Gerry Anderson

"Here I was ready to make 'The Ten Commandments' and they were asking us to work with puppets!"

There are very few modern day television storytellers whose tales span the generations. But each generation of children from the 1950s to the present day are familiar with the name Gerry Anderson. You don't have to be "of a certain age" to have marvelled at the wondrous offerings that Anderson and his talented stable of puppeteers and animators have bought to the screen. Gerry Anderson was to television what Walt Disney was to the movies. But for a man who enthralled generations of both adults and children down the years, his own childhood had a less than fairy-tale start.

Born Gerald Alexander Abrahams on 14 July 1929, Gerry was the second son of Joseph and Deborah Abrahams. After suffering from recurring anti-Semitism at school, the family changed the family name to Anderson. From an early age Gerry Anderson showed a flair and imagination fuelled by his love of the cinema which he visited weekly, usually accompanied by his mother, to see the latest releases. In the meantime, Gerry's brother, Lionel, had joined the RAF as a pilot and was sent to America to do his basic training. On his first tour of duty Lionel undertook thirty missions over the most dangerous air space in the world. Lionel often wrote to Gerry and in one particular letter he enthused over the amazing aerobatics he had witnessed, performed by planes at a nearby airfield to where he was stationed. The airfield was called Thunderbird Field.

Anderson’s love of the cinema burned bright in his desire to work in movies, but not as an actor, as it was his yearning to work behind the cameras rather than in front of them. After leaving school he sent off a continuous stream of letters to film companies and studios in search of employment, and eventually received a response from the Ministry of Information offering him a placement with their Colonial Film Unit. Anderson then applied for a vacancy at Gainsborough Pictures, who were one of the biggest independent filmmakers in the country.

In 1947, he was called up to do his National Service. Anderson was sent to Cranwell Radio School where he passed out with the rank of Leading Aircraftsman. It proved to be very influential on his later career and an incident in his final year with the RAF also had a profound effect on him.

Whilst working in the radio tower a message came through that an aircraft with a damaged undercarriage was about to attempt a life or death landing. After a tense approach the pilot managed to bring his aircraft down safely with little injury to himself or his crew. The incident stayed with Anderson for many years and formed the basis of his first Thunderbirds story Trapped in the Sky.

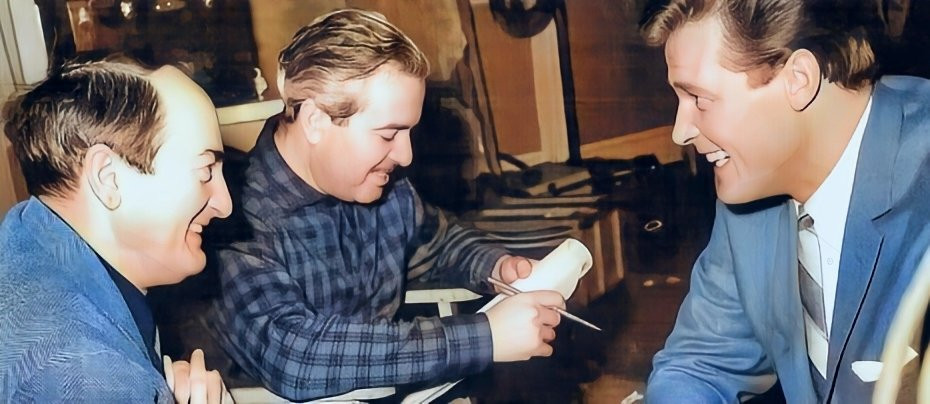

On completion of his National Service Anderson went to Pinewood Studios as a dubbing editor. After a brief time at Elstree he moved on to Shepperton. By 1955, he was working for a small production company based in Taplow, Buckinghamshire. Polytechnic Films was a relatively new company that had been formed specifically to supply programmes to the embryonic Independent Television network. Anderson had been invited to join as a director and quickly struck up a good working relationship with cameraman Arthur Provis. By 1957 Polytechnic had gone into liquidation and with the prospect of unemployment looming, Anderson and Provis decided to form their own production company. They took on three of Polytechnic's existing employees from the art department, Reg Hill who had a career as an artist before going into films and John Read who had done his National Service with the RAF as an airframe fitter. 30 -year-old secretary Sylvia Thamm completed the line-up. They called the company Pentagon Films, but after making a few TV commercials they too went bust. Undeterred, they set up AP Films (Anderson/Provis) and rented space in an Edwardian mansion in Maidenhead, Berkshire. They installed a phone and waited for their first big order. Nothing happened. Six months later, with nothing further happening, the money began to run out and all had to take other jobs to keep the company afloat. Then the phone rang.

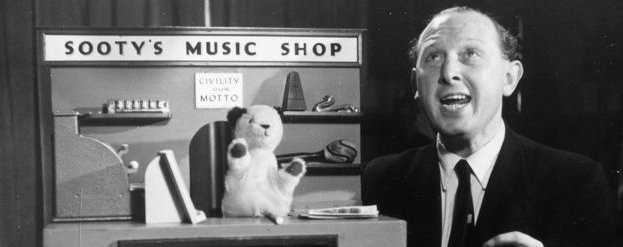

Roberta Leigh, a columnist on the Daily Herald and a writer of romantic novels and children’s stories and her colleague Suzanne Warner had been asked by the Associated Rediffusion television company to find a production company to shoot a series of Leigh's creation, Twizzle. The budget for the series was very modest and Leigh and Warner knew that their only chance of getting it made cheaply was by finding a company hungry for work. Fortunately for them, AP Films was such a company. Anderson later recalled: "Here I was ready to make 'The Ten Commandments' and they were asking us to work with puppets!" Although somewhat underwhelmed at the prospect of making a children's puppet series, there was no other offer of work, so they reluctantly took on the project at a very modest budget of £450.00 per episode.

