Watership Down

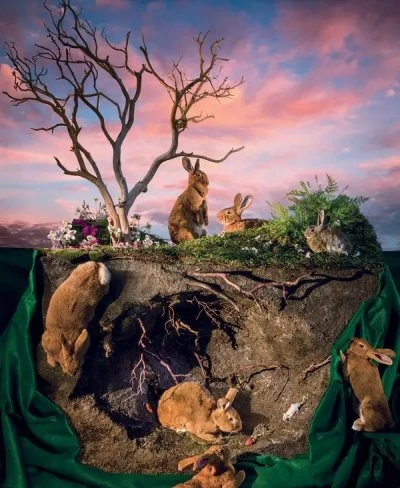

2018 - United KingdomSometimes dismissed as a "children's book," Richard Adams' novel 'Watership Down' is in fact one of the high points of 20th Century English literature. It references a wide reading of earlier classics, explicitly in its use of epigraphs and more generally in the structure of its story. Its lyrical descriptions of the countryside are as evocative as the poetry of Wordsworth. While its use of the perspective of talking animals was by no means original, it transcended the genre of 'Black Beauty' and The Tale of Peter Rabbit' by giving rabbits a sophisticated culture of their own. Others have observed, with great perception, that it has more in common with "Big Map Fantasy" like Tolkien's, a genre in which Adams was later to dabble with some success, than with "kiddie-lit." The difference is that the map in 'Watership Down' is a real one of an actual district of rural North Hampshire. An imaginary world of animals was overlaid on the existing human world. It was a truly brilliant concept, executed brilliantly.

At the same time it still serves the most important function of children's literature, in that it introduces them to adult concerns, not least the difficult topic of death.

Martin Rosen understood this in his beautiful 1978 film adaptation of the novel. He did not hold back on his accurate depiction of Nature as red in tooth and claw, not least when that bloodiest of animals, homo sapiens, is involved. This did not prevent the film being a huge critical and commercial success, as it deserved. It was only in retrospect that we were told that it was "the film that traumatised a generation." Really? Speaking as one of that generation, it took a great deal more to traumatise children back then than it might today.

It seemed particularly ridiculous that a television showing of the film a few years ago attracted complaints that it was unsuitable for Easter! The people making those complaints were evidently as ignorant of the novel and its meaning as they were ignorant of the significance of Easter. Indeed, one might wonder if Adams, a thoughtful Christian, was trying to link the two in the death, resurrection, and eventual ascension to Heaven of the self sacrificing leader figure.

The reaction against the brutal honesty, or perhaps honest brutality, of the novel was well underway by the turn of the Millennium when a three-season, 39-episode television "spin off" was aimed squarely at the children's market. It was toned down considerably and departed a long way from the book, so hard core Adams fans tended to avoid it. Since your reviewer is just such a fan, this episodic series is not the one being discussed here.

This is instead a review of the "miniseries" based directly on the book made a generation later. It seems an odd artistic and commercial decision on the part of the BBC and Netflix to spend a significant eight figure sum to go head to head with an acknowledged classic, which is what the Rosen film has become in its own right. The same can, of course, be said of many recent remakes. One suspects it is no more than a desire to squeeze money out of a familiar name, but there is a case for saying that any classic should be subject to constant reinterpretation, and that the Rosen film, the episodic children's show, and the "miniseries" each says something about their respective generations.

If so, what is says about the current generation is hardly complimentary. The 1978 film is superior in almost every point - storytelling, animation, cast, understanding of the source material, soundtrack, character development, etc, etc. Yet, if one can get over that, and assess the "miniseries" on its own terms, as if the Rosen film did not exist, there is still much to commend in it. The problem, as will become clear as this review goes on, is that, love it or hate it, the Rosen film is hard to forget and comparison keeps popping back into the mind. The producers should have known that when they decided to spend all that money. This does not negate the fact that, viewed objectively, the "miniseries" is a truly outstanding production.

First and foremost, it is a great story with great characters. However, it has to be said that Adams must take the credit for that and the "miniseries" is at its strongest when it stays closest to his original concept. It is at its weakest when it tries to bring it "up to date." This is always a mistake. So Hazel becomes plagued with fashionable self doubt, while Bigwig has been turned into a thuggish character who contests his leadership aggressively - until he just stops. This misses the whole point of the subtle relationship and growing respect between them that is one of the great themes of the book. Another important character is developed in what seems to be an interesting direction until he is suddenly thrown away in a casual fashion more irritating than tragic. The writing is too often "on the nose," saying something aloud, even flogging a point to death, rather than bringing it out in the story. At the same time, despite taking more than twice as long as the Rosen film, several themes and subplots remain underdeveloped.

