Carry On Camping

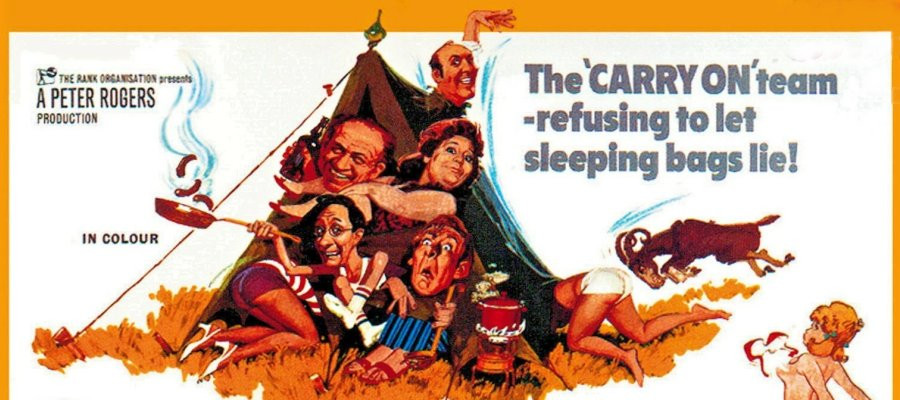

If ever a film encapsulated the cheeky, wonky charm of British comedy in its prime, it’s Carry On Camping. Released in 1969, the seventeenth entry in the long-running series quickly cemented itself as a fan favourite, and half a century on it remains one of the most warmly remembered of the lot. It had all the essential ingredients: an irrepressible ensemble cast, a delightfully silly premise, and the sort of good-natured naughtiness that made the Carry Ons both scandalous and strangely wholesome at the same time.

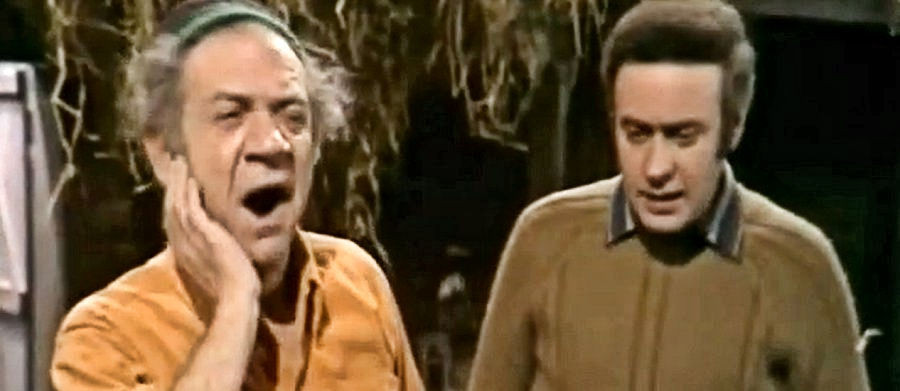

At first glance, the set-up seems almost sensibly straightforward. Sid Boggle, played with trademark twinkly-eyed mischief by Sid James, is a plumber with ideas far above his station. Alongside his lanky business partner Bernie Lugg (Bernard Bresslaw), he concocts a daring plan to whisk their girlfriends—prudish Joan Fussey (Joan Sims) and timid Anthea Meeks (Dilys Laye)—off for what he hopes will be an eye-opening holiday. A trip to the cinema exposes Sid to a “naturist” film set in a place called Paradise, and he decides that visiting this particular resort might be just the thing to soften the girls’ unyielding sense of propriety. Like so many Carry On schemes, it is both optimistic and woefully misjudged.

On arrival, Sid and Bernie discover—far too late—that Paradise has been somewhat misrepresented. Rather than the carefree nudist haven of the film, they find a boggy field presided over by Peter Butterworth’s shamelessly penny-pinching farmer, Josh Fiddler. Facilities extend to a toilet block so primitive even the most hardened outdoorsman would hesitate, and a general atmosphere of damp discomfort hangs over every scene. The irony, naturally, is that this campsite still appeals to Joan and Anthea, who are charmed by its rustic simplicity. And so the men must soldier on, hopes of a saucy getaway sinking almost as quickly as their wellies.

