Jacqueline Mackenzie

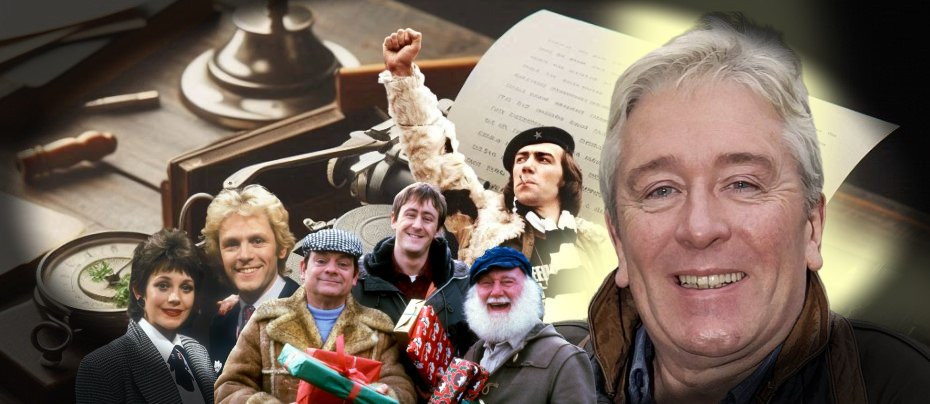

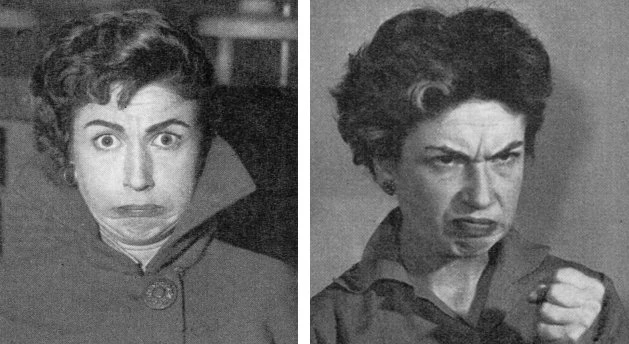

Many people today will be unfamiliar with the name Jacqueline Mackenzie. The British born writer and TV presenter had a brief career in the 1950s as an actress before embarking on a new one as a news reporter, quickly becoming a favourite of producers and the public with her sharp, lively, and quirky delivery on programmes like Highlight, Newsnight and Late Night Extra. Her coverage of the wedding of Prince Rainier to Princess Grace in 1956 won her the Prix d ’Italia. Mackenzie was sharp, a gifted mimic with a lively comical acidity and a face that could suddenly take on bizarre mannerisms. She forged a completely fresh form of reportage, live to camera, that made television history. But her life changed whilst on a visit to America, in 1957, where she had her first lesbian affair. In the 1960s, Mackenzie, as Jackie Forster, became a trailblazing gay rights activist speaking openly about her identity and helping viewers find the strength to accept themselves. Jackie’s courage in coming out during less enlightened times made her a role model to thousands.

Jacqueline Moir Mackenzie was born on 6 November 1926 in London, to Scottish parents. Her father served as a colonel in the Royal Army Medical Corps, stationed in British India, and as a result, Jackie spent most of her early years there. At the age of six, Jackie’s parents decided to send her to a boarding school in the United Kingdom. She attended Wycombe Abbey and then moved on to St. Leonards School in Fife. Good at sports, she played lacrosse and hockey for Scotland during the Second World War. After the end of the War, Jackie made her foray into acting and joined Edinburgh’s Wilson Barrett repertory company before moving to London in 1950 and attending the Arts Theatre Club.