Some of the updating is justified. In particular, there is a greater role for the female rabbits. This is not about feminism or so called "political correctness." Adams himself, as both a man and a writer, had a particular interest in the perspectives of women, and seems to have been genuinely mortified by criticism of the fact that nearly all of his heroes in 'Watership Down' are male - especially when it was pointed out that does are more likely than bucks to leave a crowded warren in order to start a new one. He tried rather clumsily to make up for this in a sequel collection of short stories, 'Tales From Watership Down.' The "miniseries" addresses the issue sensibly in a less confrontational manner which is actually an improvement on both the earlier and the later Adams in this respect.

If the story takes a while before it really begins to grip, things get a lot better once we reach the totalitarian warren of Efrafa. The "miniseries" is not as subtle as the novel in making obvious political parallels with the 20th Century, which is not a bad thing.

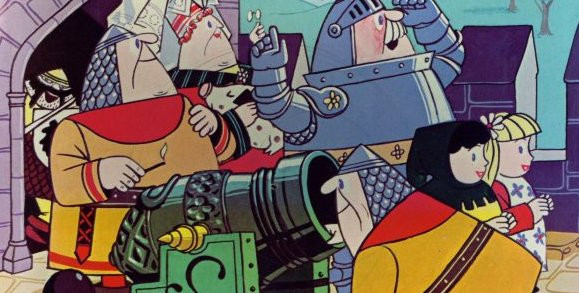

Where the animation of the Rosen film is self consciously artistic - a book of stills from the production is an aesthetic treat in itself - the "miniseries" aspired to a more realistic style. As such, it succeeds. If some scenes smack a little of the computer, others are accurate representations of the British countryside which evoke a definite sense of the joy and wonder of Nature.

The "miniseries" rabbits are certainly a lot more realistic than Rosen's - even if they sometimes seem more like realistic hares than realistic rabbits. It must also be asked if there is such a thing as being too realistic when it becomes difficult to tell the characters apart.

The landscapes are delightful and the set pieces work well. There is a sense of scale that was sometimes missing even in the cinematic version. The siege of Watership Down is truly epic. If you assume there could never be anything menacing about a line of rabbits coming over the hill, you would be wrong.

One suspects that Adams, who passed not long before production began, would have enjoyed this aspect very much. Classical masters of the epic like Homer and Xenophon were obvious influences on the novel and his work in general.

The soundtrack is forgettable, but then how could one ever think of 'Watership Down' without the score for the Rosen film beginning to play in the mind, complete with Art Garfunkel singing 'Bright Eyes'? Indeed it might be an interesting experience to watch the visual images of the "miniseries" with the sound turned down and the 1978 soundtrack on in the background.

In much the same way, the vocal performances do not stick in the mind as well as the echoes of the voices in the Rosen film. That said, it is nevertheless a very strong cast. Sir Ben Kingsley gives his usual authority to General Woundwort, the terrifying Tyrant of Efrafa. Olivia Colman brings personality, as well as a sex change, to the nervous Strawberry. In a nice reference, Rory Kinnear, whose father Roy played a different character in the Rosen film, is the urbane Cowslip.

Other familiar names include James McAvoy as Hazel, John Boyega as Bigwig, Nicholas Hoult as Fiver, Peter Capaldi as Kehaar the Seagull, Tom Wilkinson as the Chief Rabbit, Gemma Arterton as Clover, James Faulkner as "Frith" (the Lapine concept of God), Rosamund Pike as the Black Rabbit of Inle (the Lapine Angel of Death), Taron Egerton as El-Ahrairah (the First Rabbit), Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Mackenzie Crook, Anne-Marie Duff, Henry Goodman, Peter Guinness, Jason Watkins, and Gemma Chan. If the dramatic impact of this distinguished cast is less than the sum of its parts, one cannot help wondering if its very distinction worked against it: perhaps too many of these busy actors had to be recorded separately. It would explain a lot.

It is also frustrating that some are not given much time to develop their characters. Of course, screen time is limited in any production and choices have to be made, but one of the better pretexts for the remake is that the "miniseries" format should give more time to include things that had to be left out of the feature film and that is what did not happen. Given the precious gift of room to expand the story, the script did not use it particularly well.

The overall result is still a powerful and moving drama, and if it lacks the full emotional punch of the novel and the Rosen film, that is to be expected, because so does almost everything else ever written.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on September 9th, 2021. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.