The Fantastic Adventures of 4-T

1984 - United KingdomReview by John Winterson Richards

The most surprising aspect of having written about 300 different television shows reviews and articles on this website is the realisation that one has actually watched all or substantial parts of so many - and more - over the course of the last few decades. To be honest, not all of those 300 were strictly speaking television shows, even if all were viewed on a television screen. Some, including Bandwagon and Misery Bear, are more accurately described as web series. Then there is The Fantastic Adventures of 4-T, which could only be viewed on television, and which was a great deal more entertaining than most television shows proper, but which was still essentially no more than a few pages of computer text.

Teletext is, like the Hovercraft, Concorde, the Harrier VTOL jump jet, and the Sinclair C5, another of those distinctly British inventions that were generally admired, at least in principle, but not generally adopted abroad as the inventors had hoped.

It is perhaps difficult to convey to the internet generation how difficult it used to be to access hard data at will unless one happened to be hooked up to expensive networks that were really the prerogative of big media and other business organisations. Teletext was therefore for many businessmen, including this one, the main source of relatively up to date information on what the markets were doing. Providing rapid and comprehensive sports results was essential to another class of gambler. Teletext was also the only place you could find the latest details of election results and other current affairs in between different printings of newspapers. Even with the advent of 24-hour television news one had to wait for the relevant report to air, and then it was usually superficial. With teletext you only had to type in three numbers and then usually let it work its way through a few pages before getting precise figures you needed.

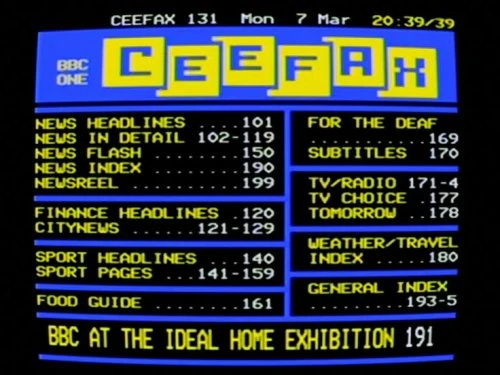

The BBC launched Ceefax, its definitive teletext service, as early as 1974. As well as being the first, it was the best and the longest lasting, only being switched off in 2012, years after the internet had effectively made it redundant. Its news coverage was excellent. Forced by its technological limitations to become very good at what they did, its nameless writers developed the journalistic art of summarising complicated stories in a few short paragraphs almost to perfection. Although they were not free of the usual BBC prejudices and obsessions, their reporting was generally very fair, more so than that of the more prestigious radio and television newsrooms, the pressure to exclude superfluous words probably working in their favour in this respect.

ITV launched ORACLE, its competing teletext service, in 1978. ORACLE also had the teletext contract for the new Channel 4 when it launched in 1982. This Channel 4 subsidiary was named 4-Tel and ran until ORACLE lost their contract to an inferior provider in 1992.

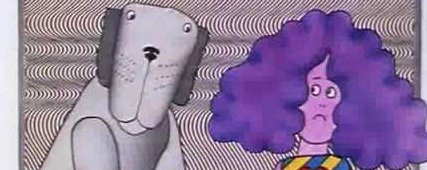

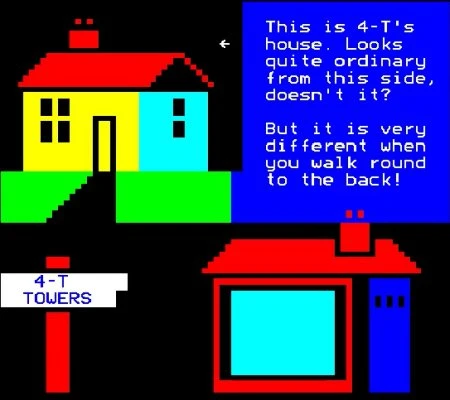

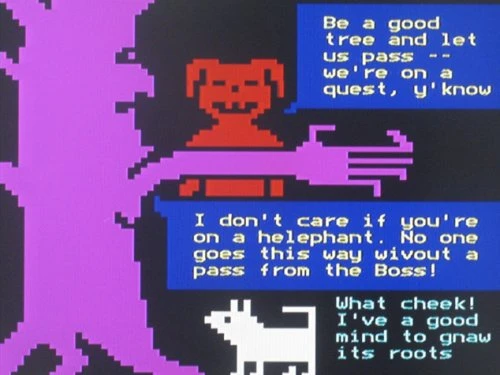

It was always part of Channel 4's remit to be a little bit different, even eccentric, which was probably why the decision was made to include a few pages of what was ostensibly a children's comic strip. This was The Fantastic Adventures of 4-T, the eponymous 4-T being a cartoon dog named after the 4-Tel service itself. It is sometimes cited as "The Fantastic Adventures of 4-T the Dog," but this is inaccurate: 4-T was always just 4-T; it was unnecessary to point out that he was a dog because his doggishness was so obvious that it required no emphasis.