At that point television puppets were often grotesque looking creatures (even the cutest of them), jumped around very obviously on strings, often had funny voices or were completely mute (their thoughts and actions related by a story-teller) and were completely static as far as eye movements and facial expressions were concerned. It’s no wonder that Anderson was unimpressed. But he decided right from the start that if he was to make a puppet series, he would make the best puppet series possible.

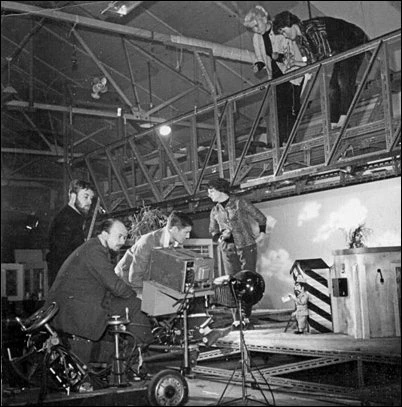

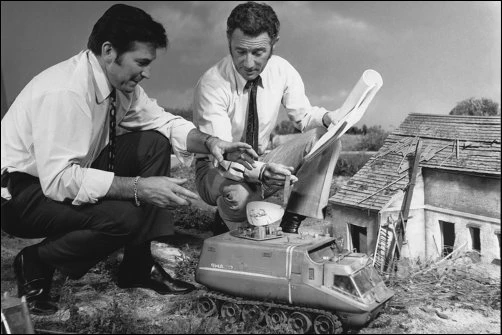

With Art Director Reg Hill, Anderson decided to add a number of film technique elements. Details were added to the set and during filming Anderson employed cuts and close-ups, all of which he had observed in the films he so loved but which were unheard of in a children's puppet series up to that point. Another area of improvement was how the puppets were operated. Anderson had observed how the shadows and sometimes even the hands of the puppet operators would sometimes be caught on camera. However, if the operators were placed higher above the set this would eliminate the problem. To this end, a gantry was erected twelve feet above the studio floor. For the puppeteers to see what they were doing Anderson bought a new lightweight camera that had just come onto the market. He rigged it up to form a device that became known as Video Assist, a brilliantly innovative technique that involved attaching the new camera to the movie camera in such a way that whatever the movie camera saw was relayed to monitors on the gantry, or anywhere else on the set. The method was soon adopted by the film industry worldwide.

The Adventures of Twizzle was first broadcast on 13 November 1957 at 4.30pm. The television series was so well received that A-R wanted another. Roberta Leigh, through her own newly formed company, Pelham Films Ltd., approached Anderson again to make 26 episodes of a brand-new puppet series called Torchy the Battery Boy . With an increase in the budget Anderson had the opportunity to really push the boundaries and see how much further they could go with the puppet series format. Delighted by the results, Roberta Leigh asked for 26 more. However, Anderson and Provis had not enjoyed the experience of working with Leigh and were especially put out when they discovered how much she was earning from the series compared to what she was paying them.

By the time she approached them for a third series they had already decided to produce their own puppet series. With a modest amount of money in the bank and an idea given to them by their music composer, Barry Gray, they set about making a pilot episode for a western called Four Feather Falls . However, a disagreement between Anderson and Provis over the purchase of a property eventually led to the pair parting company.

Four Feather Falls was AP Films' most ambitious project to date, with more detailed sets and more sophisticated puppets. Anderson and his team experimented with electronics to match the puppets mouth movements to the dialogue. The head of the puppet was fitted with a solenoid connected to a tungsten wire and pulses were fed down it from a tape recording of the actors' voices. This technique was one of the earliest developments for a process that Anderson eventually named Supermarionation.

Anderson took the pilot to Granada Television who commissioned 34 episodes. As a result of his new found success he decided it was time for AP Films to move into larger premises, and quickly secured a lease on a former warehouse at Ipswich Road on the Slough Trading Estate.

The first episode of Four Feather Falls was shown in the UK just two days after Gerry Anderson's previous series Torchy the Battery Boy had begun in the London area. It debuted on Thursday 25 February 1960 at 5.00pm and featured on the cover of that week's edition of TV Times. With the success of Four Feather Falls to add to Anderson's impressive CV of children's puppet series, AP Films fully expected Granada to ask for more. Instead, on delivery of the last programme Anderson was handed a cheque and met with stony silence. In the meantime, he and his crew had already worked out a concept for their next series. They even had a name for it.

It was called...Supercar.

During one of his periodic meetings with Lew Grade, the TV mogul said to Anderson "I'm going to buy your company."

Anderson was invited to make a low-budget b-movie by Stuart Levy and Nat Cohen of Anglo Amalgamated. Anderson saw this as a great opportunity to break into serious movie making. The budget was a meagre £16,250 but nevertheless Anderson immediately commissioned a script, which was eventually called Crossroads to Crime. The film was shot in the vicinity of AP Film studios and was a standard crime-thriller that starred Anthony Oliver and quickly disappeared without trace.

