The Face of Evil

Reviewed by Daniel Tessier

1977 began with the return of Doctor Who after a short, mid-season hiatus. Tom Baker’s Fourth Doctor arrived back on the screen on New Year’s Day in Part One of The Face of Evil. What the Doctor had been up to on his Christmas break we do not know, having left Gallifrey at the end of The Deadly Assassin and travelled alone for who-knows-how-long. The second half of Doctor Who’s fourteenth season went on to include the popular serials The Robots of Death and The Talons of Weng-Chiang (although the latter has undergone a major re-evaluation by some modern critics). Among these well-remembered serials, The Face of Evil is sometimes overlooked, in spite of being one of the series’ most fascinating and inventive stories, and introducing one its most popular companions.

The series’ producer and script editor, Philip Hinchcliffe and Robert Holmes, had the difficult task of introducing a new sidekick after Elisabeth Sladen left the series after three years. Her character, Sarah Jane Smith, had become (and remains) one of the most beloved companions in Doctor Who’s long history. The introduction of a new companion was to be staggered to drive up interest. Following Sladen’s farewell in The Hand of Fear, the Doctor adventured alone in The Deadly Assassin, an opportunity to placate Baker’s growing ego as leading man. The plan was to have one-off sidekicks for the next two serials, with the final story of the season introducing the new regular co-star.

Hinchcliffe and Holmes conceived of a character who would be tougher and more proactive than previous assistants, and for whom the Doctor could act as a teacher. This potential companion would be a “primitive” or “savage,” who the Doctor would school in civilised society. The creatives envisaged someone who would combine elements of The Avengers’ ass-kicking Emma Peel and Eliza Doolittle from Shaw’s Pygmalion. Around the same time, up-and-coming screenwriter Chris Boucher submitted a proposal for a serial under the title The Mentor Conspiracy. His proposal included an intense and capable fighter called Leela – named for Leila Khaled, the Palestinian hijacker and PFLP member (not something that was widely publicised at the time, and would surely never be permitted by the BBC today).

Hinchcliffe and Holmes saw Leela as a clear match for their companion idea, but the decision to keep the character one wasn’t made until late in the day. While The Mentor Conspiracy was not picked up, Holmes was sufficiently impressed by it to commission another script, initially titled The Tower of Imelo, in which Boucher reused Leela. This script would evolve into The Face of Evil, with Boucher requested to write two potential endings: one in which Leela would stay on her own planet, and one in which she would leave with the Doctor.

