The Year of the Sex Olympics

1968 - United KingdomConcerned by overpopulation and what he saw as the counterculture of the 1960s, which he confessed that he hated, writer Nigel Kneale set about writing one of the most controversial plays of the decade. One that 'Clean-Up TV' campaigner Mary Whitehouse unsuccessfully tried to ban before it even got to the production stage. The play, shown in 1968, foreshadowed the rise of reality television over thirty years later and, despite being criticised as 'too fantastic' when originally shown to a marginal audience, is now regarded as something of a classic.

Nigel Kneale was already established as a writer of classic television. After joining the BBC in 1951 as a staff writer (one of the first to be employed by the Corporation), his first major success was The Quatermass Experiment, broadcast over six half-hour episodes in 1953. Initially critical of the BBC's television output, which he thought slow and boring, his Quatermass series raised the bar by offering a science fiction story that was distinctly new and full of intrigue, action and horror. Audiences were captured. The following year his adaptation of George Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, directed by the Austrian Rudolph Cartier, caused even more of a stir, with questions being asked in Parliament about whether some of the more shocking scenes were suitable for television.

After writing Quatermass II in 1955, Kneale left the BBC to turn freelance and following his last Quatermass serial in 1957 (Quatermass and the Pit), spent the next few years concentrated mostly on movie screenplays. In the spring of 1964, he proposed a single 150-minute 'anti-youth' drama to the BBC, which was titled The Big Giggle, and concerned itself with a wave of teenage suicides. The BBC commissioned the play (as The Big, Big Giggle) before having second thoughts (or 'getting cold feet' as Kneale himself later recalled), and worried that it might encourage real life imitators, cancelled the project. Kneale later admitted that it was the right decision.

Instead, Michael Bakewell, the producer of BBC2's Theatre 625, commissioned Kneale for a play under the title of The Year of the Sex Olympics. Kneale saw it as a statement on the then trend of 'free love' and 'dropping out' and how it could be stopped from undermining society in the future. His vision was of a society fed, warmed and protected from its own impulses and kept to manageable numbers, not by war or disaster or culling, but by 'gentle discouragement' and by, in his own words, "flooring it with vicarious experiences, particularly sexual. Television and pornography in ultimate combination."

Kneale's bleak look at the future hypothesized a society that was divided into 'low-drives' (the labouring classes) and 'hi-drives' (who control the government and media). The hi-drives are sexually active and work their way through a string of relationships. Any children born as a result are then offloaded, to be raised by the Child Environment Centre prior to being classified as 'high' or 'low.' The thoughts of the 'low-drives,' who form 98 per cent of the population, are controlled by a constant stream of television, which totally dominates their world. There are gluttony programmes designed to put people off food, and applied pornography programmes to put them off sex. There's art-sex, and sport-sex. All this happens in the year of the Sex Olympics.

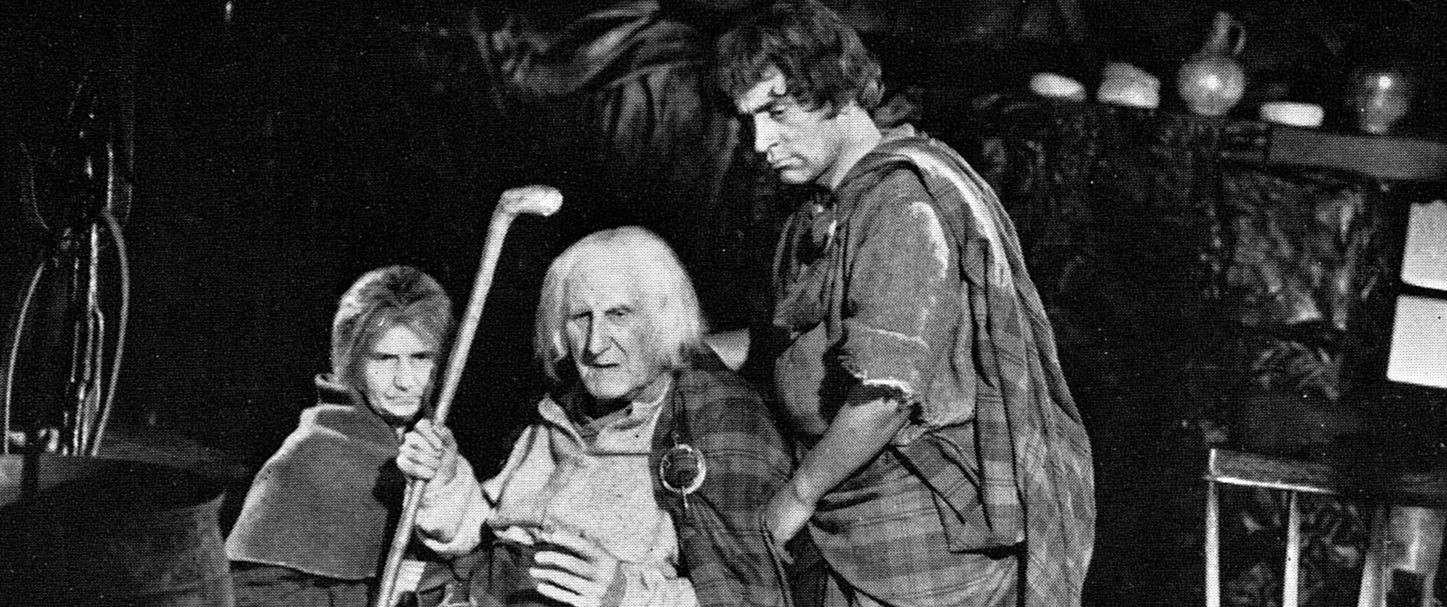

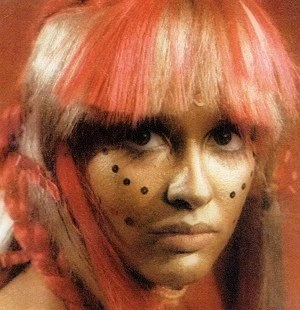

Language has become almost redundant and words such as war and love have been completely eliminated. But for a tiny minority who want no part of television there is one way out: To become a programme themselves. Deanie Webb (Suzanne Neve), Nat Mender (Tony Vogel) and their child go to a small Scottish island where life has been made trivial and safe, is not comfy and cosy, and where television does not supply all their needs. The cameras are on them 24/7 on 'The Live Life Show', a concept devised by the co-ordinator Ugo Priest (Leonard Rossiter), which soon becomes top of the ratings. The final outcome is both tragic and terrifying.

Viewer reaction to the play was somewhat disappointing. An audience of around 1.5 million tuned in to watch it but an Audience Research Report for the play returned verdicts of 'too fantastic', 'unnecessary violence', and 'an appalling view of a television dominated future'. Critics were more favourable towards it. Nancy Banks-Smith writing in The Sun noted: "Quite apart from the excellent script and the 'big big' treatment, the play radiated ripples. Is television a substitute for living? Does the spectacle of pain at a distance atrophy sympathy? Can this coffin with knobs on furnish all we need to ask?"

The play was shot in colour but after the master tape was wiped it was believed lost for many years. Then, in 1980, a complete copy of a 16mm monochrome film recording was discovered. Given a welcome release by the BFI in 2003 under their Classic Television banner, with a commentary track by actor Brian Cox, the play prompted Paul Hoggart in The Times to write, "in many respects Kneale was right on the money."

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on November 28th, 2020. Written by Marc Saul for Television Heaven.