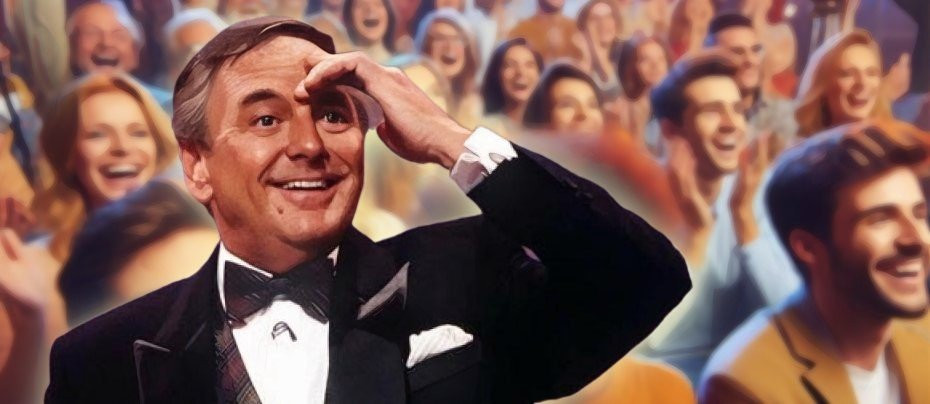

Les Dawson

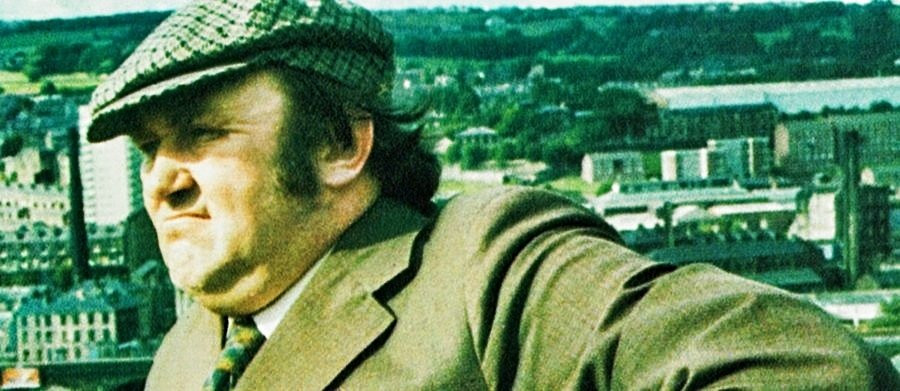

Once described as the best-loved fat man in Britain Les Dawson won his place in the national heart not for his corpulence but for his comedy which was unique-and for many years ahead of its time. So unique, in fact, that he very nearly didn't make the breakthrough into show business.

Born in Collyhurst, Manchester, on 2 February 1931, Les Dawson grew up with a poverty-stricken but loving family. His father was a lowly-paid labourer who would supplement his income by playing cards or hustling a game of billiards. But the Dawsons would often find themselves having to grab their possessions and do a 'moonlight flit' to avoid the rent man. This meant a constant change of schools, although from an early age Les displayed signs of above average intelligence and a great love of words. At primary school he wrote essays and poetry but for the most part kept it a secret from his school mates, preferring to be 'one of the lads'. Years later Les recalled an incident in class where a teacher, Bill Hetherington, singled him out for his lack of application in geography and maths. His punishment was six strokes of the cane - much to the amusement of his fellow pupils. But later, Hetherington read to the class an essay that Les had written entitled 'A Winter's Day.' The teacher remarked at how good the story was and informed everyone that Les had 'the talent to be a fine writer.' It was a crucial moment for Les and possibly shaped his future.

Les spent the war years with his mother, his father serving in the desert with the Eighth Army. An unexploded bomb forced them into a nearby rest home as that part of Lancashire came under heavy air-raids, and at the age of twelve they were forced to move again. But his education was coming to an end and, as was common in those days, Les left school at fourteen and applied for a job with the local Co-operative Wholesale Society. He found the job dull and so turned to becoming an apprentice electrician. When National Service came it was a relief to Les, a way out of the hum drum life he was leading.