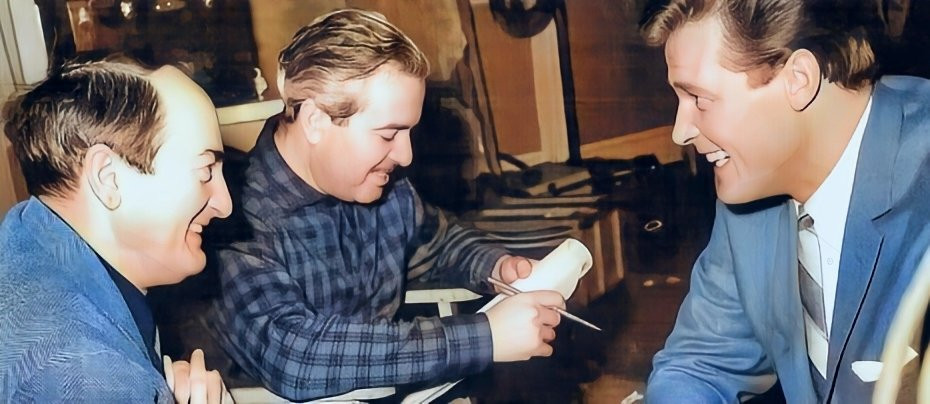

Jackie landed her first role in television in a 1951 (shown under the umbrella title of the BBC’s Sunday Night Theatre) adaptation of W. Somerset Maughan’s Caesar’s Wife. She continued to try and forge her career in drama with appearances in a number of Sunday Night Theatres over the next couple of years, but without ever being a leading light. The closest she came was in the 1955 adaptation of John Drinkwater’s 1928 comedy Bird in Hand in which she starred alongside Terry-Thomas. But by that time her career was destined to take a different path.

In 1957 she wrote an article, full of wit and wisdom, (published in The Television Annual 1958) titled How to Stay in Television, which one can assume was semi-autobiographical.

‘For the uninitiated, the entrée into television is to write a letter requesting an interview. Duly you receive an answer stating a date and a place, and you go. You are interviewed in an office inhabited by filing cabinets, harrowed secretaries and inexhaustible telephones. You are told that an audition will be held sometime in the future – you will hear when.

During the intervening weeks, you rush round to your friends for advice. They tell you that you must act natural on the screen, stay relaxed and never make faces. If you intend to act, a variety of short sketches are recommended – dramatic, comedy, dialect. If you are an act, a variety of gimmicks are recommended. If you are a personality no audition is recommended.

Eventually the audition arrives. In my day I did it in a sound studio with no cameras. Mysterious disembodied voices told me to start, listened, told me to stop, and said “Thank you.” I eventually located a lot of women behind glass, sitting with hands over their eyes. As a result of my histrionic solo (I intended to act), I was offered the part, in a play, of a silent dancer at a ball. Then a spate of stage-management jobs, which kept me firmly away from the cameras.

For the initiated, the entrée into television is to have a huge capacity for beer and linger in the TV pubs. If the money lasts out, you might be offered a half-minute in a women’s afternoon programme, or contribute a noise in a commercial.

Having achieved a brief moment on the screen your ego is so inflated that you assume that you have “arrived.” At this stage it is advisable to buy the Radio Times and the TV Times. From these you note producers’ names and write to them, telling the date and hour of the programme in which you took part. If they reply, they will tell you they didn’t see you: immediate deflation of ego. This takes some months, after which you humbly apply for the most menial studio task. This entails pursuing a completely new breed of television personnel, who live at inaccessible places; and if you are not a member of a union they won’t even open your letter.

Balked at every turn, you resort to your own pastimes, hobbies or job and get on with it. For instance, you are a Sagger Maker’s Bottom Knocker. The Variety Department hear of you through one of the studio chauffeurs, who is a chum of yours. Variety Bookings ring you up and you appear on a quiz programme. You are a riot because you are rude to a personality “in vision,” i.e. in front of the cameras.

The Talks Department are watching, and offer you an interview series at an astronomical figure. You accept and become a national figure. Newspapers beg for articles, and people who spend a great deal of time at dinners ask you to make speeches. By now you are too busy to appear regularly on television. The one thing left to do is an occasional play, but the Drama Department can’t afford you.