The production’s real-life conditions did nothing to improve matters. Filmed not in some idyllic summer stretch but in the wet chill of November, the cast spent much of their time battling mud that threatened to swallow them whole. Leaves had long since fallen, so the crew resorted to spray-painting foliage and daubing greenery onto the bog to maintain the illusion of sunnier times. One might imagine such discomfort dampening spirits, yet the adversity only seems to add to the film’s ramshackle charm. Watching characters repeatedly skid, sink and slide about the set becomes a layer of comedy all of its own—though the cast may not have appreciated the joke at the time.

As in most Carry Ons, the campsite is soon invaded by a lively cross-section of oddballs. Charles Hawtrey turns up as Charlie Muggins, a hopelessly naïve first-time camper whose idea of outdoor adventure feels lifted from a Boy Scout manual circa 1910. Terry Scott appears as Peter Potter, dragged reluctantly into nature by his overbearing wife Harriet (Betty Marsden). Marsden, with her ludicrously braying laugh and unstoppable bustle, steals practically every scene she’s in. She embodies the sort of relentless holiday-maker who believes misery is best shared loudly.

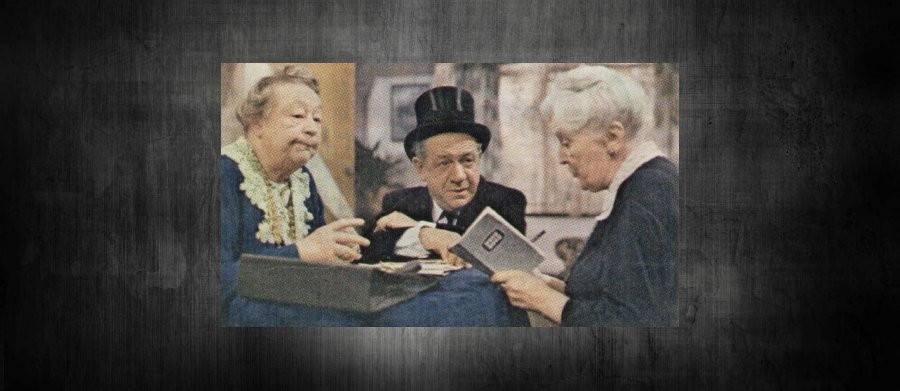

Yet the film’s most memorable arrivals are the girls from the Chayste Place finishing school. Led by the irrepressible Babs, played by Barbara Windsor with her trademark bubbly energy, they spark immediate interest from Sid and Bernie. Kenneth Williams, as the pompously moralistic Dr Soaper, attempts to keep the girls in line, while Hattie Jacques’ lovelorn Miss Haggard pursues him with equal determination. Their interplay is a delight—Williams’ strangulated indignation paired with Jacques’ dogged yearning produces some of the film’s most deliciously absurd moments. There’s even a sly little in-joke referencing Jacques’ turn in Carry On Doctor, when her character casually alludes to her past in hospital work.

The finishing-school girls soon move on to a youth hostel, giving rise to one of the film’s most famous pranks. Babs and her friend Fanny (Sandra Caron) swap door numbers and trick Dr Soaper into blundering into the wrong washroom, where Miss Haggard is enjoying a peaceful moment. The farce that unfolds is pure Carry On: the perfect blend of risqué and ridiculous, built around misunderstandings, misplaced dignity, and Williams’ peerless ability to look both wounded and outraged in the same breath.