On being demobbed Les returned to Manchester where he eventually began writing seriously, submitting essays and poetry to various publications. "I was trying to write essays. Things like "Grimy hunched warehouses clutching the skyline with dissipated profiles, glazing eyeless upon pitted streets." He later wrote. "I never, for one moment, thought I might have a slight problem making a living out of writing such stuff. I never thought about who might actually buy this writing. I just thought you wrote and somehow got paid." Around this time Les decided to move to Paris, a bold and risky decision but one he later reflected on: "I wandered down Monsieur Le Prince, a small winding street on the Left Bank and I walked into a bar and there was a beautiful piano. I just sat down and started playing it. And this Madame came out and offered me a job playing piano, late nights. It was the best job I ever had because she plied me with red wine. But nobody came in at all. I couldn't understand the point. The thing was, that bar was just a front for a brothel." It was during that time that Les developed a unique piano-playing style of his own. He began playing deliberately off-key, and to his delight it amused those drifting in and out of the brothel and he started to get a small following. But life in Paris wasn't financially rewarding and by now Les had stopped writing. After four months he returned to Lancashire.

Back home, Les got a job playing piano in a local pub and entered a talent contest. He performed dressed as Quasimodo, complete with hump, crouched at a grand piano, and playing off-key in the style that had gone down so well in Paris. He left the stage to the sound of his own footsteps. His showbiz career at an end before it had even started; Les became a door-to-door Hoover salesman. Cold-calling actually enabled Les to develop a patter and gave him the opportunity to improvise. But selling wasn't something that came naturally to Les and these were austere times-Hoover sales were not exactly booming. Les gave up the job and once again decided to travel. This time, though, he set his sights on London. London, like Paris, failed to live up to Dawson's expectations. Before the first week was out he was washing dishes in a café by night, and scouring theatrical agencies by day. He soon returned to Manchester where he was accepted as a cub reporter for the Bury Times but the appeal soon wore off when he was given menial stories to write. Eventually, Les decided to resurrect his very brief stage career by taking his act on the northern circuit of working men's clubs. An important source of entertainment, working men's clubs became hugely popular in the second half of the 19th century, often springing up in the side rooms of local pubs. Here, manual workers had the chance to have a few pints, a hearty sing-song and be entertained by anyone wishing to 'have a go.' By the 1950s the club circuit was a great training ground for up-and-coming or would-be entertainers who numbered in their thousands. As well as amateur performers the clubs paid for professional performers too. The audience were encouraged to show their appreciation for their favourites as well as their disdain for the acts they didn't like. Unfortunately for him, Les fell into the latter category.