Soon after the movie, Anderson was offered work by Nicholas Parsons' own production company to make a series of commercials on a shoestring budget for Blue Cars Holidays and one of them won a prestigious Grand Prix prize at the first ever British Television Commercials Awards in 1961. Despite all this activity, the future for AP Films did not look all that promising. Anderson had already decided that the company had to go into voluntary liquidation when he received a phone call from a man called Connery Chapel who agreed to accept some shares in the company in return for an introduction to the Deputy Managing Director of Associated Television, Lew Grade. At this point Grade was beginning to build a huge reputation for himself and would go on to become one of the most influential executives in the history of British TV. Anderson arranged a meeting with Grade.

Arriving at Grade's office, Anderson pitched the idea for Supercar. Grade was impressed but exploded into a temper when Anderson quoted him £3,000 per episode. "I'll give you an immediate order for twenty-six episodes provided you cut the budget in half" he told Anderson. Anderson returned to his office and he and his crew worked through the night trimming as many unnecessary costs as possible, even restricting his staff to 2 cups a tea a day instead of 4! By morning they realised it was impossible to meet Lew Grade's target. Anderson returned to Grade's office the following morning and told the executive that no matter how hard they tried the best they could get the budget down to was a third. "Okay," said Grade, "you've got deal."

The idea for Supercar was of a craft that could travel on land, under the sea, and through the air and was far more fantastical and futuristic than anything AP Films had come up with before or had ever been attempted in a children’s puppet series. Anderson had already laid the foundations for the process known as Supermarionation, and with Supercar it appeared on screen for the first time. The voice synchronisation technique was only part of it and added to that were interchangeable puppet heads so they could be seen with different expressions, wires that were painted the same colour as the background rendering them almost invisible, and a host of film making methods such as back projection, location filming and full orchestral music scores were added.

The initial 26 episodes of Supercar began broadcasting on the ATV network on 28 January 1961. In the meantime, Lew Grade had successfully sold the series to the USA, where it grossed $750,000 in its first eight weeks. Eventually it was broadcast coast to coast by 107 stations and became the country's top-rated children's programme. It was the first ITC show to be sold to America and secured the future success of the company as well as Gerry Anderson.

Another first for Anderson was AP Merchandising, a company set up purely to cash in on the merchandising of his product; something that these days is taken for granted but hardly heard of in 1960. AP Merchandising produced a range of ‘Supercar’ books, dolls, toys, games and play-sets and within three years could boast retail sales exceeding £750,000.

During the filming of Supercar, Gerry and Sylvia Thamm were married.

For his next series Anderson decided to pump up the science fiction element. Anderson's proposal for the new series, to be called Century 21, was taken up without hesitation by Lew Grade. The series title was changed to Nova X 100 before going into production as Fireball XL5 - the title inspired by the motor oil Castrol XL.

This being the most elaborate Anderson series to date, the talented backroom crew created a special effects studio which was added to the existing one, and it was here that Space City was built, enabling close-ups to be shot of the spaceships being fired from their rocket bases. On its broadcast in the UK, the series reached number seven in the TV charts and when Lew Grade sold it to the USA it performed well beyond anyone's expectations on the NBC Network.

It was now, during one of his periodic meetings with Lew Grade, that the TV mogul said to Anderson "I'm going to buy your company." Anderson’s first thought was “What a nerve!” When he saw the cheque that Grade had written him for the purchase he thought “What a good idea!”

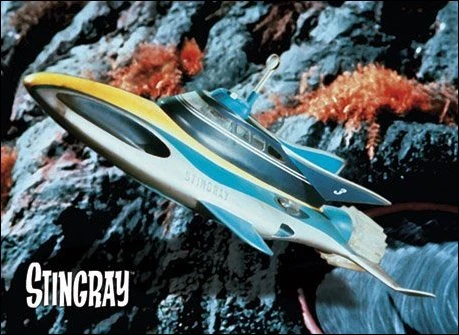

Grade's buy-out stipulated that Gerry Anderson would continue to run AP, and one of his first decisions was to lease and equip larger premises on another part of the Slough Industrial Estate, on Stirling Road. This housed three shooting stages, production offices, a preview theatre and 12 cutting rooms. Here he would shoot his next series; Stingray.

Gerry Anderson's third venture into Supermarionation, and his first to be filmed in colour (even though it could only be shown in black and white on its first run in the UK), Stingray was possibly the first puppet series to win the appreciation of an adult audience.

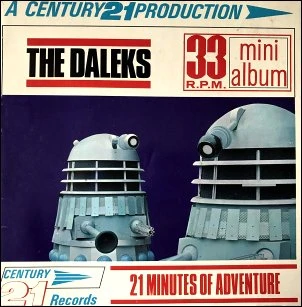

The series proved to be a worldwide success with manufacturers clamouring for licences. One of the biggest merchandising successes for AP was the launch, on Wednesday 23 January 1965, of a weekly colour comic called TV Century 21. Selling for 7d which was slightly higher than the average children's comic then available; TV21 was, like all of Anderson's puppet series, far superior to that of its competitors. Printed on high quality smooth paper (as opposed to the newsprint type) it also included a number of other TV shows that were popular with youngsters, such as My Favourite Martian , Get Smart! , Burke's Law, The Munsters and, in something of a coup for the comic, The Daleks (but not Doctor Who). The comic proved such a big hit that a year later, Lady Penelope, aimed specifically at girls, was added to AP's catalogue and between them the two comics combined circulation totalled 1,300,000 copies a week, a phenomenal total that has not been bettered by any British comic to this day.

