The Quiz Show Scandals of the 1950s

The scandal involving some of America’s big money television quiz shows was the first major test of the relatively new medium. It forced many Americans to question what was being broadcast on the small screen–and shook the trust of millions of viewers. In a decade where the middle class began enjoying the fruits of their labours with new homes, new cars, the latest gadgets and larger families, the idea of an average Joe or Jane winning big dollars was both admirable and inspirational. After all, America was the superpower of the world, and there was no better way to display the free enterprise system at its best than to reward those with brains. OK, maybe being an expert on sports or cooking were not the best examples. Still, showcasing what “The $64,000 Question’s” creator Louis Cowan called “the common man with uncommon knowledge” became virtually a patriotic duty. And for some contestants and quiz producers, stretching the truth could be justified–if it helped the USA (and themselves), who could complain? As it turned out, plenty–from the President of the United States on down.

EARLY HISTORY: BEFORE THE BIG MONEY

The quiz show was not a new phenomenon. It originated on radio, with simple question and answer programmes, followed by more elaborate games such as “Truth or Consequences.” But the winnings were relatively small, no more than a few hundred dollars or a gift prize from the show’s sponsor. That changed in 1948 when ABC Radio aired “Stop the Music.” An hour-long Sunday night programme, it required listeners to be at home; those who were called had a chance at answering a musical question. It also broke new ground by offering jackpots of prizes–a home, cars, trips and money–to the lucky winner. “Stop The Music” became a outright hit, leading to the demise of Fred Allen’s long-running comedy show on NBC. (Allen had this reaction to “Music” and the big money games that followed: “If I were king for one day, I would make every programme a giveaway show; when the studios were filled with the people who encourage these atrocities, I would lock the door. With all the morons of America trapped, the rest of the population could go about its business.”)

“Stop The Music” was developed by Louis G. Cowan, a documentary producer who seemed to have a golden touch with quizzers. (It was actually created by a man named Howard Connell and his partner, a fledgling game show producer named Mark Goodson; Cowan bought the rights with Goodson as director.) But with television poised for a breakout, the radio quiz was already becoming an endangered species. Indeed, “Stop the Music” would move to ABC’s television network not long after its radio success. Then there was the Federal Communications Commission, which warned the broadcast networks a large-money quiz could be considered a form of illegal gambling. The FCC’s warning forced the networks to limit the prizes and cash that could be won on game shows. In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the FCC’s edict, ruling that quiz shows were NOT a form of gambling. And once again, Louis Cowan was prepared to take advantage of the opportunity.

THE $64,000 QUESTION: HIGH STAKES AND BIG RATINGS

In early 1955, Cowan recalled the old radio quiz “Take It or Leave It,” which offered a top prize of $64. (It was later renamed “The $64 Question,” in part because that’s what people ended up calling it.) Cowan bought the rights to the show and came up with the idea of bringing on everyday people who were experts in one topic or another. Cowan and his staffers found an interested sponsor in cosmetics company Revlon (Chrysler rejected the show, fearing the big money prize would lead to unrest among its unionized factory workers), and CBS agreed to air the new show during the summer.

On June 7th, 1955, the first episode of “The $64,000 Question” aired. It was a revelation in several respects. Instead of a typical game show host, an actor–Hal March–was hired as master of ceremonies, an inspired choice for a show that gave away big prizes. Another innovation was an IBM sorter that seemingly went through hundreds of cards before popping out the questions for the contestant’s chosen category. Each hopeful started off with a question worth $64; the amounts kept doubling until the contestant won $512. At that point, the questions became harder, guarded by a Manufacturer’s Trust Bank employee named Ben Feit, who assured audiences that “except for the producer, no one has seen these questions. Not Mr. March. Not even myself.”

If a contestant reached $4,000 in winnings, things changed: He or she entered an on-stage isolation booth to answer more questions, their difficulty underscored by tense background music. At this point, if a contestant answered wrong, he or she went home with a new Cadillac convertible. But those who won were invited to return to the show the following week, and announce whether to continue toward the grand prize of $64,000.

The isolation booth became the show’s trademark, and viewers loved what they saw. They especially loved the contestants–a Marine with a passion for cooking; a grandmother who knew baseball; and a shoe repair shop owner who adored opera. By the end of the summer, “The $64,000 Question” was an unqualified hit; during the 1955-56 season, “Question” beat all other new and returning shows to end the year as television’s top-rated programme. It also had a positive effect on Revlon sales, as viewers snapped up such products as Living Lipstick and nail polish, resulting in shortages when Revlon plants could not keep up with demand.