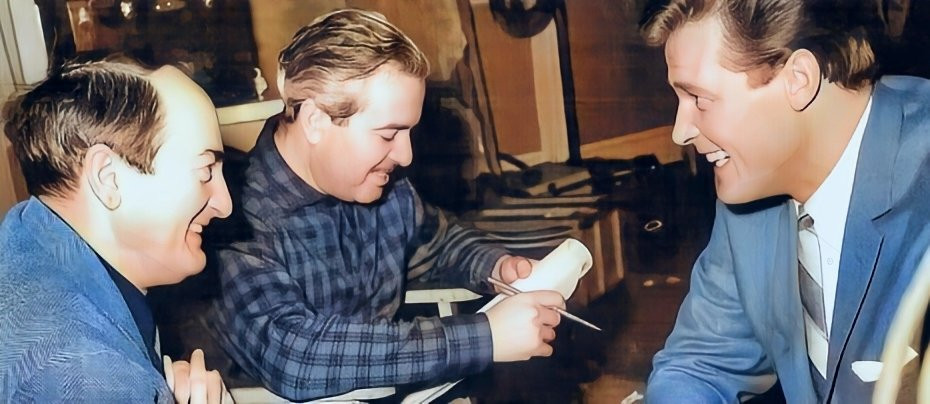

Les Dawson's club circuit act was, like the early talent contest he entered, somewhat surreal. It was met at times with open hostility. But over the years he learned his trade and what he could get away with and where he could get away with it. As the 1960s dawned, Les was working the club circuit by night and selling Hoovers by day, having returned to the sales job as a means to support him-self. He offered his own surreal writings to radio and television producers and they in turn ignored them. Eventually though, one letter did find its way onto the desk of Manchester's Head of Light Entertainment, Jim Casey. Together, with light entertainment producer Mike Craig, he went to see Dawson's act. The audience that night was one that didn't appreciate the Dawson humour. Fortunately, Jim Casey did. Casey offered Les some short spots on the BBC's Light Programme. He was convinced that Dawson's wordplay, which came from his love of the English Language, would come across more effectively on radio. "Les loved old English novels," Casey would later say. "I remember him one day saying to me 'Listen to this, Jim, isn't it wonderful?' And he read this phrase: 'I will render you asunder with a ball from my horse pistol.' He always used these kind of phrases and the fact that he put them into ordinary everyday situations about the wife or mother-in-law, that's what made him so different. There was no one else on Earth who was doing anything like that."

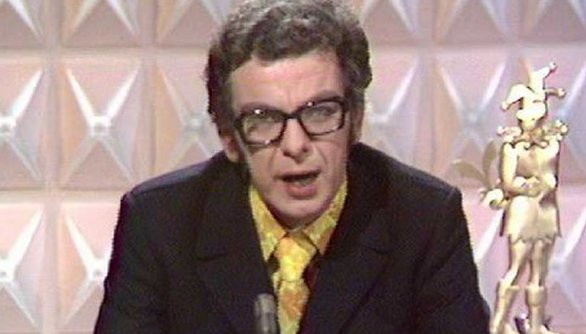

Dawson's wife, Meg, who he had met on the club circuit, encouraged him to apply for the television talent contest Opportunity Knocks. He passed the audition and in March 1965 appeared in front of the cameras and in millions of homes in Great Britain. Seated at a piano, Les went into a routine that he had written him-self: "Tonight I would like to play you something from Chopin…but I won't. He never plays any of mine. Then I toyed with the idea of playing Ravel's 'Pavane Pour Un Infante Défunte', but I can't remember if it's a tune or a Latin prescription for piles. Anyway, before anyone slides into a coma I'll play a song that was written by Bach as he lay dying. (He plays one note). Then he died." Although Les failed to win the postal vote he had made a huge impression. He was booked for an appearance on another ITV light entertainment show, Blackpool Night Out, and by all accounts - on a bill that starred Dickie Henderson and Cliff Richard, Les stole the show. Suddenly, Les Dawson's career took off and everyone wanted to book him.

