Out of the Unknown: The Dead Past

Isaac Asimov, one of science fiction's most celebrated authors, had no fewer than six stories adapted for Out of the Unknown. For a series that focused on intelligent science fiction, that showcased big ideas rather than flashy action, Asimov was a perfect match. Of the Asimov episodes, only two remain in the archives: “The Dead Past” and “Sucker Bait,” both from the first season. The remaining four have sadly not survived the BBC's binning, although a reconstruction of season three's “The Naked Sun” is available on the comprehensive DVD boxed set.

Of Asimov's many works of science fiction, “The Dead Past” was a perfect choice to adapt for the series. The short story, originally published in 1956, combines an ingenious central conceit with strong character work – not always Asimov's strongest suit – to excellent effect. What's more, being a very self-contained tale, it was possible to film it with a small cast on a handful of sets. Indeed, it would be perfectly suited to a low-budget stage play.

Asimov's story, here adapted by Jeremy Paul and directed by John Gorrie, is set in a dystopian future, but a rather more one subtle than most. Unlike much sci-fi, which features scientists that are jacks-of-all-trades, Asimov's story recognises that most academics are specialists. In this future, however, specialisation has become so entrenched that scholars are forbidden by law to even enquire outside their field. A huge bureaucracy oversees this state, keeping knowledge compartmentalised. It's this central government that keeps the most amazing technology of the age – the Chronoscope – under wraps.

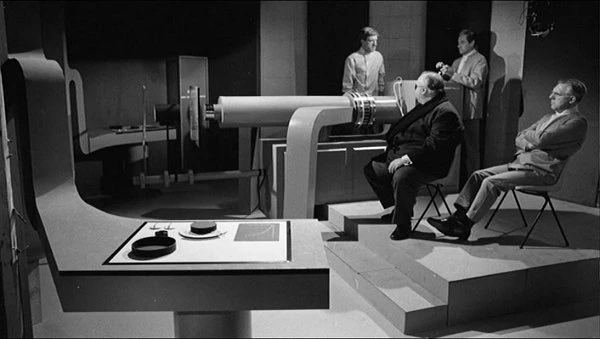

The Chronoscope is a device that allows the operator to replay events from the past, anywhere and anywhen, as if they were recorded on video. It utilises the fictional science of neutrinics: imaging of neutrinos. Utterly preposterous, of course; neutrinos are virtually undetectable and would be a terrible choice of medium in the real world. In this future, however, the Chronoscope is very much real, and all operation is kept under control by the government.

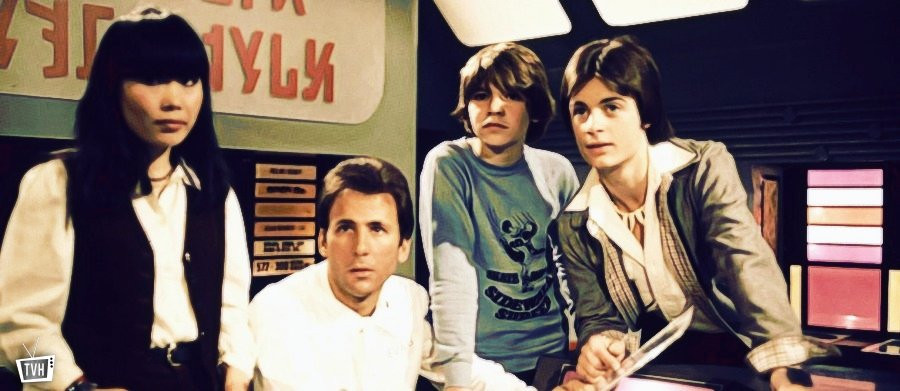

Our protagonist, the mild-mannered Arnold Potterley (George Benson), petitions for use of the Chronoscope. A professor of ancient history specialising in Carthage, Potterley wants to use the technology to prove his theories on Carthaginian culture; specifically, whether the Carthaginians really sacrificed their children by fire, or whether it was, as he believes, propaganda put about their enemies. Potterley is immediately denied access to the 'scope, and seeks out the young physicist Jonas Foster (James Maxwell) to build him a working Chronoscope from scratch.

What transpires is a story of obsession, one that builds to a remarkable revelation. Both Benson and Maxwell are excellent as men driven by their obsession to build the Chronoscope, yet always at odds. Initially, Foster is repelled by the idea, not least because it would involve both him and Potterley transgressing the law that keeps them in their specific fields. Yet, as he is tempted to work on the project, it is Foster who becomes driven to build the Chronoscope at any cost, while Potterley turns on his heel and begs him to stop.

The truth behind the matter comes out in fits and starts. Foster deduces that, in spite of the government's claims, it is impossible to use the Chronoscope to look back as far as the First Millennium BC, because signal noise builds up so much it drowns out everything. The furthest back anyone could see would be about 120 years earlier. The concept of free access to the recent past horrifies Potterley, for both philosophical and personal reasons. For his obsession with child sacrifice by fire stems from his guilt at the death of his daughter in a house fire, which, he reveals in a heartbreaking scene, may have been his fault due to a discarded cigarette butt.

Who could resist the temptation to use the 'scope to watch their lost loved ones? Certainly not his wife, Caroline (Sylvia Coleridge), still torn apart by grief. Coleridge's performance is the strongest in the episode, her character slowly falling apart as she faces the devastation of her loss again. From her perspective, her husband is trying to stop her seeing her daughter. From his, he is saving her from becoming lost in the dead past, unable to ever move forward.

There is, of course, more to it. Foster conspires with his influential and rebellious uncle, the journalist Ralph Nimmo. Played by the expansive Willoughby Goddard, in cloak, eyepatch and wheelchair, the fruity and eccentric Nimmo provides some much needed comic relief to keep things from getting too oppressive. He and Foster, spurred on by greed and intellectual pride, determine to make the Chronoscope available for all.

Cue one Thaddeus Araman (Asimov had a way with character names), played sympathetically by David Langton. Araman, representing the supposedly bureaucratic and repressive government, swoops in to arrest Potterley and the conspirators. In a pleasing twist, Araman reveals that the government's suppression of the Chronoscope technology is not mere authoritarianism, but a necessity. For while there is a maximum limit to neutrinics, there is no minimum; the Chronoscope can look back a century, a year, a day, or the last brief half-second. Araman's agency has been watching the conspirators all the time, for the dead past is simply “the living present.” What would happen if such technology, capable of spying, voyeurism and blackmail, made its way into the public's hands? Unfortunately for the future, there is one further twist to come. The episode ends with a simple, yet haunting sequence of images, of the Potterley's lost daughter, playing again and again in silence. The past is no longer dead, and as for the present...

A potentially dry story enlivened by an impressive and affecting cast, the first Asimov adaptation proves to be one of Out of the Unknown's strongest episodes. If you like your sci-fi with action and impressive effects, this isn't for you. If, however, you like sci-fi that makes you think and sticks with you long after you've finished watching it, “The Dead Past” is dead good.

About the Writer of this article, Daniel Tessier

Dan describes himself as a geek. Skinny white guy. Older than he looks. Younger than he feels. Reads, watches, plays and writes. Has been compared to the third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, tenth, eleventh and twelfth Doctors, and the Dream Lord. Plus Dr. Smith from 'Lost in Space.' He has also had a short story published in Master Pieces: Misadventures in Space and Time a charity anthology about the renegade Time Lord.

Dan's web page can be here: Immaterial

Published on December 16th, 2019. Written by Daniel Tessier for Television Heaven.