Charles Revson, the head of Revlon, would later deny any involvement in manipulating what viewers saw on the big-money quizzer. But those who worked behind the scenes on “The $64,000 Question” recalled otherwise: Revson would strongly imply that certain contestants should be “removed,” and gave his blessing to players he liked. Staffers didn’t give the answers to “Question” contestants, but through pre-show quizzing, found out what they did or did not know in their categories and wrote the questions accordingly. The best-known case involved a young psychologist whom Revson didn’t feel properly represent his products or womanhood overall. That contestant, Joyce Brothers, ended up winning the $64,000 grand prize for her expertise in boxing and went on to a very successful career as a writer and television celebrity, described by one observer as “a sort of cross between Ann Landers and Sigmund Freud.” By this time, Louis G. Cowan left production altogether for CBS, where he eventually became head of the television network; the remaining staffers renamed the company EPI (Entertainment Productions Incorporated).

Staffers quickly developed a second big-money show, which was launched on NBC in the fall of 1955. “The Big Surprise”–hosted by future “60 Minutes” correspondent Mike Wallace–offered $100,000 to the grand prize winner. But viewers never warmed to the complicated show, and it was eventually cancelled. Undaunted, EPI sold CBS on a spin-off of “The $64,000 Question.” The new show, “The $64,000 Challenge,” allowed former “Question” winners to match their skills against celebrities and other contestants for a chance to win more cash. After the first host, Sonny Fox, showed a tendency to make major bloopers on the live programme, he was replaced with Los Angeles-based personality Ralph Story, who was a better on-air host and helped turned the show around. By the summer of 1956, “Question” and “Challenge” were the two most-popular programmes on television. NBC, by now running second to CBS in the ratings, could not let the game show genre go unchallenged. It began offering such shows as “Queen For A Day” and “The Price Is Right” in daytime to challenge CBS’ popular soap opera line-up, and turned to a pair of game show veterans for a series that would give “The $64,000 Question” a run for its money.

TWENTY ONE: BIGGER MONEY AND MORE MANIPULATION

Jack Barry and his partner Dan Enright were no strangers to broadcasting. The two men developed such hits as “Juvenile Jury” and “Winky Dink and You.” Barry was the on-screen host; Enright was the man behind the curtain. That formula continued in their latest venture, “Twenty-One,” which premiered September 12th, 1956. Based on the casino card game, two contestants (each in soundproof booths) answered questions worth between one and eleven points; the higher the number, the harder the question. The goal was to get to 21 first. Neither contestant knew the score of the other, and either contestant could stop the game at any time.

Even better, there was no limit on how much a player could win and the victorious contestant could go on week after week, as long as he or she continued to win. “Twenty-One” was sponsored by the tonic Geritol (for those with “Iron Poor Blood”). The first match was on the up-and-up, but it ended in a tie and lacked any drama or entertainment value. Enright later said the head of Pharmaceuticals, Incorporated (Geritol’s maker at that time) threatened to end his company’s sponsorship if he saw another lacklustre episode. As a result, the fix was in: Enright and the show’s staff treated “Twenty-One” like a scripted series. Each contestant was carefully chosen and desirable contestants were given the answers to the questions that would be asked on the air. Further, the contestants were told which questions to answer and which ones to miss; they were also instructed how to dress, the proper way to react on the air, and even when to mop their brows for dramatic effect (the air conditioning in their isolation booths were cut off during questioning so they would sweat more). But “Twenty-One” made little headway in the ratings, and to make matters worse, NBC moved the show to perhaps its toughest time slot–Monday nights at 9:00 PM, against CBS’ formidable “I Love Lucy.”

The show finally received its own shot of Geritol when a young, handsome college professor named Charles Van Doren appeared for the first time as a contestant on November 28th. He faced the reigning champion, Herbert Stempel, a 29-year-old former soldier who was becoming unpopular with both staffers and the sponsor. The two men squared off in a series of tie games, until December 5th, when Enright ordered Stempel to “take a dive.” Ironically, the question that would seal Stempel’s fate was one he really knew the answer to: “Which motion picture won the Academy Award for 1955?” The correct answer was “Marty,” which happened to be Stempel’s favourite film. But he was told to answer with “On the Waterfront.” Fearing he would become an obscurity and would not be considered for other Enright-Barry shows if he didn’t follow instructions, Stempel gave the wrong answer on the air. That move allowed Van Doren to “beat” Stempel. After the live show, a defeated Stempel became angry when a staffer praised the clean-cut Van Doren and called Stempel a “freak with a sponge memory.”