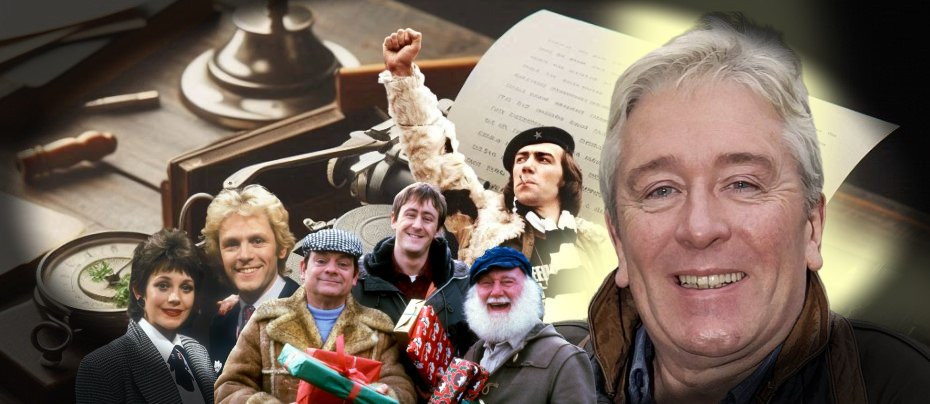

By the end of the 60s Les Dawson was a household name. A chance meeting with John Duncan, a producer at Yorkshire Television, led to an offer of his own series, Sez Les. Described by Mark Lewisohn in his Guide to TV Comedy as "his definitive TV show," the first two series no longer exist in the archives, the master tapes having been re-used, lost or taped-over. The series produced two of British televisions most memorable characters, Cissie and Ada, two Northern housewives who enjoy nothing more than a bit of juicy gossip in conspiratorial tones whilst sipping tea and lifting their considerably large bosoms. Roy Barraclough, who played Cissie explained how the characters came about during breaks in the studio recording of Sez Lez: "Les and I used to go into this routine because he was a big fan of Norman Evans (a 1940s variety and radio performer), as was I. So we used to go into this routine (and) the producer said, "That's a brilliant idea. Why don't you do that as a sketch and do the thing in drag?" At first both performers refused but decided to use the characters to 'warm-up' the live audience before the recording of each show, When they saw how well it went down they decided to add the characters to the series.

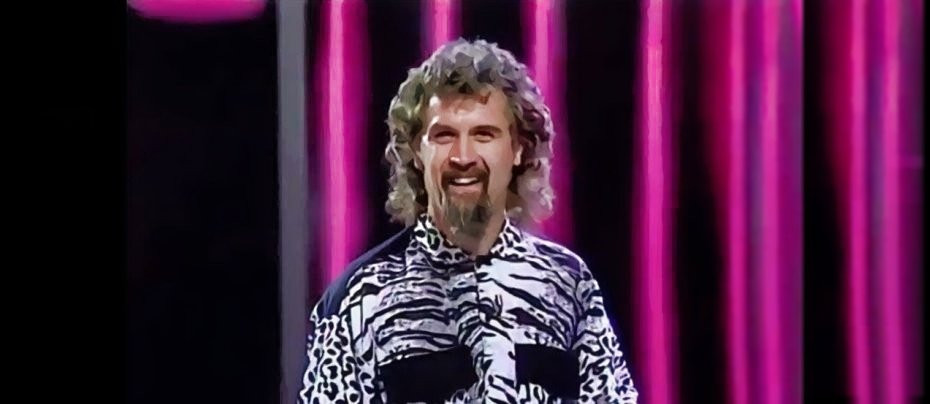

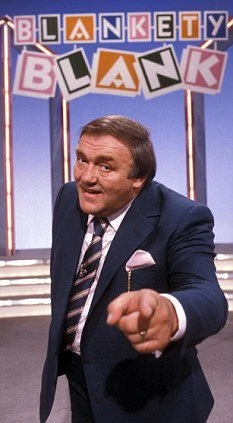

Sez Les ran from 1969 to 1976 - eleven series in total. In between there were other one-off specials such as a Galton and Simpson penned sitcom Holiday With Strings, a sketch show called Sounds Like Les Dawson and two festive specials in 1974 and 1975; Les Dawson's Christmas Box. It wasn't until Dawson's Weekly in 1975 that Les fell out of favour with the critics. The series came about following the success of Holiday With Strings. Galton and Simpson would write seven more one-off sitcoms for Les under the same title which was a play on the classified-ads newspaper Dalton's Weekly. It was familiar territory for Galton and Simpson who had done the same before with Comedy Playhouse, except that series featured a different headline cast each week. In Dawson's Weekly it was only the support cast that was for each episode - all except for Les and Roy Barraclough. But the critics panned the series from the first episode to the last. Les did one more series for Yorkshire Television, four one-hour specials under the title Dawson and Friends. In 1978 he signed with the BBC to do The Les Dawson Show, a series that ran until 1989. In 1984 he took over from Terry Wogan as host of the popular gameshow Blankety Blank.