Encouraged by the popularity of the comics, Gerry Anderson instigated Century 21 Records in association with Pye Records to produce a series of 21-minute EP's featuring abridged versions of the TV episodes of his shows, usually narrated by one of the principle characters. They even managed to secure a licence from the BBC to release a record of a broadcast Doctor Who episode (episode 6 of The Chase).

Even whilst Stingray was still in production, Anderson was making plans for his next series. The working title for it was International Rescue, although he later decided on a punchier title, inspired by the airfield near where his brother had trained. It was to be called Thunderbirds.

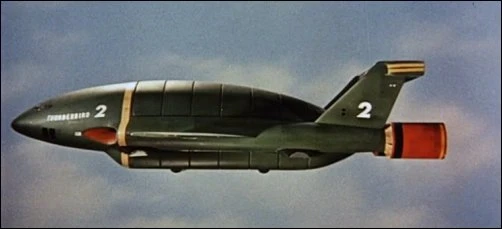

The show's central premise was stunning in its simple and economical effectiveness. Operating from their base located on an isolated atoll in the Pacific, Millionaire ex-astronaut Jeff Tracy and his five sons, Scott, John, Virgil, Gordon and Alan, formed the core of the altruistic secret organisation "International Rescue". The premise for the show was influenced by Anderson's previous experiences but also by a German mining disaster where a group of miners had been trapped underground and the efforts made to save them. Anderson pondered the idea of a secret organisation that would turn up just in the nick of time when all hope seemed lost, and using ultra-modern rescue equipment, and fantastic, futuristic machines, raced against the clock to save the day.

With a budget of £25,000 per episode, filming began in the late summer of 1964 and by late September, nine of the proposed 26 half-hour episodes were 'in the can.' The opening episode Trapped In The Sky was then screened for Lew Grade who on seeing it exclaimed, "This isn't a television series, it's an epic!" and promptly ordered each episode to be doubled in length and increased the budget to £38,000 for each hour. New footage had to be shot for each of the 'completed' episodes and by the time the first had debuted on ITV, Grade had commissioned a further six episodes along with a £250,000 feature film.

Public response to the series was phenomenal, and the series immediately won £350,000 in overseas sales.

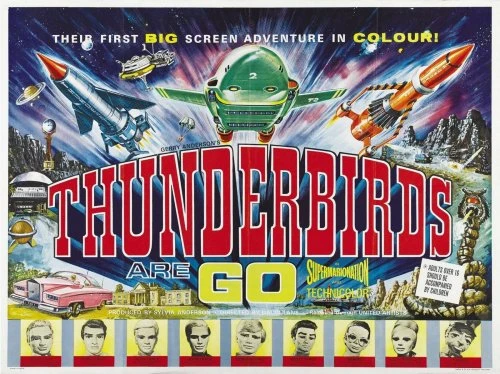

Unfortunately, America decided not to show the series in its full 60-minute version and each show was split into thirty minutes with the first half hour finishing on a cliff-hanger. As a result of this, Thunderbirds wasn't the hit in America that it was around the rest of the world (it sold to 65 countries) and, even though it was shown coast-to-coast, one has to wonder if this influenced Lew Grade's decision not to renew it for a second series. However, before this Thunderbirds was transferred to the big screen. Thunderbirds Are Go was premiered at the London Pavilion in Piccadilly Circus on Monday 12 December 1966. Everyone was positive and upbeat about the film and the next day the press echoed these sentiments. Till the day he died it remained a mystery to Gerry Anderson as to why it performed so poorly at the box office.

Despite the setback of poor box-office returns, Anderson could content himself with two very high profile awards that year. In May he was awarded a Silver Medal for Outstanding Artistic Achievement from the Royal Television Society, and later he was made an Honorary Fellow of the British Kinematograph Sound and Television Society. By its end in 1966, Thunderbirds had become something of a national institution. The Tracy's, along with the likes of such characters as their London based agent, Lady Penelope, and her shifty Cockney chauffeur, Parker, had gained a place in the collective consciousness that has endured to this day.

At the end of the production of the 22 episodes Anderson attended a meeting with Lew Grade, fully expecting to talk about the second series of Thunderbirds. Instead, he was stunned when Grade began the conversation with, "I think it's time we made a new show."

Grade shouted for the lights to go up in the screening room and stormed, "Cancel It! I don't want any more made!"

Lew Grade’s decision came as a serious blow to the Century 21 Organisation. Large amounts of money had been tied up in merchandising and a factory in Hong Kong had been financed to produce Thunderbirds toys in a significant quantity. But when the news broke that there would be no new series, orders were cancelled all round the world. "We were caught with our pants down", said Anderson. "We had a lot of merchandise aboard ships in transit." Anderson claimed that it was 'a catastrophe' that marked the beginning of the end. "The infrastructure was too big to sustain without a hit like Thunderbirds. Eventually, large amounts of toys were simply dumped." Once again Anderson had to come up with a new series.

Returning to a more fantastical science fiction element, Anderson came up with a plot that involved Earth being under threat from an alien menace, bent on the total destruction of the human race. The new series was to be called Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons.