At this point you are at a crossroads. If you insist on remaining in the public eye, you will receive adulation and notoriety wherever you go: but your money will pour out on travel fares, tips and hotel bills. Not to mention paying secretaries, press agents, managers, business agents, chauffeurs, servants, fan mail, photographs, clothes and laundry bills. Now, only the regular salaries at your precarious level are paid on the administrative side of TV organizations. So you accept an administrative job.

You are mollified, at first, because your fares are paid by the company, so is your secretary, mail and hotel bills. Very little of your clothes show behind a desk, so it is merely a question of changing tops. Most of your salary goes on cigarettes; but that’s fine, as all meals are covered by the expense account.

Your ego’s appetite is satiated by issuing derogatory memos about your rival’s performance on the screen. If you manage to triplicate your memos enough, you may sell a programme idea to an unseen body called “Programme Planners.” They collapse under the storm of paper and give you some screen time.

At last you’ve come into your own. You decide you are going to conceive, direct and appear in your programme all on your own. However, your secretary, in the last stages of exhaustion, suggests you request staff to deal with the memo filled cabinets and the mass of programme aftermath. She hits upon the idea of a programme spot dedicated to the discovery of new talent. You agree and the programme is launched as A.N. Other’s Show.

At this stage your perspective goes. Your small office becomes a suite in order to absorb the new staff, the filling cabinets and the talent spotters. You find your work is (literally) cut out, to keep all these people employed. Your new talent floods the already bulging market of mediocrity. You are obsessed by the flood of revengeful memos criticising your programme. You are persecuted by viewers in full cry, because Priscilla Bushwack is not as good as their own daughters. The technicians become a nightmare of frustration against your ideas.

You lose weight running from the control room, where you direct the programme, to your position in front of the cameras. You are out of breath and you are hardly audible. Sometimes you are speechless, because the camera breaks down and you have to run to another one, which is working, but out of focus. Visually this is not very complimentary. As you are not making any sound either, viewers switch to another channel. As a result, audience reactions are very low indeed and the programme ratings positively macabre. The programme planners, who have come up for air now, take your series off the screen.

However, you have come a long way. You have had plenty of experience. You are at your peak. Astral powers in television decide you are fully equipped to interview more television addicts. You are transferred to another office, where you live with filing cabinets, harrowed secretaries, and inexhaustible telephones…’

In 1958, Jackie starred in a self-penned sitcom Trouble for Two alongside London-based Australian singer Lorrae Desmond. The series debuted in May and was given a short Radio Times write-up: ‘Take a sparkling comedienne with a flair for mimicry and satire, add a personality singer from Australia who has settled over here as one of our most popular vocalists, put them together in a London flat and confront them with the everyday problems of living, and you get the formula for a new television series. The two are, of course, Jacqueline Mackenzie and Lorrae Desmond, and their comedy series, based on their own talents and real-life personalities, promises to be something new in entertainment.' Whether or not the series was funny or whether it was because the British public were simply not ready for something new in entertainment, it only lasted for four half-hour episodes. But by that time, Mackenzie’s life had taken several different turns.

Jackie had her first lesbian affair in Savannah, Georgia, during a lecture tour in North America in 1957. Despite her ‘fling,’ she went on to marry famous author Peter Forster the following year. Speaking about her first lesbian experience she later recalled, “I didn’t see myself as being a lesbian, or her, because I didn’t look as I imagined they did, and nor did she. We weren’t short back and sides and natty gent’s suiting. I got the image from The Well of Loneliness (a novel by British author Radclyffe Hall that was first published in 1928), like we all did. There were drug stores around the States, with these pulp books, lurid stories about lesbians who smoked cigars and had orgies with young girls. I thought, where are these women? We never met anyone we knew were lesbians. There were no other books that I found about lesbians, no films that we ever saw: nothing at all.”

