Strange Interlude

1958 - United KingdomComparatively few people had seen Strange Interlude when the BBC produced it for their 1958 series Television World Theatre*. The play, in which Eugene O'Neill unrolls the wide perspective of his characters' lives not only by the passage of conventional dialogue, but by the thoughts that pass through their minds as they meet, part and reunite over the years, presented a punishing challenge to theatrical performance. By 1958 the facilities at the disposal of television, permitted a production that was able to master the presentation without leaving an impression of experiment or trickery.**

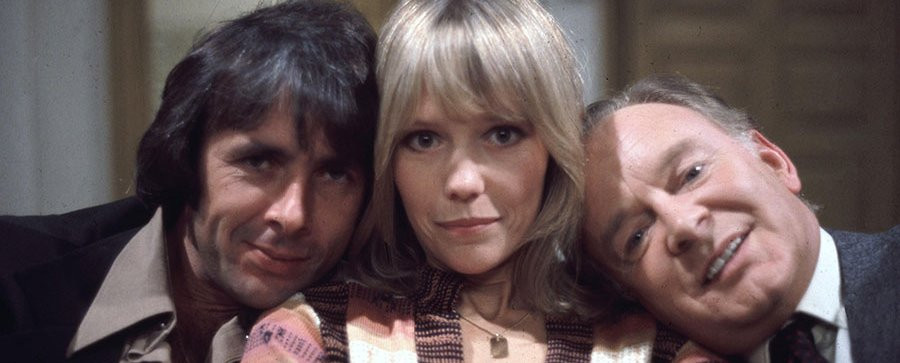

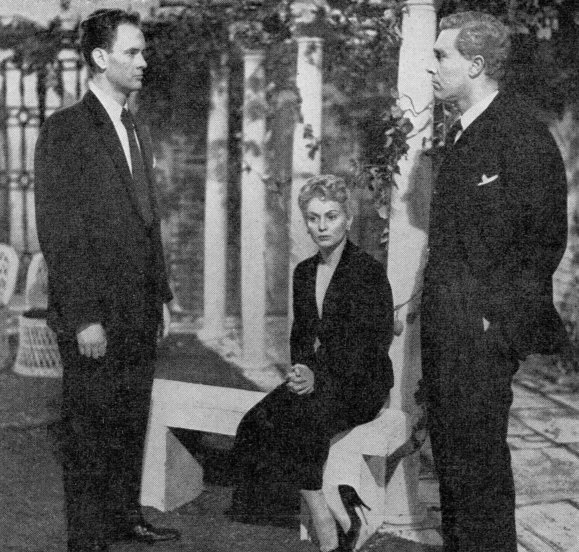

The play, in this BBC version, was three hours long in total and broadcast in two 90-minute parts. The first on Sunday 23 March 1958 and the second the following Sunday. In the first part of the play, Nina Leeds has married Sam Evans, only to hear from his mother that there is hereditary insanity in the family - a fact which Sam has never been told. Rather than Inflict this knowledge upon him through any children she might bear, Nina takes a lover, as the man who will be the father of her child, a friend of Sam's, Dr. Edmund Darrell. When she is expecting the child, however, she realises that she now loves Darrell and decides to tell Sam the truth. But Darrell, afraid of being further involved with her, breaks the news to Sam that Sam is to be a father. Nina realises that the trap is sprung. It is too late to tell the truth to her husband, and she has lost Darrell. The second act picks up the story twenty-years later.

