Stan Lee, in clawing back those subsidiary rights or at least centralising them so that they could be used for united franchises involving the whole Marvel and DC "universes." The first hint of what was to come was at the very end of the 2008 feature film Iron Man, a successful free standing story in its own right, when Samuel L Jackson appeared in a post-credits scene and mentioned something called 'the Avengers Initiative' (not to be confused with the British television legend).

Well developed plans for sequels often look embarrassing in retrospect - note a similar mid-credits scene in Green Lantern which led nowhere - but what is now called "Phase One" of 'The Marvel Cinematic Universe' succeeded beyond what almost anyone might have dreamed. The cinematic releases of the whole franchise on their own have now generated total sales of over $20,000,000,000 at the time of writing. Marvel soon started ransacking their back catalogues for more material.

Even before the triumphant conclusion of "Phase One," it was intended to follow it up with television "spin offs" set in the same Cinematic Universe - which is quite different from the "Marvel Universe" of the original "comic books" - in order to broaden the multimedia franchise. Marvel Studios set up Marvel Television. Its first product was the respected Agents of SHIELD, in which a supporting character in the films became the leading character. Although not a great commercial success, it was generally liked, and ran for seven seasons on a major network, ABC.

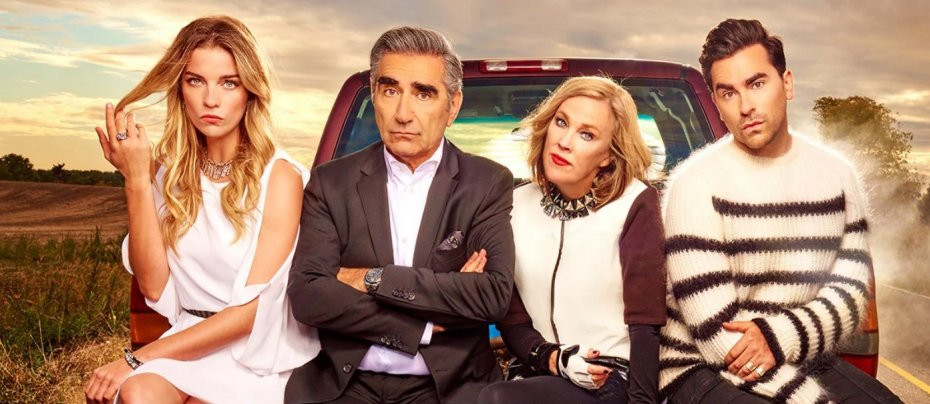

Meanwhile, Marvel concocted a very ambitious plan with Netflix for no less than five separate television shows, four based on individual characters from the Marvel back catalogues - Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Luke Cage, and Iron Fist - with all of them combining in the fifth as 'The Defenders.' Apart from Daredevil, the subject of a disappointing film, all were fairly obscure, but that was rather the point, because the five series together asked an interesting question: since there is only so much room at the top, what would life be like for those who were not celebrity "superheroes" in a world in which quite a lot of people had "superpowers"?

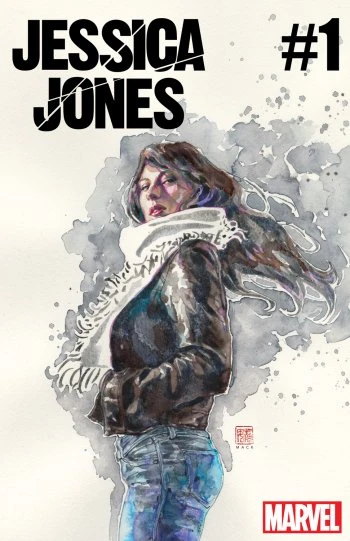

In the original "comic books," Jessica Jones is a second division hero, but was linked to most of Marvel's biggest names, including the Avengers, the X-Men, and Spider-Man. Most of this backstory is - wisely - junked in the Jessica Jones television series. Instead she becomes a downbeat private detective in the tradition of Marlowe and Spade who just happens to be freakishly strong and has the ability to jump long distances.

This is a good premise in its own right, and, to be honest, the references to other events in the Marvel Cinematic Universe seem unnecessary and are often inserted rather clumsily. The series would have worked better without them, but it was obviously felt it that was commercially more synergistic to maintain contact with the brand name. Stan Lee makes his traditional cameo appearance, as he does in all Marvel Cinematic Universe projects, but only on a poster, which rather sums up the status of Jessica Jones in the Marvel hierarchy.