With a budget of £1,500,000 for the series, filming began on Monday 27January 1967. Each episode took two weeks to shoot. During filming of 'Captain Scarlet', Anderson was also filming the second Thunderbirds movie, Thunderbird 6 and this caused delays to the 'Scarlet' shooting schedule. Therefore, instead of completing all 32 episodes in eight months the last episodes were not ‘in the can’ until the end October 1967. It's hard to say whether Thunderbirds was just too hard an act to follow, whether Anderson, who was busy on other projects at that time, didn't put as much effort into the series, or simply that Captain Scarlet wasn't as good as previous Gerry Anderson series. And in another blow, the new Thunderbirds movie did even worse at the box office than the previous one. Despite this, Anderson was given another chance to make a feature film. It would be his second feature with live actors.

Sylvia Anderson said that Doppelganger, as the movie was called, was originally being prepared as an hour-long drama for ATV. "We'd had a call from Joe Douglas of ATV who was looking for hour long dramas, so I pulled it out of the drawer, but I felt it was too good to give away, so I thought, 'Let's make it into a film.'" Gerry wanted David Lane to direct the movie, but the producer insisted on a 'bankable' US director. Robert Parrish was hired, but not to the liking of Anderson. It was clear from the start that Gerry Anderson and Parrish were not going to get on. Anderson became frustrated when the director deleted whole scenes without discussing the decision first. Anderson wasn't the only one who wasn't entirely happy with the director, as Sylvia Anderson remembered some years later. "I don't think Robert Parrish was a brilliant choice as director. They wanted an American so they could finance the film, but I think his direction was uninspired. We had a lot of trouble getting what we wanted from him." Once again Anderson's attempt at making a box office killing only led to disappointment and the movie failed to be a hit with the public even though it won the Hollywood Blue Ribbon Award for Best Screenplay (1969) and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Special Effects.

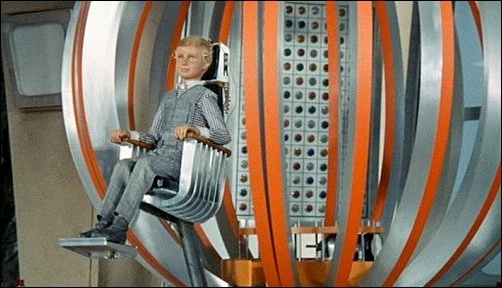

By the time Doppelganger was released Gerry Anderson was already involved with a new puppet series for television. Inspired by an article he had read on how the human brain is controlled by electrical impulses, Anderson began to toy with the idea of recording people's memories and thought patterns and transferring them to another's brain. This was the basis for Joe 90. Anderson's ninth consecutive TV puppet series and the sixth in the ever expanding Supermarionation stable.

But Joe 90's appeal with the adult section of the audience which had been captured by Thunderbirds and, to a lesser extent, its follow up series Captainfollow-up Scarlet and the Mysterons suffered from the decision to make the all-important central character a child. As a result, Joe 90 is remembered as one of the Anderson stable's lesser series. Anderson certainly had less to do with this series, and a lot less resources were piled into it. Very few new models were created for Joe 90. Consequently, in some episodes, instantly recognizable faces are seen such as Captain Black, Colonel White and even Captain Scarlet himself.

Many TV stations, it seems, were less than enthusiastic about the series. It debuted on ATV Midlands and Tyne-Tees at the end of September 1968 and appeared shortly after in London on LWT and then elsewhere in the Southern and Anglia regions before screenings in the Harlech and Channel regions on Christmas Day. Inexplicably, Granada debuted it with episode 8, missing the all-important opening episode which didn't appear until several weeks later. Yorkshire Television didn't show the series for 13 years!

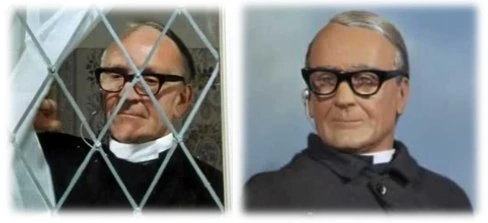

Just two days after principal photography had concluded on Joe 90, Gerry Anderson's next puppet series was in production. The Secret Service was inspired by a chance meeting between Gerry and actor Stanley Unwin at Pinewood Studios during production of Doppleganger. Unwin had found fame by twisting words into a nonsense language, which he called Unwinese, on radio and later TV in the 1940s and 1950s. Born in Pretoria, South Africa, it was his mother who unwittingly provided him with the inspiration for his language. When she tripped up one day, she told her son that she had "falloloped over and grazed her knee clapper". Unwin developed his unique language by reading fairy tales to his children, an example being: "Once a polly tie tode, a young lad set out in the early mordee, to find it deef wisdom and true love in flower petals arrayed."

Originally, it was intended to make the series live action, but production costs prohibited this. Instead, Anderson went for a mixture of live action and puppetry. A puppet of Unwin was made and the series went into production on Tuesday 20 August, 1968. In it, Unwin played an old-country vicar who was furtively a secret agent for BISHOP-British Intelligence Service Headquarters Operation Priest. It was an awful concept and made for an equally awful series. Thirteen episodes were in the can when Anderson took the pilot to Lew Grade. All was going well until Unwin's character started to speak-Grade shouted for the lights to go up in the screening room and stormed, "Cancel It! I don't want any more made!" And with that comment the Supermarionation productions of Gerry Anderson were bought to a close.

