Misery Bear

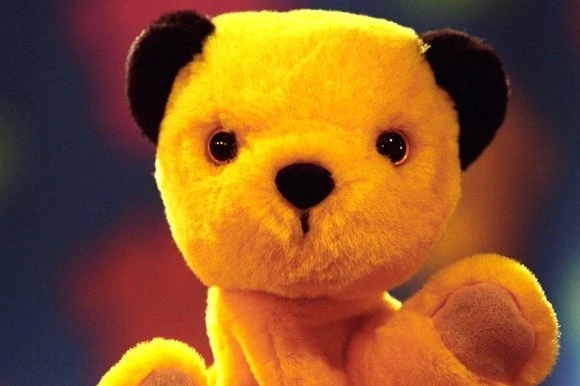

2009 - United KingdomYoung men are simply not loveable. Teddy bears are.

Misery Bear review by John Winterson Richards

One of the many joys of writing for Television Heaven is that it provides a platform to draw attention to relatively obscure shows that truly deserve a much higher profile. Sometimes, as a reward for my faithful service, our Editor allows me to go a bit off piste. So my 100th review a few years ago was of a television show, Bandwagon, that was not strictly speaking a television show, because it was never broadcast or streamed by a major service: instead it offered the opportunity to draw attention to some of the exciting things happening in "micro web series" and how the boundaries between media are getting increasingly blurred.

As a further example of that blurring, Misery Bear is something of a hybrid, a broadcast quality comedy from one of the biggest broadcasters in the world, the BBC, that was never intended to be broadcast. It was instead simply put up on their website in 2009 and left there. It was given very little publicity, so few people found it, and then mostly by accident. A high proportion of those who did, thought it much better than most of the actual broadcast comedy being made at the time, which was, it has to be said, not exactly a "Golden Age of British Comedy."

That Misery Bear the show was, and continues to be, unfairly overlooked and neglected is a sad irony because its whole premise is that the same is true of its protagonist and title character.

The loveable loser is a well-established trope in British television comedy - not so much in more aspirational American television comedy, it should be noted. The trope was simultaneously revived, satirised, and exploited to great success by Miranda, starting around the same time as Misery Bear.

What makes Misery Bear unique among these well-meaning failures is that he is a teddy bear - a literal teddy bear, not a metaphorical one. A few inches high, he is usually being moved by a hand just out of shot, just as children play with their stuffed toys, but there are some clever sequences where he is seen moving full figure. Sometimes he interacts with other teddy bears but mainly with human beings. He and the other bears act like humans in every respect, except for the fact that they cannot talk, and they are treated no differently from humans by the actual humans.

There is therefore one basic joke that runs all the way through Misery Bear, that a teddy bear, the symbol of childhood innocence, is seen doing all the squalid and seedy things associated with young manhood in modern Britain. He drinks heavily, he is bored by a pointless office job, he eats fast food, he throws up a lot, he tries very clumsily to pick up women, and he looks at internet pornography.

This may prompt those of us with a few more miles on the clock to reflect on how little time passes in the broad scheme of things from being a child playing with teddy bears to assuming the supposed rights and responsibilities of adulthood with all that involves. It is only a few years, and this at a point in life when young people are still growing physically, mentally, and emotionally. Misery Bear seems to be asking whether they really do mature in those few years or whether they remain children pretending to be adults, or perhaps only mimicking how they think adults are supposed to act. This leads on to thoughts about how and whether our present Western culture prepares young men in particular for adulthood.

For, beneath the surface humour of Misery Bear, there appears to be a serious and subversive subtext - to what extent this is deliberate or subconscious perhaps only the writers can say. Either way, Misery Bear can also be read as a satirical dramatisation of the plight of young men in the 21st Century West. If we older people are tempted to look down on the younger generation as "snowflakes," shows like Misery Bear perform a valuable role in demonstrating that, for all their casual affluence, life is in many ways much harder for them than it was for us when we were their age.

Those born after the end of the Cold War grew up in the absence of grand narratives. Misery Bear is typical of most of his generation in showing no real religious or political commitment. Like them, he struggles to find meaning or purpose and direction in his life. He is apparently without family, reflecting the lack of family guidance experienced by many, who are also let down by the formal education system. Misery Bear therefore gets his notions of how he is supposed to be living his life from the entertainment media and from advertising. This leads him to joyless attempts at hedonism, exemplified by a night club where stone faced staff bleed him of £20 notes. This seems to be a perceptive commentary on modern life for many, selfishly seeking a happiness they can never find in a selfish quest for selfish pleasure.