Of course, no discussion of Carry On Camping can avoid that scene—the one that entered British comedy legend. During one of Dr Soaper’s outdoor exercise classes, Babs’ bikini top unexpectedly flies off, leaving her hopping about in scandalised shock while he ends up catching the errant garment. The moment defined Barbara Windsor’s association with the Carry Ons forever, though it nearly went in a very different direction. She had initially intended to play Babs with a refined public-school accent, only to lapse into her natural Cockney tones during the early shower-scene shoot. Director Gerald Thomas, seizing the spontaneity, allowed the slip to stand—and Babs’ uniquely East London sparkle shone through the rest of the film.

As if the camp weren’t chaotic enough, a horde of hippies eventually descends upon the neighbouring field, complete with The Flowerbuds providing a continuous soundtrack of strumming and chanting. Their all-night revelry pushes the long-suffering campers to breaking point. Everyone bands together to oust the intruders, only for the schoolgirls to flounce off with the hippies in triumph. Nevertheless, romance waits in the wings: Joan and Anthea finally agree to share a tent with Sid and Bernie, only for Joan’s formidable mother to arrive at precisely the wrong moment. Salvation comes in the unlikely form of a goat unleashed by Anthea. It’s a victory of sorts—chaotic, sudden, surreal, and entirely consonant with the Carry On spirit.

Much of the film’s magic stems from the ensemble cast’s chemistry. These actors had worked together across numerous entries, and their familiarity bred sharp timing rather than complacency. Sid James’ roguish warmth plays perfectly against Joan Sims’ flustered propriety. Kenneth Williams’ razor-sharp delivery dovetails with Hattie Jacques’ imperturbable deadpan. Bresslaw’s looming physicality contrasts with Hawtrey’s spindly gormlessness. Even the smallest exchanges feel effortlessly alive, as if the performers were simply delighted to be back in each other’s orbit. The jokes land not merely because of the writing, but because the actors understand exactly how to tease every ounce of humour from a glance, a splutter, or a raised eyebrow.

What also stands out is the film’s gentle balancing act between slapstick mayhem and sly verbal wit. Yes, people tumble into mud pits and flee from rampant livestock, but they also fire off beautifully timed one-liners and outrageous puns. It’s far broader comedy than one finds today, but there’s a kind of innocence to it—a belief that laughter, wherever it comes from, is worth celebrating.

Despite being set in the height of summer—and looking anything but—the film was a runaway success. At its premiere in Hull, audiences queued round the block, eager for a dose of sunny escapism during a particularly grey British winter. It went on to become the highest-grossing UK film of 1969, with its predecessor Carry On Up the Khyber snapping at its heels. Not bad for a modestly budgeted comedy made in knee-deep sludge.

Time has only strengthened its reputation. In 2008, readers of the Daily Mirror voted Carry On Camping the nation’s favourite entry in the series, and a decade later the British Film Institute named it one of the five best Carry On films ever made. These accolades aren’t merely nostalgic indulgence; they speak to the film’s enduring ability to make people laugh, to transport them to a sillier, more harmless world where trousers fall down, tempers flare, and love triumphs in the most unlikely fashion.

Looking back, one can’t help but chuckle at the casting curiosities. Sid James, at fifty-five, and Joan Sims, at thirty-eight, hardly resemble a young couple still negotiating the earliest stages of romance. Barbara Windsor, playing a mischievous schoolgirl at the age of thirty-one, is equally improbable. Yet such implausibilities are part of the Carry On charm—age, dignity, plausibility: none of these ever stood in the way of a good gag.

Carry On Camping is, ultimately, a film stitched together from warmth. Its jokes may be broad, its scenarios daft, and its setting muddier than a Glastonbury car park, but its heart beats steadily beneath the farce. It captures a moment in British cinema when comedy could be rude without cruelty, brash without bitterness, and playful without pretence. Watching it now feels like joining old friends on a holiday that’s gone terribly wrong but is somehow, gloriously, all the better for it.

It’s no wonder audiences still pack their metaphorical rucksacks and return to Paradise time and time again. For sheer, joyous, soggy silliness, Carry On Camping remains unbeatable.

Published on December 1st, 2025. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.