(Harry) Saltzman offered Anderson the chance to write the script for the next James Bond movie, Moonraker.

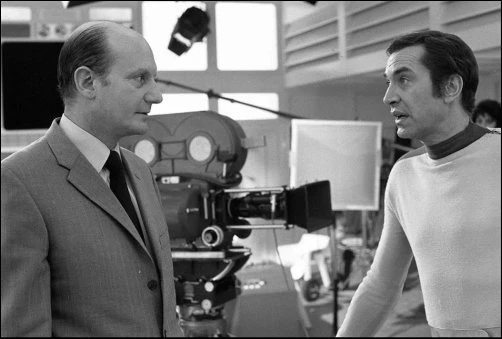

With the end of Supermarionation Lew Grade offered Anderson the chance to realise a long awaited ambition by making a full live action TV series. Lew Grade agreed to bankroll UFO to the tune of £100,000 per episode. Set in 1980, the Earth is visited by a humanoid race of alien visitors from Alpha Centauri. Their people are dying and the only way to help them is by kidnapping humans and stealing vital organs for transplant. Earth's last line of defence is the worldwide security organisation SHADO (Supreme Headquarters Alien Defence Organisation), led by USAF Commander Ed Straker.

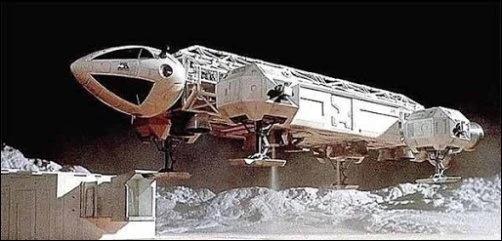

The usual Anderson hardware was designed for the show including the Skydiver fleet, which were able to launch a powerful supersonic front section called Sky One. There were custom designed vehicles for SHADO's operatives as well as more heavy-duty equipment such as Seagull supersonic passenger transport jets, Albatross long-range rescue aircraft, and the SHADAIR fleet. When the series aired it seemed broadcasters were unsure whether to promote it as an adult or children's series. As a result, it meandered between Saturday morning and late night 'graveyard' slots until, eventually, a planned second season was cancelled to make way for the Anderson's next project, Space: 1999.

During the production of UFO, Anderson was invited to the offices of Harry Saltzman and Cubby Broccoli, the owner of Eon Films, the company that made the James Bond movies. It was Saltzman who offered Anderson the chance to write the script for the next James Bond movie, Moonraker. Saltzman was so impressed by the script that he offered Anderson $20,000 for it. He turned Saltzman down because he felt that by accepting it his involvement in the film would come to an end and he desperately wanted to see the project through to conclusion. Saltzman, however, broke off all contact with Anderson and the project was never referred to again. Several years later, when The Spy Who Loved Me was released, Anderson noticed significant similarities between that James Bond film and his originally submitted script. Anderson threatened to sue Eon Films, but when they threatened to counter-sue he backed down. Eventually the company made an out-of-court settlement and Anderson got a meagre £3,000 for his trouble, but only on condition that he hand over his story outline and destroy all copies.

As production on UFO was drawing to a close Anderson formed a new company with Sylvia and Reg Hill. They called it Group Three and their first commission came, naturally enough, from Lew Grade. But the format for the new series was a total departure for Gerry Anderson. "I had one of my regular early morning meetings with Lew and on this day he handed me a piece of paper and asked me to read it." The paper contained a brief outline for a new action-adventure series. It read: 'There is a small group of private detectives who are able to work more efficiently because they are operating outside the law.' Grade immediately made an initial order of 26 episodes.

Gerry Anderson and Reg Hill developed the concept of a brotherhood of the world's top private detectives led by a London based American called Craig Bradford. A German investigator, Kurt Neilson and the beautiful Contessa di Contini. Lew Grade informed Anderson that he had personally signed former Man From U.N.C.L.E. star Robert Vaughn in the lead. Anderson turned his attention to the second lead and signed actor Tony Anholt to play the part of Paul Buchet. Some weeks after the casting of Anholt, at a Screen Writers Guild dinner, Lew Grade introduced himself to the actress Nyree Dawn Porter, who had been a hit in the classic BBC series The Forsyte Saga. "I was sitting at my table when suddenly a cigar appeared over my shoulder followed by the legendary Lord Lew," remembered Dawn Porter. "He said to me, 'My dear, I'd like you to do a series for us.' With the shake of a hand the deal was done. Anderson was taken aback when Grade informed him that he had signed Dawn Porter, especially as the third character in the series had been written for a male. But Grade knew the importance of having a strong cast, especially when trying to sell a series internationally. Anderson relented and the part was rewritten for Dawn Porter.

The Protectors became Gerry Anderson's most successful TV series since Thunderbirds and a second season was quickly commissioned. The series theme tune, Avenues and Alleyways became a top forty hit for Tony Christie and until 2005 remained the singer’s longest-running chart hit.

Anderson was still under the impression that a second season of UFO would be commissioned, and the storyline was expanded to develop SHADO's Moonbase headquarters as a more major part of Earth's defence. Sylvia Anderson remembered that the new series would have fleshed out a feature of later episodes of UFO; the relationship between Ed Straker and Colonel Virginia Lake. "The main characters were, for the first time in a science fiction series, a couple." But when the second season was cancelled the Andersons decided to move the focal point of their new series to take place entirely on the moon.