Television Jessica is suffering from post traumatic stress disorder as a result of specific things that happened in her past which are referenced over the three seasons of the show itself rather than because she is a "retired superhero" as some sources claim. In particular, she was adopted as a publicity stunt by the grotesque mother of a child star after losing her parents, and later fell under the influence of a man named Kilgrave, who had the power to manipulate minds and used it to compel her to commit murder. This has all left her with a lot of psychological baggage.

She self medicates with alcohol and lives a lonely, seedy existence. She seems seriously intent on drinking herself to death. Until then, she runs a half speed detective agency, mainly to pay for her booze and the rent on her particularly drab, soulless office, where she also sleeps - it cannot really be called a home. Yet she turns out to be very good at what she does, and, again like Spade and Marlowe, her hard boiled exterior hides a very quirky, individual sense of honour and a susceptibility to compassionate impulse.

All this is delivered in a perfect 'film noir' style completely at odds with the usual aesthetic of the "superhero" genre. Indeed, for most of the time, the whole "superpowers" angle seems redundant. The show belongs in the detective genre more than science fiction, and as such it can be viewed as a tribute to the classic "gumshoe" films.

Of course, the big difference between Jessica and Sam Spade is that she is a woman - indeed, as portrayed by Krysten Ritter, a very thin, fragile looking girl. In "comic books" the female heroes tend to be well fleshed fantasy objects for the primary target market - young males - and generally give the impression that they work out a bit. Jessica's vulnerable appearance is therefore nicely deceptive - and not inappropriate for an alcoholic with an unhealthy lifestyle - setting up some enjoyable moments when she reveals her real strength.

Ritter's performance is the main reason to watch Jessica Jones, and it is worth watching just for her. She is magnificent, a flawed, relatable, realistic feminist hero for the early 21st Century. Ritter already had experience of playing cynical, sarcastic characters, mainly in comedy, most notably in the undervalued Apartment 23. She puts that well-honed specialist skill to good use in Jessica Jones, taking it to the next level by showing how the cynicism is just a facade, a wall erected to protect a woman whom life has hurt very badly.

Yet Ritter's is only one of several very strong performances by women. Rachel Taylor is charming as Jessica's adoptive sister, the former child star now looking, rather desperately, to find her role in the world: the subversive "flash backs" to her earlier life are particularly clever, even if her character arc is ultimately a poignant one. Her mother, Jessica's adoptive mother, is played by Rebecca De Mornay with such skill that we eventually find some sympathy, even perhaps a little respect, for a woman who at first seemed only monumentally selfish. Janet McTeer is a class act, as always, as Jessica's actual mother, and Carrie-Ann Moss is, for the first time in too long, given a part worthy of her talents as a ruthless attorney with the somehow appropriate name of Hogarth who sometimes hires Jessica as a private investigator.

This outstanding female cast rather overshadows the male side of the bill. Clarke Peters showed in The Wire that he knows how to do a sympathetic policeman but leaves too soon. David Tennant is wonderfully insidious as Kilgrave, the first season villain - his mental powers making him far more frightening than any strongman our hero has to overcome by simple brute force - but that only emphasises how Jessica's later adversaries are less threatening.

Indeed, there was a general falling off in the plot in the second and third seasons. There was also some uncertainty about the development of the character of Jessica. The whole point is that she is supposed to be a nonconformist maverick on the very edge of the law, and organised society in general, but on two separate occasions she is prepared to hand over people close to her to some very sinister authorities for unlimited incarceration in a secret place known only to be very unpleasant. It rather destroyed her image as a rebel who plays by her own rules.

Despite these flaws, Jessica Jones and Ritter deserved the critical acclaim they got, but that is not enough in the television business. The five Marvel Netflix shows never found their place in the Marvel Cinematic Universe as a whole, nor did any of them really take off on a free standing basis. The sad irony is that Jessica Jones had the potential to do so and might have done better, as a modern detective show, without the Marvel brand name and all that went with it.

Review by John Winterson Richards

John Winterson Richards is the author of the 'Xenophobe's Guide to the Welsh' and the 'Bluffer's Guide to Small Business,' both of which have been reprinted more than twenty times in English and translated into several other languages. He was editor of the latest Bluffer's Guide to Management and, as a freelance writer, has had over 500 commissioned articles published.

He is also the author of ‘How to Build Your Own Pyramid: A Practical Guide to Organisational Structures' and co-author of 'The Context of Christ: the History and Politics of Rome and Judea, 100 BC - 33 AD,' as well as the author of several novels under the name Charles Cromwell, all of which can be downloaded from Amazon. John has also written over 100 reviews for Television Heaven.

John's Website can be found here: John Winterson Richards

Books by John Winterson Richards:

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on December 4th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.