Misery Bear is in fact a rare sympathetic portrait of that most despised of demographics, single young men, or "incels" as they are now generally known. Evolution gifts the human race a slight surplus of males over females at birth on the assumption that many will be killed off hunting or fighting. Since few are now killed off like evolution assumed, and abortion has further increased the proportion of males to females globally, the number of single young males is now much greater than the number of single young females. Although some in the media like to present these excess young men as embittered conspiracy theorists, most are more like Misery Bear, lonely and slogging their way through what seems like a pointless existence.

From a dramatic perspective, they make poor protagonists. Young men are simply not loveable. Teddy bears are. So Misery Bear is really about a young man, but he is made more attractive to the viewer by making him a teddy bear, representative of his own recent childhood and his continuing childishness.

If this was the intention, it is a brilliant concept. It is also very well executed. For all the simplicity of the format, an experienced eye can see that it is a production of some sophistication.

It was written and directed by Chris Hayward and Nat Saunders, both of whom wrote for Smack the Pony among other projects. It mimics the style of silent movies, including the blank faced reaction of its star, but it is not entirely silent. On the contrary, the background sound takes on a more prominent role where there is no conversation. Misery Bear himself is permitted a few squeaking noises when he is in a highly emotional state, like a toned down version of Sweep from The Sooty Show, and some of the guest stars in the later episodes are allowed to talk, interacting with the silent Misery, again in a manner reminiscent of The Sooty Show.

Indeed, The Sooty Show seems to have been a major influence on Misery Bear, not least in the way that Misery and the other teddy bears move. If this is a deliberate reference it suggests the possibility that Misery Bear is the naughty little bear grown into a dysfunctional adult, a thought so depressing as to be worthy of Misery himself.

The sense of constant oppressive gloom is enhanced by a great soundtrack. Given the title, it is no surprise that particularly effective use is made of the opening of Simon & Garfunkel's The Sound of Silence and Johnny Cash singing Hurt. One theme hints at turning into the Beatles' Hey Jude, but one more note would probably have cost the BBC a fortune, and, in any case, the song becomes far too optimistic for Misery Bear.

The complete Misery Bear consists of 21 short videos, each 1-5 minutes long, all available on YouTube at the time of writing. The first few episodes introduce us to Misery Bear in his depressing everyday existence - going to work, going to the seaside, going to a night club, going to London, going on a date, etc. Later episodes included quite expensive looking and well observed satires on major feature films, The Terminator, The Night of the Living Dead, and - of course - Misery.

Like any respectable television personality, Misery Bear has done his bit for Comic Relief, Sport Relief, and Children In Need, appearing with Kate Moss, the great Lionel Richie, Mo Farah, Jack Whitehall, Richard Curtis, and Geri Halliwell and Pudsey Bear. The last of these guest appearances was particularly well done, with witty use of suspense.

Like any less respectable television personality, Misery Bear has also written a book, Misery Bear's Guide to Love and Heartbreak, which was well received on Amazon and Goodreads, and which has been translated into French and German. He has over 50,000 followers on Facebook. A "clip show" of his early work was a hit during "lockdown."

So why has he never broken into the mainstream or at least become more of a "cult" star? It does not help that the 1-5 minute format, which is ideal for what it is, makes it inconvenient for commercial broadcast these days. Yet the main reason is that watching a poor little teddy bear getting abused without hope or remission becomes too painful to endure very quickly. It also has to be said there are misjudged moments, including a "behind the scenes" episode which undermines the point of the whole concept by making Misery a spoilt celebrity, and some scenes, like the teddy bear pornography site, one wishes one could unsee. As Miranda went on to prove, the loveable loser trope works only if our protagonist remains agreeable in spite of everything and is given at least a sliver of hope that life will somehow work out. Misery Bear the character is great - not least because the bear cast in the role is strangely expressive - but Misery Bear the show was too relentless. This is a pity because there was a great idea here and even as it is this is a show that deserves to be better known. Looking back, it was perhaps, if anything, a little ahead of its time.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on October 25th, 2023. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.