Even more galling for Stempel, his former opponent was becoming a new American hero, as he defeated one opponent after another, week after week. By early 1957, Charles Van Doren not only made the cover of “Time” magazine, he became a shining example to parents who feared juvenile delinquency and the gyrations and groans of teen singing idol Elvis Presley. Van Doren’s popularity also helped “Twenty One,” as the show began closing the ratings gap with “I Love Lucy” in head-to-head competition. In late February, Van Doren was locked in a dramatic battle of brains with attorney Vivienne Nearing (billed by NBC as “the lady lawyer”). “Twenty-One” became the first regularly-scheduled series to beat “Lucy” in the ratings. Their final match was set for March 4th, but it was delayed one week–amid outcry–when NBC aired a version of “Romeo and Juliet” that night as part of its regularly scheduled Monday night “spectaculars.” On March 11th, Van Doren lost to Nearing, but walked away with both a total of $129,000 and a contract to become a regular contributor on NBC’s “Today” show. Soon after, NBC bought out Barry and Enright’s ownership of “Twenty-One.”

Meanwhile, ratings for the two EPI shows began slipping. Producers modified the rules, allowing contestants on “The $64,000 Question” to win even more money before having a chance to add to their winnings on “$64,000 Challenge.” By this time, a number of big money quiz programmes were airing on the three major networks, each one seemed to offer more cash and prizes than the other. In response to the growing jackpots on other shows, Groucho Marx announced any contestant who said the “secret word” on his popular game show “You Bet Your Live” would win $101 instead of the old amount of $100! Rumblings began about some quiz shows being “controlled” or not totally honest; the allegations initially didn’t stick. But soon, the dirty little secret of the big-money shows would become public knowledge.

THE FINAL QUESTION AND VAN DOREN’S MEA CULPA

Charles Van Doren’s post-“Twenty-One” success continued to irritate Herbert Stempel, a situation that was not helped by Dan Enright’s reluctance to find Stempel a job in television. It wasn’t long before Stempel went public with his claim he was told to lose to Van Doren. But he had no hard evidence; Enright claimed Stempel was “mentally disturbed;” and newspapers feared libel suits if they published Stempel’s story.

But all that was about to change.

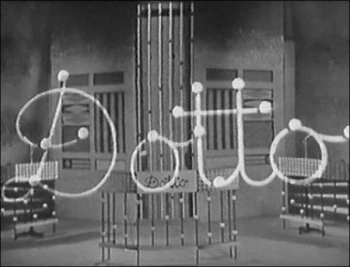

In 1958, the CBS game show “Dotto” (which involved connecting the dots to identify a famous figure) became the top-rated programme on daytime television. One May day, a standby contestant named Ed Hilgemeyer was watching the live programme backstage and noticed the current “Dotto” champion, Marie Winn, giving the correct answers a little too smoothly. Hilgemeyer discovered Winn was reading a notebook during commercial breaks. He quickly looked into the book–and found the same answers Winn was giving on air! Hilgemeyer told the losing contestant about the notebook and together they confronted “Dotto’s” producers, who came up with a cash settlement. But Hilgemeyer was given a small amount of money to keep silent, and quickly contacted the network, the sponsor (Colgate-Palmolive) and the New York City District Attorney’s office. CBS, NBC (which aired a prime time version of “Dotto”) and Colgate reviewed a kinescope of the show featuring Winn. “Dotto” was immediately cancelled, replaced on CBS with the ironically-named “The Big Payoff.” (The show’s host, Jack Narz, didn’t know about the behind-the-scenes shenanigans and offered to take a lie detector test, which he passed. He became host of “Big Payoff.”)

The “Dotto” scandal also led to the publication of Stempel’s charges about “Twenty-One.” New York district attorney Frank Hogan convened a grand jury, which heard testimony from dozens of witnesses–most of whom committed perjury by lying about the deceptions of various quiz shows and staffers. One contestant did tell the truth. James Snodgrass, who won about four-thousand dollars on “Twenty-One,” told the grand jury he was given answers in advance, then was told to lose. And Snodgrass had proof: He unveiled several sealed registered letters he had mailed to himself before one of his “Twenty-One” appearances; the letters contained the questions and answers that were asked and answered on the show, along with instructions on how to behave on air.

It was the final straw for the once high-flying big money quiz shows. “The $64,000 Question,” “The $64,000 Challenge” and “Twenty-One” were cancelled by the fall of 1958 and several people were indicted for perjury. But there was no law on the books making it illegal to rig a quiz show, and many people expected the scandal to die.

It would have, except for the fact that a New York federal judge named Mitchell Schweizer ordered the grand jury testimony to be sealed. The reason was never given, but the grand jury’s foreman spoke out, saying the public “should have access to these facts.” And what the city of New York could not do, the United States Congress did. Utah Congressman Oren Harris, who chaired the House Legislative Oversight Committee, began probing the big money quiz shows and called witnesses to Washington, DC. Charles Van Doren–by now a success as a regular on “Today” and newly married–had maintained his innocence. No, he said, “Twenty-One” was not rigged and he wasn’t given the questions or answers in advance. But as more and more people began telling the truth to Congress, Van Doren–facing a subpoena to appear before Harris’ committee–suddenly disappeared. He re-emerged to testify on November 2nd, 1959 and confirmed what others had claimed: The fix was in on “Twenty-One.”

