Missing, Believed Wiped

"By the early 1970's, with no other outlet for many old shows, television companies were finding it harder and harder to justify the expense required to store much of the material they held in their libraries."

Being an old Doctor Who fan I was always conscious of the fact that some 100 episodes or more of the Doctors original adventures were missing from the BBC archives, as a result of a 'wiping' policy that was adopted by the Corporation a few decades ago. However, I soon discovered that it wasn't just the BBC that was solely responsible for destroying a large part of our television heritage, and it certainly wasn't just Doctor Who that had suffered in the process.

Alongside the Corporation (who were only the biggest culprits by virtue of the fact that they held the largest archive), ABC, ATV, Granada, Southern, just about every TV station in the land, helped to create a situation that exists today where literally thousands of hours of "classic" television recordings simply no longer exist, having been systematically disposed of by one method or another. Not only have programmes of both historical and social significance gone missing, but so have entire series of children's programmes, documentaries, and dramas. But to understand exactly how this situation came about, we first need to turn the clock back over seventy years...

In 1947, as an experiment, a 16mm camera was pointed at a television receiver to record the wedding of Princess Elizabeth to Prince Phillip. This was not an impetuous move but a carefully planned and calculated, and in many respects complicated operation. Using a system to match the time it took for the cathode ray beam to reach the screen - to the speed of each film frame as it passed through the camera's shutter gate, a fairly decent quality negative of the broadcast picture was captured on film. And from that negative numerous positive prints could be made. This way a recorded programme could be stored for future generations or distributed to other TV companies around the world.

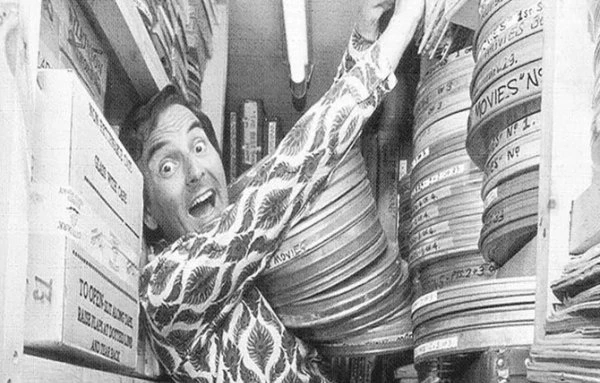

As "tele-recording" became more prolific throughout the 1950's and into the 1960's so archive libraries were required to store the large cans of processed film. These libraries were in fact large warehouses that needed to be fitted with costly air-conditioning systems that kept a constant temperature of 55º Fahrenheit, so that the films would not deteriorate.

Although the storage of these films had their use, there was no obligation by any of the TV companies to retain them beyond their "shelf life". In other words, once the films had been shown on British TV and/or sold abroad, they were of little use to the TV companies other than archival material for television historians. Repeats were frowned upon by the various actors and performing rights' unions as it was considered that taking up airtime with such material would put actors, producers, directors, designers, and the whole body of professionals required to make a TV production, out of work. Eventually settlements were made allowing the broadcast of a certain proportion of repeats a year, but even then this had to be within three years of the original showing. Anything older than that would have to be renegotiated as an entirely new deal.

By the early 1970's, with no other outlet for many old shows, television companies were finding it harder and harder to justify the expense required to store much of the material they held in their libraries. There were other factors to be taken into account, too. Colour television had finally gone on sale in the UK, and the demand for monochrome sets, as well as monochrome TV shows, was dwindling fast. Furthermore, as cans of films were being shipped into the libraries on a daily basis; it was becoming increasingly more difficult to find the space to store them. Warehouses became overcrowded and a fire hazard. As a result, insurers refused to give cover or renew policies. It was at this point that television companies took a decision that would, several years later, impact on the entire history of British television. Any film over the three-year limit and deemed to be of little or no historical value, would be destroyed.

Programmes were categorised or 'graded' by their value in historical terms. Top priority was given to 'A List' shows such as important documentaries or news items or plays by prolific authors such as Dennis Potter or Alan Bleasedale (although these were not entirely preserved). At the other end of the scale were black-and-white shows such as school programmes or the language instructional. But programmes that are today rightly regarded as "classics" were not always 'A Listed', and as a consequence episodes of Steptoe and Son, Hancock's Half Hour, Till Death Us Do Part, Dad's Army, Z-Cars and Doctor Who were purged from the archives over a six year period.

In fact, it was possibly due to a small hardcore faction of Doctor Who fans that the policy finally came to an end. The almost obsessive following that particular series had (and indeed still has) over the years led a group of fans to try and purchase episodes from the BBC when they heard a rumour that certain stories had been marked for deletion. Allegedly, even whilst negotiations were taking place, episodes of the Doctor's adventures were still being junked. These fans were horrified to discover that at that stage over 100 episodes, including entire adventures were missing.

Another factor came into play around that time: Video Cassette Recorders (VCR's) were rapidly growing in popularity and were being made widely available for home purchase at an affordable price, creating a growing demand for pre-recorded material such as feature films and television series. With the dawning of the commercial video age companies suddenly realised the potential goldmine they had almost destroyed, and they hurriedly tried to reverse the process by calling a halt to their junking policy as well as looking at ways of restoring their own lost archives.