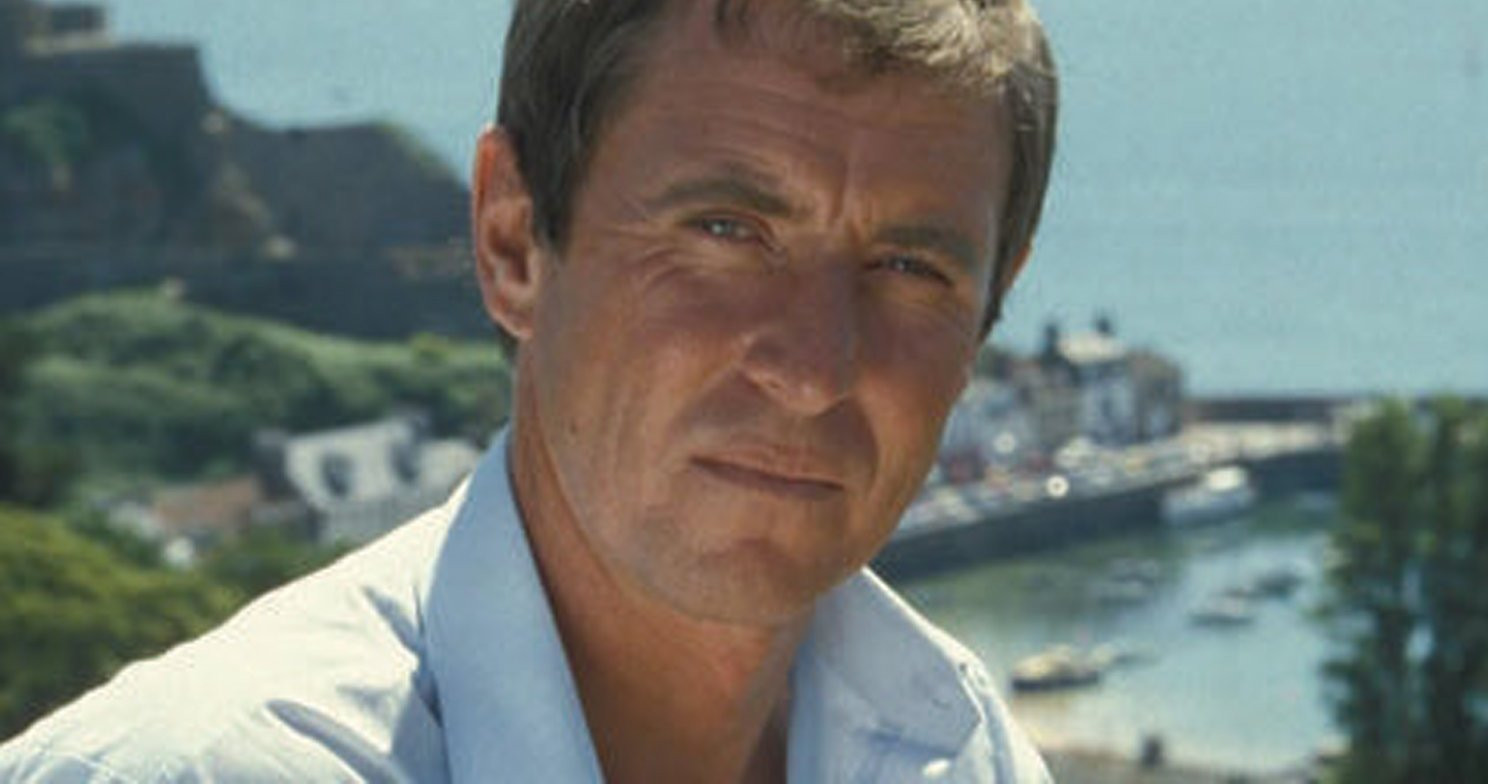

Over twenty actresses auditioned for the role, opposite The Face of Evil’s director, Pennant Roberts, standing in for Baker as the Doctor. A then little-known actress named Louise Jameson won the role; following the career-boost of co-starring in Doctor Who, she would go on to become a familiar face on British television, known for regular roles in The Omega Factor, Tenko, and Bergerac. Outside Doctor Who, Jameson is today best known to soap viewers, having played matriarch Rosa di Marco for two years on Eastenders, and is already almost three years into her role as Mary Goskirk on Emmerdale (which, under its earlier name of Emmerdale Farm, gave Jameson her first recurring TV role in 1973).