The marriage was over within two years as she accepted her true sexual identity. Peter Forster found out about her homosexuality and divorced her in 1962. Upon her divorce, Jackie (now going by the name Jackie Forster) went to live in Canada. In 1964, once the dust had settled, Jackie moved back to the United Kingdom and started working for Border Television. After some time, she moved in with her girlfriend and children in London. It was another five years before she came out, but when she did, she did it with the same openness and fervent conviction that had been her trademark, announcing to the world at Speaker's Corner: "You are looking at a roaring dyke." It had taken all that time for her "to get rid of the feeling there is really something rather nasty and nobody else should know about it", she said. Suddenly she thought, "How dare they?"

From that moment on Jackie fully embraced the Gay Rights Movement, holding one of the CHE (Committee for Homosexual Equality) banners nearby, vowing to never stop working for other women so they did not have to go through what she had been through. She was a proud participant in the United Kingdom’s first ever Gay Pride march in August 1971. She co-founded the magazine Sappho in 1972, the social group which also went on to become one of the UK’s longest running lesbian publications and she served on the Campaign’s Executive Committee. While the Sappho magazine’s publication ran up to 1981, the group members continued to convene regularly for many years to come, offering a place - geographically and emotionally - where, at a time when lesbians were invisible not only to the world but to each other, they could "unfurl" without fear, as Jackie put it. Her energy and dedication were second to none. She moved on to become, in the words of British human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell, "a trailblazer". Always supportive of the controversial gay rights group Outrage, which was formed to fight for what they saw as the rights of lesbian, gay and bisexual people, she delighted in the excitement of its policy of direct action. "I must do more of these," she told Tatchell, "to stop me growing into a respectable old lady."

"She had a fund of stories," recalled Stephen Leslie, the producer of The Day That Changed My Life, a programme about her life, made by the BBC in 1997. "I think sometimes she liked to make a scene; I think she enjoyed being the centre of attention. But she was also the fount of a hell of a lot of knowledge and wisdom." From 1992 until her death in 1998 Jackie was an active member of the Lesbian Archive and Information Centre management Committee (now part of the Glasgow Women's Library) and her work made a huge impact on shaping the archive. Gill Hanscombe, with whom she co-wrote Rocking the Cradle in 1981, about lesbian mothers, described Jackie as "that rare individual. She had noble instincts and the noblest of them is to fight for injustice of any kind, not just for lesbians. If she had served any cause other than lesbian rights, she'd have been festooned with honours; she would have been Dame Jackie Forster." Even though Jackie was never given the title of dame, she is fondly remembered by today’s LGBT community as “Saint Jackie of the Eternal Mission to Lay Sisters”.

"Until the 1970s," said film and television historian Stephen Bourne, who dedicated an evening to her at the National Film Theatre in 1996, "lesbians would not appear on television in actuality. They did not want to be identified. Jackie was one of the first who really came out as a lesbian on TV and raised their profile in public." London Weekend Television's 1974 access programme Speak for Yourself, the first ever to be made by lesbians and gays themselves, heralded the start of a swathe of programmes in which Forster spoke her mind and helped others to find theirs. When she was diagnosed with breast cancer, she took up the cause on behalf of breast cancer awareness.

Jackie was always available at the other end of a phone to give a word of comfort or support to others in the gay and lesbian community, and when she was approaching her seventies, she created Daytime Dykes - a purely social gathering that visited historical buildings and museums. In the week before her death, she was still working as a volunteer with talking papers for the blind.

Jacqueline Moir Mackenzie, broadcaster, editor and gay rights activist, passed away on 10 October 1998. Google celebrated her 91st birthday with a doodle on 6 November 2017 in recognition of a tireless lesbian rights campaigner and icon who led by example and truly paved a path for numerous others to follow.

Published on March 14th, 2021. Written by Marc Saul for Television Heaven.