Doctor Who fans began a vigorous campaign and were probably the first group of people to begin searching for 'lost' material. And indeed, to some extent they were successful in recovering junked episodes, which in turn alerted archivists to the fact that other 'lost' material may still be traceable. In many cases this involved contacting foreign TV stations that had previously purchased copies of these shows, as they were now the only official source of recovering whatever material they could. In recent years there have been many successes with archive material of all sorts being returned from places as far a-field as Hong Kong, New Zealand, the USA, Nigeria and even from the hands of private collectors.

Before this, private collectors were cautious about admitting to what material they had, worried that they would be sued under copyright laws. This did actually happen to one famous TV entertainer.

For years Bob Monkhouse had been accumulating a large collection of films. These were mainly early black and white comedies of the Keystone Kops variety, but also included many silent and early talkies made by some of Hollywood's greats who were around during that particular golden era. His collection was second-to-none and Monkhouse was considered an expert on the subject of these films. But in the 1970's a major film company decided to sue Monkhouse for infringement of copyright. Monkhouse won his case by proving that although he was in possession of these films, they were purely for private viewing for him or invited guests to his home and in showing them he was not making any financial profit or gain. The decision of the court to find in favour of Monkhouse's defence set a legal precedent by clearing up what had - up to that time – been something of a grey area in copyright law. It also cleared the way for the future of the home video market, which was about to emerge.

Effectively the court’s decision meant that people could hold copyright material in their own homes without the approval of the copyright holders, just as long as holding such material was purely for domestic pleasure and that no financial transaction or profit was made as a result of holding it. This now opened up a new source of recovering lost material for many archivists, and indeed, over the years much material has been returned from the hands of private collectors. In 1993 the British Film Institute launched "Missing, Believed Wiped", an initiative designed to raise the public profile for recovering lost material and Kaleidoscope, a Birmingham based organisation, were set up by a collection of archive enthusiasts, headed by Chris Perry, in order to trace lost media. Returned material is often given to the National Film and Television Archive who have, in the past, made copies of the found material before returning the original to the donor. The Kaleidoscope Archive itself contains over 750,000 items, which include The Bob Monkhouse Collection.

The BFI are always keen to hear from people who believe they may be in possession of British television material and to this end they published a list of the most important missing programmes as well as a book; "Missing Believed Wiped (Searching for the Lost Treasures of British Television)" by Dick Fiddy, who is currently the "Keeper of Television" having succeeded Steve Bryant, himself a former Doctor Who archivist for the BBC.

It is doubtful that many of the lost classics will ever be found, consigned as they are to the TV graveyard for all eternity. However, the search for lost programmes continues and in 2018 the BBC were able to release two previously 'lost' Doctor Who stories after they were discovered in "a dusty room in the African desert" by lost episode hunter Philip Morris. And mainly through the efforts of dedicated fans, professional archivists, and those sometimes 'chance' discoveries, many shows once missing, believed wiped, are now happily preserved for future generations to enjoy...

The Most Important Missing Programmes:

Armchair Theatre: No Tram to Lime Street (ABC 1959)

Written by Alun Owen

A Suitable Case for Treatment (BBC 1962)

Written by David Mercer

Madhouse on Castle Street (BBC 1963)

Director Philip Saville had seen a young man performing in New York and cast him in this drama. He also sang a bit. According to his fans this is the number one missing Bob Dylan item.

Message for Posterity (BBC 1967)

One Dennis Potter play that didn't avoid the clearout.

A for Andromeda (BBC 1961)

Only the last five minutes have survived.

Doctor Who: The Tenth Planet episode 4 (BBC 1966)

The last Hartnell adventure featuring the now famous regeneration scene.

Out of the Unknown series 3 (BBC 1969)

Only one episode survives

The Likely Lads (1964-66)

Although a missing episode was recently rediscovered there are still many absent from the archive.

On the Margin (BBC 1966)

Alan Bennett's musical comedy.

Juke Box Jury (1959-67)

Only two episodes exist from the 1960's but the greatest loss is the show where the panel of judges were comprised of Messer's Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Starr.

Thank Your Lucky Stars (ABC 1961-66)

I'll give it foive but I won't preserve it!

Sunday Night at the London Palladium (ATV 1955-65)

Very few editions have survived.

Opportunity Knocks (ABC 1956-77)

TV Debuts for many top artistes, but sadly hardly any have been preserved.

Moon Landing (July 1969)

The live commentary by Patrick Moore and James Burke in the BBC studio on this historic day is now lost in space.

News at Ten (ITN 3rd July 1967)

The first ever edition.

A Tale of Two Cities (BBC 1965)

Many other Sunday tea-time classics are also missing.

Emergency Ward 10 (ATV 1957-67)

Very few survive. The rest have gone on the sick list.

Jazz Goes to College (1966-67)

The entire series is missing although the most crucial for jazz fans is the loss of the Albert Ayler programme, recorded but never transmitted as it was considered too innovative at that time.

The Crucible (Granada 1959)

Starring Sean Connery and Susannah York. This does actually exist in the archives -minus the last 18 minutes!

Source: BFI

Published on February 2nd, 2021. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.