"I was involved, deeply involved, in a deception. The fact that I too was very much deceived cannot keep me from being the principal victim of that deception, because I was its principal symbol."

Americans also learned about the manipulation of other contestants and were shocked when it was revealed child star Patty Duke was coached before her appearance on “$64,000 Challenge;” she survived the episode to become an award-winning actress. And the sordid details of manipulation and coaching were laid bare for everyone to digest.

THE AFTERMATH

Charles Van Doren, who finally told the truth, probably fell the furthest from grace; he lost his NBC job and was fired as a college professor at Columbia University. He soon went into hiding, and for years was an editor for the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Van Doren didn’t tell his story until 2008, when he wrote about his quiz show experience for “The New Yorker” magazine. Here’s a link to the Van Doren article:

http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2008/07/28/080728fa_fact_vandoren

Dan Enright and his less implicated partner Jack Barry were essentially drummed out of American broadcasting for a time. Enright eventually went to Canada to develop game shows while Barry won a license to run a California radio station. The two men resumed their partnership in the early 1970's, and came up with a string of hit game shows–“The Joker’s Wild” and “Tic Tac Dough” to name two of them–restoring their reputations. And yes, the new Barry-Enright entries were scandal-free.

Louis G. Cowan was hospitalized during the height of the scandal, but was forced to resign as president of the CBS Television Network in late 1959. Executives claimed Cowan’s performance at CBS was the reason; others contended Cowan had become a scapegoat when the quiz scandals broke. In any case, he was replaced by another controversial figure–James Aubrey. Louis Cowan and his wife Polly died in 1976, after a fire swept their penthouse apartment on New York’s Park Avenue.

Executives of the three major television networks were called to testify before the House Legislative Oversight Committee. ABC executives claimed (correctly) they had few if any big money quiz shows on the air and took no responsibility for the scandal. NBC executives denied knowing what was going on behind the scenes of “Twenty-One” and the network’s other quiz shows. Only CBS President Frank Stanton took responsibility; his testimony was credited with heading off efforts by Congress to further regulate the three networks. Instead, a law was passed, making it illegal to rig a quiz show.

Reaction was swift but varied. President Dwight Eisenhower commented on the scandal, calling it “a terrible thing to do to the American people.” Meanwhile, “Consumer Reports” ran an article entitled “Where, May We Ask, Was The (Federal Communications Commission)?” It was an appropriate question: As the quiz show scandal went into high gear and Congress began investigating alleged “payola” in the radio and record industries, it was learned FCC Chairman John Doerfer was accepting free trips from a major radio station owner. Doerfer stepped down under pressure in early 1960. Perhaps the funniest response came from Bob Hope, who joked, “Successful contestants are being brought back for one more question: How do you plead?” Talk show host and acclaimed television producer David Susskind was more pious, claiming the quizzers were “monuments of mediocrity, stupidity and dullness. I’d like to see them driven off the air.” Susskind went on to produce a 1965 ABC game show called “Supermarket Sweep,” where contestants raced to see who could fill their carts with the most expensive merchandise; it was considered one of the worst game shows in American television history.

Because there was no law making it illegal to fix a quiz show at the time, more than 20 people involved were charged with perjury (lying before a grand jury). All received suspended sentences. “Variety” correctly summed up the aftermath, noting the quiz scandal “injured broadcasting more than anything ever before in the public eye.”

The major networks stayed away from big money game shows after the scandal and put tight restrictions and prize limits on those still on the air. In 1963, ABC tried again with “100 Grand,” a prime time quizzer that proved to be rather boring and long-winded; it left the airwaves after just three episodes. Big money quizzes finally made a comeback on American television in 1999, when ABC aired the U.S. version of the British hit “Who Wants To Be A Millionaire.” Its success led the other networks to launch their own big money shows. NBC even dusted off the old “Twenty-One” format for an above-board (but short-lived) revival.

In 1994, the Robert Redford-directed film “Quiz Show,” was released. Billed as a morality play, it was loosely based on the scandal and the events that occurred on “Twenty-One.” It featured fine performances by Ralph Fiennes (as Charles Van Doren), Paul Scofield, Rob Morrow and John Turturro, who played Herb Stempel. Critics generally liked “Quiz Show,” even though the time line of events was changed for dramatic purposes. Although “Quiz Show” was not a box office smash, it won four Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture and Best Director for Redford.

Published on December 6th, 2021. Written by Michael Spadoni (2010) for Television Heaven.