Space: 1999 so impressed Lew Grade that he budgeted it at £3.5 million, making it, up to then, the most expensive British television series ever made.

Anderson's next task was to find a US actor with a suitably high profile to attract the American networks where it was vital the series succeed. However, Abe Mandell, the President of ITC in New York, had his own idea about casting. Mandell suggested the husband and wife team of Barbara Bain and Martin Landau who had been a big hit together on the US series Mission Impossible. Gerry Anderson agreed. Sylvia Anderson didn't: "I battled very hard and stood up to Lew Grade and said 'I don't think they're right. They were okay in Mission Impossible, but having seen them, I don't think we're going to get what we should get.' But he said that they were very popular in Mission Impossible, and that they were a good commercial bet and that was that." The casting wasn't the only disagreement that the Anderson's had behind the scenes during the creation and shooting of their latest venture and it soon became apparent that their marriage was falling apart. The first season of Space: 1999 took two years to complete and during this time tensions rose to breaking point.

The end of Space: 1999 signalled the end of more than one era for Gerry. It was 1976, Gerry and Sylvia Anderson were no more and neither was there any more backing from Lew Grade. Gerry Anderson's sixteen-year association with ATV was at an end, and for the first time he had to go it alone.

To say that I was a little surprised when Lady Penelope's pink Rolls-Royce was turned into a pink Ford is something of an understatement."

Suffering from a lack of confidence, with the only offer of work coming from a Swedish company who wanted him to make a promotional film for them, money started to run out and Anderson found himself living on the breadline. But in 1981 he was to see his fortunes take a turn for the better with a project that had its roots in a 1977 proposal.

Gerry Anderson and Reg Hill had been approached by the Japanese arm of ITC to create a new animated series for Japanese television. The series was entitled Thunderhawks but did, like so many other of Anderson's late 1970s projects, fall through before it got too far. But in 1981 he got the chance to make a revamped version of the proposed series entitled Scientific Rescue Team Techno/Voyager. It would later air in both the UK and the USA as Thunderbirds 2086. At the same time Anderson entered into a new business partnership with Christopher Burr who was able to secure financing for a new puppet series, Terrahawks. For the series, a new style of puppetry was introduced, a sophisticated form of glove puppetry which was dubbed Supermacromination.

In 1983 Gerry Anderson and Christopher Burr met with US TV executives in order to sell Terrahawks to North America. The series had not been an immediate success when it had initially aired in the UK but after a slow start it began to receive a very respectable audience of around 9 million viewers, and that was enough for London Weekend Television, together with Japan's Asahi Tsushin Advertising Agency and Anderburr Pictures (a company set up by Anderson and Burr) to finance a further 13 episodes on top of the original 26. Although changes in ITC's management meant that Gerry no longer had the backing of Lew Grade, he quite naturally thought that the show's healthy viewing figures combined with Anderson's own reputation would be enough to land a deal. However, this proved not to be the case.

Where Terrahawks failed, according to the US execs, was that the puppets were depicting human beings and US audiences preferred their puppets to be distinctly non-human. Out of this was born an idea for a show that would use human actors for the human roles and puppets for the alien ones. Gerry and Christopher decided to set the series on a space station crewed by both alien and human police officers and set round a precinct that had a distinct New York feel to it. It would be called Space Police. A 53-minute pilot was made but in spite of an initial interest by TVS, Anderson failed to raise the necessary finance and ultimately the series was dropped and consigned to the shelf.

Anderson went off and made another series called Dick Spanner using stop-motion animation as opposed to marionettes. However, the series which was based on Raymond Chandler's down-at-heel private eye character Philip Marlowe got a very limited showing on British TV although certainly enough to elevate it to 'cult' status. But Space Police wasn't finished yet. Eight years after the pilot had been made Anderson got an unexpected call from John Needham of Mentorn Films who was keen to develop new television programmes. Needham asked Anderson if he had any 'properties' that they might be interested in.

Needham managed to secure a commission from the BBC to develop a 13-part series on a budget of £750,000 per episode. The aliens would no longer be played by puppets but by actors wearing masks. Then, with production set to commence in early 1993 the BBC pulled out. Another problem that they came up with was that they could no longer use the original title of Space Police as it had been registered as a trademark in the US by toy manufacturers LEGO. Alternative titles were suggested such as Precinct 88 and Demeter City Blues before Space Precinct was finally decided on.

Space Precinct was one of the highest-budgeted shows Gerry Anderson ever produced, but the series had taken many years to come to the screen and even then it was beset with further problems. In spite of the BBC's pull-out funding was found from a company called Grove Television. But after going into full production the money began to dry up. Eventually enough money was found to complete the series and got its first UK showing on the satellite/cable channel Sky One airing at 700pm on Saturday 27 May 1995. Then, Sky had a much smaller audience than it has today but still backed it with a huge launch party and a press conference with a photo call for the national press. However, on terrestrial television it didn't get the best of deals.

The show aired on BBC2 and was given a 6pm broadcast slot. Anderson was not overly happy with this as the show was intended for a more adult audience and felt that it would have been better received had it been given a primetime showing. Furthermore, because of its early evening transmission the BBC ordered that scenes of explicit violence be completely removed from the show. In some cases certain scenes had to be re-shot to comply with the BBC's requests. The result of this was that many viewers only ever saw a watered down, sanitised version of the show.

