From Out of Town to Countryfile

A Look at Rural Life on Television

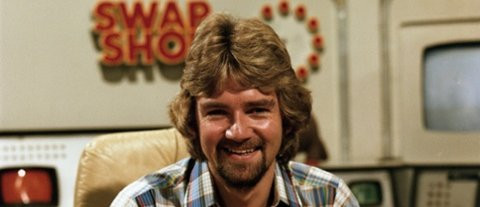

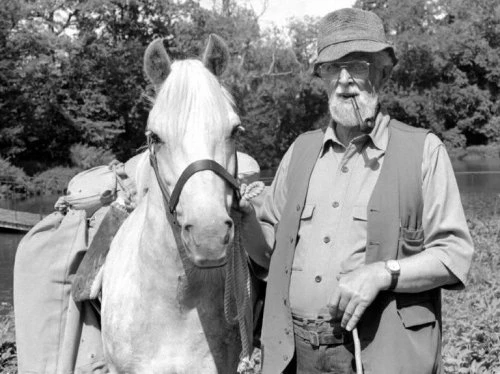

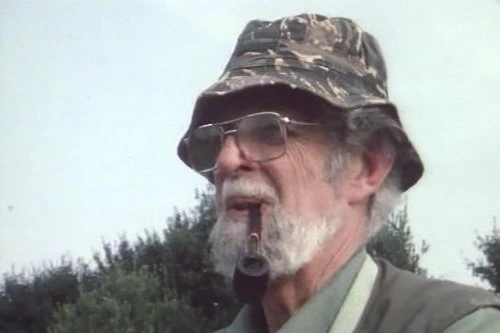

When Out of Town first appeared on British television in 1963, it offered viewers something quietly radical. Jack Hargreaves, seated in his shed-like studio, would introduce short films of rural crafts, fishing trips, farming practices, and countryside traditions. His commentary was reflective and conversational, often tinged with nostalgia but never sentimental. Hargreaves sought to explain the countryside to an increasingly urban audience, not as a romantic idyll but as a working landscape shaped by skills, customs, and rhythms that were already beginning to fade. The series, which ran until 1981, became a kind of living archive, preserving on film the crafts of blacksmiths, hedgelayers, and shepherds at a time when mechanisation and modernisation were transforming rural life.

By contrast, when the BBC launched Countryfile in 1988, the tone and ambition were very different. Where Out of Town was intimate and personal, Countryfile was broad, polished, and journalistic. Instead of a single voice guiding the viewer, a team of presenters covered farming, environmental issues, rural politics, and human-interest stories. The programme was designed for a national audience, not just those with ties to the countryside, and its Sunday evening slot quickly made it a family ritual. It was less about preserving memory than about engaging with the present: food production, conservation, rural policy, and the challenges of modern farming. If Hargreaves’ shed was a place of quiet reflection, Countryfile was an outdoor window onto the living countryside, framed by sweeping camera shots and professional reportage.

The evolution from Out of Town to Countryfile mirrors broader changes in factual television. In the 1970s and 1980s, experimental series such as Living in the Past placed volunteers in reconstructed Iron Age settlements, foreshadowing the immersive reality genre. Later, productions like The Victorian Kitchen Garden and The Victorian Kitchen recreated historical working practices, blending education with gentle reality drama. By the 1990s and 2000s, this impulse had developed into full-fledged “time-travel” reality shows such as The 1900 House and The 1940s House, which asked modern families to live under historical conditions. These programmes combined social experiment with documentary, showing how ordinary people coped with the hardships of past rural life.

In the twenty-first century, rural reality television diversified further. The Great British Bake Off reframed traditional skills in a marquee pitched in the English countryside, turning baking into a global phenomenon. Ben Fogle: New Lives in the Wild explored individuals who had abandoned urban life for remote, rural living, while Clarkson's Farm brought celebrity-led reality to agriculture, mixing humour, hardship, and genuine insight into farming. These shows reflect a cultural shift: the countryside is no longer just a backdrop for nostalgia but a stage for experimentation, aspiration, and even satire.

Comparing Out of Town and Countryfile highlights the distance television has travelled. Hargreaves’ programme was a solitary meditation, a man in a shed recalling and recording traditions that were slipping away. Countryfile, by contrast, is a collective endeavour, a national platform for rural issues, polished and professional but less personal. Both, however, share a common purpose: to connect audiences with the countryside, whether through memory, reportage, or debate.

From Hargreaves’ quiet monologues to the drone-shot panoramas of Countryfile, and from immersive historical experiments to celebrity farming ventures, the fascination remains constant. The countryside continues to exert a powerful pull on the national imagination. What has changed is the way television frames it—sometimes as a record of the past, sometimes as a site of political struggle, and increasingly as a stage for entertainment. The journey from Out of Town to Countryfile and beyond is not just the story of rural programming, but of television itself: evolving from reflection to reportage, from documentary to reality, while never losing sight of the enduring appeal of life lived closer to the land.

Published on October 10th, 2025. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.