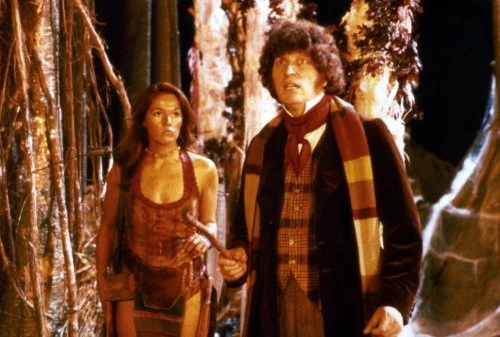

Jameson’s portrayal is fondly remembered by many due to her, for the time, rather revealing costume, a teatime-friendly attempt at Raquel Welch’s cavewoman outfit from One Million Years BC (and very tame by today’s standards). Popularly considered to be cast “for the dads” watching with their kids, Leela was far more sophisticated than this suggests. It’s easy to see why Jameson won the role. She plays Leela with a cautious but inquisitive nature, and while uneducated, it’s clear the character is highly intelligent. While Leela is violent – far more so than most hero characters on the series – her aggressive and uncompromising attitude is underpinned by a sweet, almost childlike sensibility. After extending the character’s stay until the end of the season, Jameson’s performance and the possibilities for the character meant that Leela was quickly granted a stay as the new, full-time companion, remaining until the end of the following season. However, Jameson didn’t have an easy time on the series to begin with, being forced to wear uncomfortable red contacts to turn her blue eyes brown, and frequently clashing with Baker, who was becoming increasingly unhappy about sharing the limelight.

The Face of Evil is the first of three serials that Boucher provided for the programme. Of Doctor Who’s many writers, Boucher had one of the best heads for science fiction, providing scripts based on fascinating conceits and exploring their consequences. The Face of Evil is perhaps the most intriguing of all. One of its several working titles, The Day God Went Mad, was perhaps too revealing, but also incredibly evocative, and it’s a pity it was ditched for the more standard, “Doctor Who-y” title.

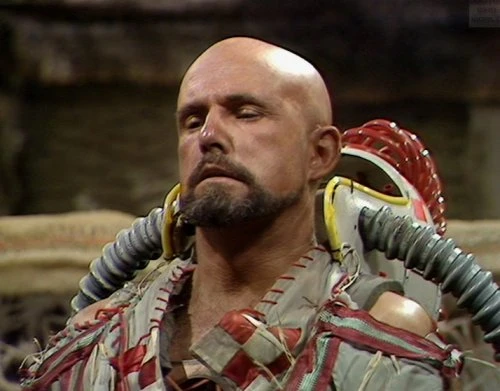

The Doctor arrives on a nameless planet in the distant future, quickly running into Leela, who has been kicked out of her tribe for questioning the existence of their god Xoanon. While she is healthily sceptical, she is still unnerved by the sight of the Doctor, whose face is that of the “Evil One,” a powerful being who supposedly keeps Xoanon prisoner beyond an impenetrable black wall. The Doctor rapidly becomes involved in the tribe’s internal politics, with both the shaman Neeva and upwardly mobile warrior Calib wanting to use him to strengthen their position. Calib and Neeva (Leslie Schofield and David Garfield, who had both appeared in Patrick Troughton’s final Doctor Who serial, The War Games) hold opposite positions regarding their tribal religion. Calib doesn’t believe any of it, but he’s smart enough to know not to rock the boat, and happy to use his captive Evil One to make a power move. Neeva, on the other hand, is a true believer, and is the only one who can communicate directly with Xoanon.

Things take a very interesting turn when we hear Neeva speaking to Xoanon, through a radio transceiver. The alleged god speaks with the Doctor’s own voice (Baker hamming it up nicely), dropping the cryptic statement, "At last we are here. At last I shall be free of us." The Doctor recognises the various relics and totems in the Neeva’s sanctuary as the equipment of a planetary expedition. The tribe of the Sevateem are descendants of the survey team, while their enemies behind the black wall, the Tesh, originated with the starship’s technicians. The first episode ends with a stunning cliffhanger, as Leela leads the Doctor to the entrance to the Evil One’s domain: a vast likeness of the Doctor’s face, carved into the side of a mountain.

While the inclusion of space colonists who have returned to savagery over hundreds or thousands of years wasn’t especially original, even in the 1970s, the addition of the Doctor somehow as both their god and devil adds a fascinating and unpredictable element. Equally intriguing is that the Doctor has no idea why his likeness might have been copied and doesn’t remember ever being on the planet before. (We might speculate that this belongs in his personal future, but this doesn’t seem to be the case, and when exactly the Doctor came to this planet remains a mystery.)