There was one more Gerry Anderson produced series to be screened before the end of the 20th century, and that was Lavender Castle. Whilst working on Space Precinct Anderson was approached by the science fiction and fantasy artist Rodney Matthews, who showed him a collection of highly detailed and bizarre illustrations. Anderson told Matthews that he would like to create a new series based on the artists' drawings, but they needed to be developed further. Anderson eventually took the developed proposal to the BBC who promised to back a 26 episode series. However, soon after, the Corporation withdrew its backing without explanation, and Anderson was unable to get Carlton Television to back it. Craig Hemmings of Carrington Pictures International agreed to finance a full series which was made at Cosgrove Hall. The series, which consisted of 26 ten-minute episodes, was first broadcast on 7 January 1999 on the ITV Network as part of the 'Children's ITV' strand and became the first Gerry Anderson series to be fully networked since Four Feather Falls in 1960.

As the decade, and indeed the millennium came to a close, Carlton Television approached Anderson with a view to recreating some of his famous Supermarionation series of the 1960s for a 21st century audience. Aptly, the series chosen for testing purposes was the first to have originally gone out under the Century 21 banner Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons.

Having created Lavender Castle with CGI graphics it was quite evident that this was now the way forward in animation and there was never a chance that 'Scarlet' would be a puppet remake. With a 26-episode plan and a £22 million budget, the Indestructible Production Company was formed to produce the new series. New Captain Scarlet was the first Gerry Anderson series to be filmed in the 16:9 widescreen format and also the first to be made in HD. ITV announced that the series would premiere on its Saturday morning flagship show Ministry of Mayhem (MOM) in early 2005. Introduced by children's presenters Holly Willoughby and Stephen Mulhern, 'MOM' was very much in the style of the classic 1970s series TISWAS, featuring kids games, appearances by pop and TV personalities, much bucket-of-water throwing and a series of popular cartoon shows. The first episode to feature New Captain Scarlet was broadcast on 12 February 2005 and although it was quite obvious that this was a brand new and innovative series, many fans enthusiasm was dampened by the way in which the series was broadcast, being divided up into two segments with a ten minute breakaway in between featuring 'MOM' style games. Once again, poor programme planning by ITV seemed to have scuppered Gerry Anderson's chances of a successful comeback to prime-time viewing.

Round about this time, Anderson became (loosely) involved with a movie project that would bring Thunderbirds to the big screen again, only this time using real actors instead of puppets. However, as he never actually owned the rights to the series, he had no artistic control over the new Thunderbirds movie and was only employed as an advisor. It soon became apparent that Anderson was intensely dissatisfied with the project and he very soon distanced himself from it, refusing to even comment on it. In an interview with The Stage Anderson told their reporter, "I had absolutely nothing to do with it. Someone acquired the movie rights, and that was it. To say that I was a little surprised when Lady Penelope's pink Rolls-Royce was turned into a pink Ford is something of an understatement."

For Gerry Anderson, by now a sprightly 75, the New Captain Scarlet series came as a welcome relief to years of making puppet series. "I hated ruddy puppets. There was a ghastly thing on TV once called Muffin the Mule and I found it both crude and inept. All those strings and grimacing faces. It made me shudder - and almost physically sick. And Twizzle wasn't that much better, or our successor, Torchy, The Battery Boy - dreadful papier-mâché faces and fixed expression. The thing was - beggars can't be choosers." Like it or lump it, from the early days of Supermarionation Gerry Anderson had overseen many puppet worlds. In fact, to stress the marked difference between his old puppet series' and his latest CGI one he had to invent a new term: Hypermarionation.

In early 2010, Anderson was diagnosed with Alzheimer's Disease. However, it wasn't until June 2012 that he went public with the story for an Alzheimer's Society walk launch, to raise awareness of the illness. By now 83-years-old, Gerry Anderson said of living with the condition: "I've lost my freedom." Speaking on BBC Berkshire radio he said: "I don't think I realised at all. It was my wife Mary who began to notice that I would do something quite daft like putting the kettle in the sink and waiting for it to boil. Finally, I was persuaded to go and see the doctor and eventually I was confronted with the traditional test - a piece of paper with drawings on it, taking a pencil and copying them. I thought 'Why are they doing this? A child could do this'. But when I started to copy the drawings, that wasn't the case." Just six months later, on 26 December 2012 Gerry Anderson passed away.

Gerry Anderson created a world of children's characters that stand tall alongside the giants of the literary world. Like Alice, Snow White and Mary Poppins, Anderson's characters are simply timeless in their appeal. And in creating these characters he carved a unique place for himself in the heart and consciousness of the television watching public that spans the generations. The kids of the 1960s who grew up watching the thrilling adventures of International Rescue can only marvel as they watch their own children and grandchildren rediscover the magic of Thunderbirds (a new animated series Thunderbirds Are Go! began airing in 2015) and other Supermarionation series each time his productions are re-shown, which is quite often. And until his health worsened, even though he had been showing conditions of the symptoms up to ten years before, the man showed no signs of retiring. "That is just not anywhere in the plan," he said some years before. "The only way I'm going out, I always tell people, is when someone finally cuts the strings."

Published on May 16th, 2020. Written by Marc Saul for Television Heaven.