During that period Les had to deal with a tragedy in his life. His wife, Meg, who had been diagnosed with cancer, passed away on 15 April 1986. Les withdrew from the gaze of the spotlight to concentrate on bringing up his children. Always a heavy smoker and drinker, Les began to frequent the St Ives Hotel in Lytham, where he immersed himself in misery and alcohol. It was here that Les met and fell in love with Tracy, the barmaid who would lend a sympathetic ear to his outpourings of grief. Their affair and subsequent marriage further fuelled the frenzied disdain of the press that had turned against him with Dawson's Weekly. But Les and Tracy stuck together until the press mellowed. Nevertheless, the pressure took its toll and Les suffered a heart attack. His recovery was steady and Les gradually returned to work, doing cruise ships and the BBC offered him the role of host on a revamped version of Opportunity Knocks. Once again the critics sharpened their pens ready to tear the series apart.

Les married Tracy on 6 May 1989. They had a daughter, Charlotte, who was born on 3 October 1992. Les, whose television career was deemed to be on the decline, was enjoying huge success in pantomime and made a stand-out appearance on the Royal Variety Show. But Les's health was still a cause for concern. He almost suffered a severe heart attack at the beginning of 1992 caused by his lungs being filled with fluid. Had it not been for the emergency team attending the Wimbledon theatre that night, it might have been his farewell performance. His doctor told him in no uncertain terms that he didn't want him to slow down his work - he wanted him to stop altogether. But Les ignored the doctors warning and continued to perform. One of his last television appearances came on 23 December 1992, when he appeared as the subject of This Is Your Life. On 10 June 1993, at a hospital in Whalley Range, Manchester, Les Dawson had just finished a check-up for insurance cover for a film role and was waiting for the results with his wife when suddenly suffered a fatal heart attack. He was 62.

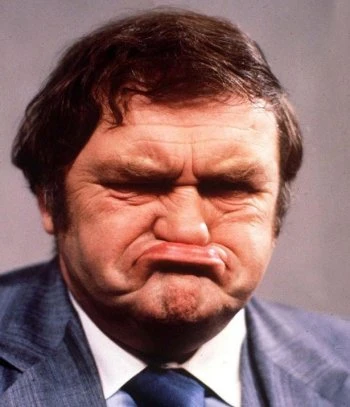

As well as his radio, screen and stage work Les Dawson also produced 12 books including a Chandler pastiche, Well Fared, My Lovely and his autobiography, A Clown Too Many. Revered by his peers as much as by his public, Dawson was voted thirty seventh in the top fifty comedians of all time by fellow comedians in the Comedians' Comedian, a three hour television programme broadcast by Channel Four on 1 January 2005. On 23 October 2008, 15 years after his death, a bronze statue immortalised Dawson in the ornamental gardens next to the pier in St Anne's-on-Sea, Lancashire, where he had lived for many years. 1 June 2013 saw ITV broadcast Les Dawson: An Audience With That Never Was. The programme featured a supposedly 3-D projection of Dawson, presenting some of the content that was planned for a 1993 edition of An Audience with Les Dawson... but which went unused due to his death two weeks prior to recording. Michael Hogan, TV critic for The Telegraph was left unimpressed with the technical wizardry used to bring the show to the screen but noted that it was: "rescued by Dawson himself, whose wit rang down the decades. He rattled out mother-in-law gags and gurned with that rubbery bulldog face. Best of all, there were copious clips of his "Cissie Braithwaite and Ada Shufflebotham" routines with Roy Barraclough, the cross-dressed pair gossiping like fishwives and silently mouthing more "delicate" words, before hitching up their ample bosoms. Cissie and Ada really were three-dimensional. " And so was Les Dawson.

Published on February 20th, 2019. Written by Laurence Marcus (2014) for Television Heaven.