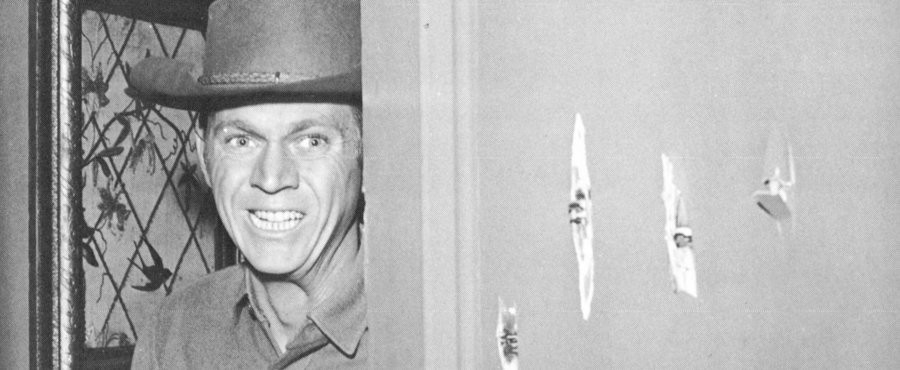

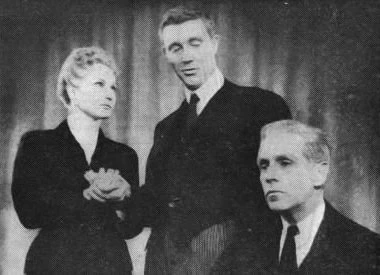

Diane Cilento plays Nina and producer John Jacobs specially flew to Rome to persuade her to come over and play this exacting role which covers a period of just over twenty-five years. Cilento agreed and came over to Britain to commence six weeks of intensive rehearsal. For David Knight (Sam Evans), who plays one of three men in love with Nina, acting in an O'Neill play was the fulfilment of a long cherished ambition. He told the Radio Times in 1958 that while he was in college in America O'Neill's work was very unpopular and he was alone in maintaining the genius of the Irish-American dramatist. In the five years following O'Neill's death (in 1953), there had been something of a revival of his work. The English and American theatre had rediscovered him. This posthumous fame transcended the success he had in his lifetime.

Born on 16 October 1888 in a hotel on the corner of Broadway, Eugene O'Neill was the son of an Irish immigrant actor. His father suffered from alcoholism and his mother was addicted to morphine. This perhaps explains why many of his plays involve characters on the fringes of society as they struggle to maintain their hopes and aspirations, but ultimately slide into disillusionment and despair. O'Neill himself suffered depression and alcoholism and in 1912 was admitted to a sanatorium to recover from TB. Upon leaving the sanatorium in 1913, he decided to become a writer. His later masterpiece, Long Day's Journey into Night is based on the events that led to his hospitalisation.

Strange Interlude, which he wrote in between 1926 and 1927, was an experimental play in nine acts. It opened on Broadway in 1928 and won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. It was also produced in London at the Lyric Theatre in 1931. The play was revolutionary in style and length, and at five hours its original production began in the late afternoon (5.15pm), paused for dinner, and resumed in the evening (7.40pm) at a time when most plays were beginning. In some theatres it was later performed on consecutive nights. The title is suggested by the aging Nina in a speech near the end of the play: "Our lives are merely strange dark interludes in the electrical display of God the Father!" Because of its controversial subject matter, in the USA the play was either censored or banned outside of New York.

Throughout the play, the characters alternate their spoken dialogue with monologues and side comments. It wasn't perhaps until the 1932 movie adaptation, starring Norma Shearer and Clark Gable, through means undreamed of by the playwright, that the tools he may have sought for the telling of his story, were fully realised. In the BBC version, producer John Jacobs (who in 1964 became Head of Drama at Anglia Television) chose to record actors’ thoughts as voice-over. The Times critic wrote that the transmission of the first part realised the play ‘for the first time in its proper medium. The interior monologue exploits the medium’s most potent asset – exact delineation of the act of thought’, and he also observed that ‘once the idiom had lost its experimental obtrusiveness one became aware of the variety of dramatic purposes it is made to serve; it acts as an ironic contradiction of the surface dialogue; as soliloquy; and it enables two characters with a secret to communicate in the presence of a third.’

This BBC adaptation of the play appears to differ somewhat from the original, especially in the relationship of the three characters. Nina, who is devastated when her adored fiancé is killed in World War I, embarks on a series of sordid affairs, ignoring the unconditional love of the novelist Charles Marsden, before determining to marry the genial but ineffectual Sam Evans. While Nina is pregnant with Sam’s child, she learns the horrifying secret known only to Sam's mother. Nina decides to abort Sam's child and conceive a child with the physician Ned Darrell, letting Sam believe that it is his. The plan backfires when Nina and Ned's intimacy leads to their falling passionately in love. Twenty years later, Sam and Nina's son Gordon Evans (played in the TV version by a young Richard O’Sullivan) is approaching manhood, with only Nina and Ned aware of the boy’s true parentage. In the final act, Sam dies of a stroke before he can learn the truth. This leaves Nina free to marry Ned Darrell, but she declines to do so, choosing instead to marry the long-suffering Charlie Marsden.

Ivor Brown in The Listener was full of praise for Diane Cilento’s performance, remarking that she ‘brought great intensity, as well as great beauty, to the agonising of Nina. But nobody, I fancy could wholly recommend the desperate lady to our sympathies. At times she is more tiresome than tragic.’

The message of the somewhat diluted BBC version is clearly an exploration of morals and consequences. In fact, the Radio Times informs us that ‘this is in the deepest sense a religious play.’ The play shows men and women in the very act of deception and self-deception. The relentless pursuit of happiness for Nina and others, sometimes selfish, sometimes bravely sacrificial, brings down terrible and tragic punishment on her. ***

Unusually for this period, the production was made as a tele-recording – shot as a live transmission it was preserved on 16mm film by a camera shooting directly at a monitor. As a result, it remains in the Archives and was shown at the BFI in 2015.

*Although the screen graphic showed the title as World Theatre it was billed in the Radio Times as Television World Theatre, a series that ran for three months.

**Daily Mail All Channels publication 1959

***Radio Times 1958

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on February 23rd, 2021. Written by Malcolm Alexander for Television Heaven.