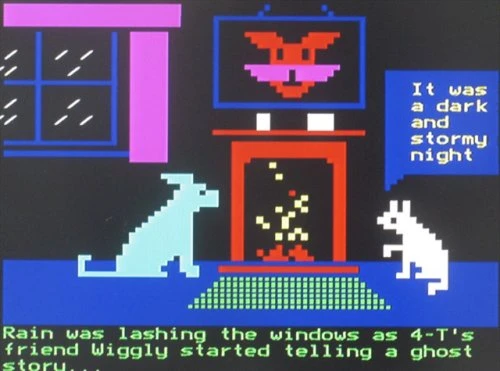

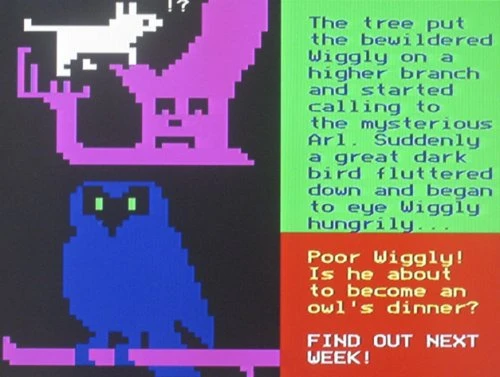

The concept was basically a British children's comic of the 1970s transferred to a television screen using the limited computer graphics of the time, relying on what now looks like a very small number of very large pixels and a palette of a very few, mainly bright and primary colours. Therein lies much of the charm.

It was the work of Ian Irving, described as "the first teletext art superstar" by a leading teletext art website - yes, there is such a thing, and it turns out to be an interesting discipline in its own right. Like the teletext news writers, Irving was forced to get very good at what he did by the limitations of the technology with which he had to work. One might even draw an analogy with poetry, or any other art form that imposes restrictions on the artist, in that it is the restrictions themselves that enable him to demonstrate his true artistry in overcoming them.

Irving had worked with the team that had developed Ceefax, so he was already a skilled graphic designer, but the real joy of The Fantastic Adventures of 4-T is seeing how he is constantly finding new ways to convey the personalities of his characters with those few pixels and colours. They are far more expressive than they have any right to be.

If characterisation is the great strength of The Fantastic Adventures of 4-T, plotting is more of a weakness. The whole premise is that 4-T is a dog who goes on weird adventures with his friend Wigglesworth or "Wiggly," who might or might not be a mouse - even the narrator is not sure. In the course of these adventures he makes other friends, including Cindy the Spider and Vince the Valve, who often turn up in later adventures too. By Irving's own admission, he tended to make stories up as he went along, leaving them to find their own course. They usually did, except that the endings were often rather abrupt and contrived when he reached the end of a fixed term run of several weeks with no plan how to tie everything up.

This did not matter too much since hardly anyone followed 4-T for the stories. A new episode of 4-6 pages would be put up, replacing the old one, every week for up to twelve weeks, which was usually the full run of an individual story, so it is a fair bet that anyone watching the final episode had already forgotten the first and much more of what had gone before. This was in accord with the tradition of British children's comics which, unlike like their American counterparts, were not generally collected and kept.

The slightly surreal sense of humour in The Fantastic Adventures of 4-T also seems to owe a lot to those Seventies British comics. There is a Pythonesque subtext to the whole thing. Many of the funniest moments are in the details, especially throw away lines or thought bubbles independent of the main narration. This harks back to classic Georgian cartoonists like Gilray and Cruikshank.

Given this level of sophistication, one wonders how many actual children followed The Fantastic Adventures of 4-T. One suspects its greatest devotees were students and stockbrokers, the former switching on teletext when coming in slightly sozzled, the latter idly flicking through pages while pretending to watch the market prices. Whoever it was, 4-T became a minor "cult" item at the time and is today probably the aspect of teletext remembered most fondly.

This is not saying much because teletext in general seems to be slipping from the popular memory. It was always by its nature ephemeral, but it was important in its time, and someone should preserve it as part of our cultural history. Irving himself has put a few of the stories he found on his old "floppies" up on a website, but they represent only a fraction of the 2,500 pages he estimates that he produced over ten years. The thought occurs that the best of them would actually make great children's books, which could in turn be the basis of a better animation than many being produced for television these days. In retrospect it seems incredible that no one thought to do so while Bernard Cribbins was still with us. It would be a guaranteed classic.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on February 7th, 2025. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.