The Lone Ranger

1949 - United StatesThe Lone Ranger galloped into American hearts long before he ever appeared on television. First brought to life over the airwaves in 1933 by Detroit radio station WXYZ, the masked lawman was the creation of station owner George W. Trendle, producer James Jewell, and prolific writer Fran Striker. The radio series quickly became a national phenomenon, spawning film serials from Republic Pictures before making its landmark leap to television in 1949—where it would become one of the first true hits of the small screen and a defining icon of American Western mythology.

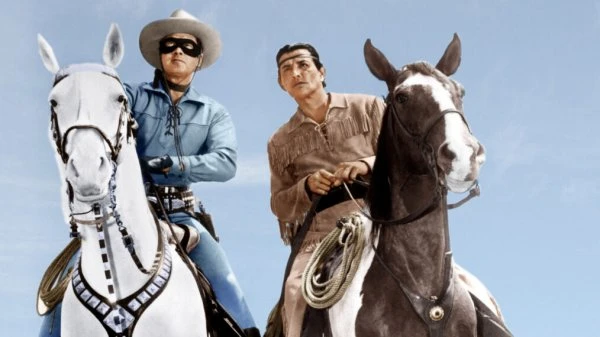

The television debut introduced audiences to the origins of John Reid, one of six Texas Rangers ambushed by the Butch Cavendish gang. Left for dead, Reid is nursed back to health by a Native American scout named Tonto, who solemnly informs him: “You only ranger left. You lone ranger now.” Thus begins a lifelong quest for justice. Donning a black mask, a crisp white Stetson, and astride his white stallion Silver, the Lone Ranger rides the frontier with Tonto at his side, fighting corruption wherever it rears its head and restoring peace before disappearing into the sunset to the cry of “Hi-yo, Silver – away!”

As Westerns go, The Lone Ranger was less gritty realism and more moral parable. The show operated under strict production guidelines: the Lone Ranger never shot to kill, always spoke in perfect grammar, and stood for nothing less than the civilised development of the American West. Parents loved its patriotic overtones and emphasis on honour, fairness, and restraint—so much so that even J. Edgar Hoover described it as “one of the forces for juvenile good in the country.”

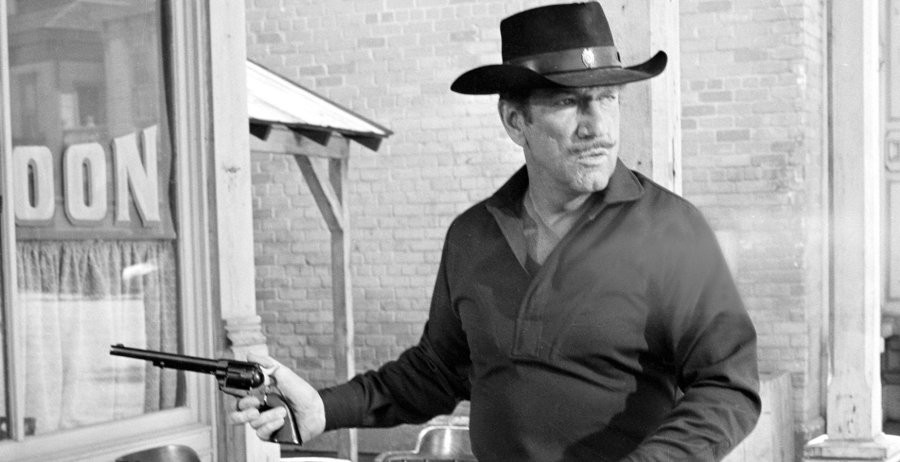

Clayton Moore, a former trapeze artist and male model, became inseparably linked with the role of the masked man. Although briefly replaced by John Hart during a studio dispute, Moore returned to the role that made him famous, while Hart found later success elsewhere, including Hawkeye and the Last of the Mohicans. Tonto, portrayed by Jay Silverheels—born Harold J. Smith and a true Mohawk by heritage—was a loyal companion, although years later Silverheels criticised the way Native Americans had been stereotyped in film and television, including in roles like his own.

Beyond the iconic duo, the series introduced a small cast of recurring characters, such as Dan Reid, the son of the Lone Ranger’s murdered brother (and, in a clever twist of continuity, future father of The Green Hornet, another Trendle creation), and Jim Blaine, who managed the Ranger’s privately owned silver mine—a source of both income and an inexhaustible supply of silver bullets.

The series' appeal was immediate and enduring. With its rousing use of Rossini’s William Tell Overture, fast-paced plots, and clearly drawn moral lines, it presented a version of the American West scrubbed clean of historical ambiguity—a mythic land where right and wrong were easily distinguished and justice could always be achieved by a man with a strong jawline, impeccable grammar, and a white horse.

In truth, The Lone Ranger was far removed from the complexities of the real frontier. Its characters were largely static, its stories formulaic, and its depiction of Native Americans deeply outdated. Yet, it offered audiences of the 1950s a reassuring fantasy of order, honour, and the triumph of good over evil.

In Britain, the series enjoyed a modest following, though it never reached the same cultural heights as in the U.S. Perhaps it was simply too American in tone—too earnest, too morally upright, too saturated in frontier nostalgia. Still, as a relic of its era, The Lone Ranger remains an intriguing testament to the power of television to mythologise history and create enduring heroes. A true product of its time, it gallops on in the collective memory of generations who once believed that, with a mask and a silver bullet, the West could be won.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on December 31st, 2018. Written by Skip Wilson Jr. for Television Heaven.