As the plot progresses, with the Doctor, Leela and the Sevateem entering the Tesh’s downed spacecraft, it’s quickly revealed that Xoanon is the ship’s computer. Mad computers are ten-a-penny in sci-fi, but Xoanon is an unusually fascinating example. It seems the Doctor had encountered the ship before and tried to fix the damaged AI by wiring it up to his own brain, but forgot to wipe his personality print from the data core. The result is a supercomputer with a catastrophic split personality complex, who has been manipulating the two strands of its crew in a eugenics experiment to act out its own internal struggle. The Sevateem were sent outside to become a physical, energetic race, while the Tesh were confined to the ship and bred to develop psychic powers.

Xoanon inhabits a central complex on the ship, into which the Doctor steps, finding himself surrounded by projected images of his own face. The third episode ends with an even more powerful cliffhanger, one of the most unsettling in the entire series. Confronted by the manifestation of his own madness, Xoanon finally cracks. Speaking in multiple voices, he breaks down, with the episode ending on Baker’s warped, digitised face as he shouts in a child’s voice: “Who am I? WHO AM I?” The effect is profoundly disquieting.

The child who provided the voice, Anthony Frieze, won a competition for a behind-the-scenes set visit. He was a pupil at the school at which the director’s wife worked; the chance to play a small role in the episode was an unexpected bonus. Aside from Baker, three other actors provided additional adult voices for Xoanon: Rob Edwards and Pamela Salem recorded their cameos while filming the following serial, The Robots of Death, while Roy Herrick would get a proper role the following season in The Invisible Enemy. Salem had caught the production team’s attention when she auditioned for Leela.

With the recent, controversial revelation that the Doctor has had countless lives lost in the mists of time, several fans have suggested that perhaps the voices used by Xoanon are all those of the Doctor, the unfamiliar ones having been dredged up from somewhere in his subconscious. The idea of the glamorous and posh Pamela Salem playing the Doctor is alone worth entertaining this idea for.

The Face of Evil boasts one of this period’s best scripts, with the clever central concept decorated with some wonderful dialogue, with the Doctor getting the choice cuts. Perhaps his best is “The very powerful and the very stupid have one thing in common: they don’t alter their views to fit the facts, they alter the facts to fit the views. Which can be uncomfortable if you happen to be one of the facts that needs altering.” A line which is, frustratingly, more pointedly relevant now than ever. Another lovely moment is down to Baker himself, who disapproved of a violent altercation between the Doctor and a warrior. He substituted a doom-laden threat to kill him with a “deadly jelly baby” in lieu of actual violence. (Just as good is his response when he’s dared to make good on his threat: “I don’t take orders from anyone.”)

The script is realised with some excellent practical and visual effects. Early plans to film the external scenes in a real forest were dropped, with a jungle set build in studio instead. It’s remarkably atmospheric, and the decision to record these scenes on film – visual shorthand at the time for location footage – adds to the effect, setting them apart from the videotaped interior scenes. There’s some great video effect work as well, particularly the gnashing phantoms that manifest in the forest when Xoanon defends against outside attack. Clearly influenced by the classic film Forbidden Planet and its “creatures from the id,” these entities are rendered as spectral outlines of the Doctor’s own furious face.

As ever, though, it’s not all successful. The Sevateem really are the most physically unimpressive bunch of tribal warriors ever committed to film, and the decision to add dark make-up to them is both questionable and ineffective (although earlier tests had Jameson virtually blacked up, so we must be grateful for small mercies). We’ve also got to wonder about the demographics on this planet: Leela is the only female member of the tribe we see clearly, and the Tesh are apparently all male. It’s hard to see how this society is going to survive even if Xoanon’s reign of terror is ended. The Horda, nasty little critters the tribe use as an execution method, are pretty rubbish too.

It wouldn’t be Doctor Who without a few embarrassing flaws, though, and they in no way detract from the impact of the story. This is intelligent, literary science fiction, something that the series only rarely tried. It’s an excellent introduction for both Louise Jameson as the new leading lady and Chris Boucher behind the scenes. Indeed, he’d impress even more with the very next serial.