The Fob Watch Approach to Doctor Who?: 'Warriors' Gate' and 'Castrovalva'

This article will examine the Doctor Who serial 'Castrovalva' (1982) in relation to 'Warriors' Gate' (1981). 'Castrovalva' was written by Christopher H. Bidmead while 'Warriors' Gate' was written by Steve Gallagher with considerable input by director Paul Joyce and script edited by Bidmead. There are parallels between the two serials whether or not Bidmead was consciously influenced by the former and wanted to extend the arc of Season 18 to the first serial of Season 19. This would be the Fob Watch approach where in new Who Russell T Davies took the idea of the fob watch from Paul Cornell's 'Human Nature'/'The Family of Blood' and used it in 'Utopia' (2007). The original script and novelisations of 'Warriors' Gate' and 'Castrovalva' will also be mined for what they can tell us about the similarities between the two serials.

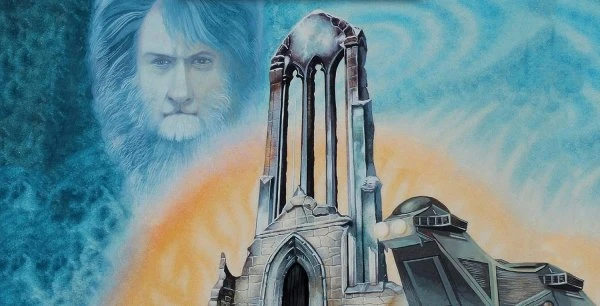

As its title suggests, the idea of gates is important in 'Warriors' Gate', whether that be the void (which stands at the intersection between E Space and N Space), the archway or the mirror. There are fantasy elements to this serial. The connections with Cocteau's La Belle et La Bete (1946) have long been noted (see Andy Lane, Martin Wiggins' DVD Production Notes, Billy Smart and Frank Collins). These include the visual portrayal of Biroc, the void, the archway taking the place of the enchanted castle, and seemingly inanimate figures that spring to life guarding the banqueting hall. The world behind the mirror of the Tharil palace and gardens is also presented in monochrome giving the feeling of a different reality.

The title of the serial 'Castrovalva' is similarly key literally meaning a fort with a hinged door and therefore involves crossing boundaries, both for the Doctor and his companions Nyssa and Tegan and for the television viewer. The boundary may at first appear to be one of entering fantasy but the locale turns out to be composed of hard science. Fantasy motifs from fairy tale and medieval Romance include the quest for Castrovalva, the visual presentation of the castle - creamy with flags raised - the healer figure (in this case Mergrave dressed in a soothing pink), the brightly coloured hunters, the feast, and a figure akin to the shape shifter. But the locale is held together by a web with the Master (the Portreeve) having used the Doctor's companion Adric's mathematical skill as a means of creation.

However, the more fairy tale/fantasy elements in 'Warriors' Gate' did not signify fabrication whereas in 'Castrovalva' the fairy tale like castle is held in balance by a web composed of hard science which is the 'reality' of that world. So there is a key difference between the two serials even though both feature thresholds with similar architectural walkways above the main room, although 'Castrovalva' was also inspired by the prints of M.C. Escher, and though both draw on hard science.

There is a door keeper, a porte reeve in 'Castrovalva' but this idea is already prepared for in 'Warriors' Gate'. In the earlier serial, the Tharil Biroc is a Time Sensitive who is forced to navigate for Captain Rorvik and his crew. Near the start of the serial, Biroc sees an image of the Doctor's TARDIS which appears on a screen in Captain Rorvik's control room and this is significant since the TARDIS appears on our television screens in the void by the archway. There is a focus on Biroc's eye seeing the TARDIS, on the notion of vision. Television and especially television science fiction is a gateway to other worlds, imaginatively pictured as in this case, and here Biroc is a cross between a gatekeeper and a television director, who navigates the Doctor's TARDIS to the gateway.

Indeed, in the 'Warriors' Gate' novelisation, the idea that Biroc has foreseen and is in control of the sequence of events is made explicit. The Doctor is a character in a story directed by Biroc - hence the later 'do nothing':

Biroc had managed to glimpse as a unity the events that would follow...When Biroc watched and did nothing, it was because he already knew what was ahead

(Lydecker 1982: 115).

Biroc wants the Doctor to stick to his place in the story but the Doctor can't stop trying to evade the limits of the script.

Biroc and Lazlo are furthermore gatekeepers respectively bringing the Doctor and Romana through the mirror. 'Warriors' Gate' draws on the myth of Orpheus. Cocteau's Orphee (1950) and its sequel Le Testament d'Orphee (1960) embellish the concept of travelling between different universes (see Andy Lane, Martin Wiggins’ Production Notes, and Frank Collins). As Frank Collins notes, Cocteau revises the myth where Orpheus travels to the Underworld to bring back his dead wife Eurydice but where she vanishes forever when he looks back at her. Instead, Orpheus journeys through a mirror into the Underworld where he must choose between Eurydice and a Princess with whom he has become obsessed (Collins 2019: 168-69). A tribunal returns Eurydice to life, however she suffers her fate when Orpheus looks at her reflection in a mirror. The mirror in 'Warriors' Gate' is also a threshold for those who are able to pass through. But for others all it does is reflect them.

In 'Castrovalva', the idea of doorways is also tied into the point that the world is a trap and the Doctor desperately seeks the 'way out'. Towards the end of part 3 the Doctor asks the Castrovalvans for the quickest way out and they all point in different directions meaning that the Doctor, Nyssa and Tegan are led 'round and round and back to the square'. It is towards the end of the serial that Adric, who created Castrovalva, can see the way out and leads the travellers to freedom. Similarly, in 'Warriors' Gate' the Doctor was trapped in E Space and he was ultimately able to cross to freedom.

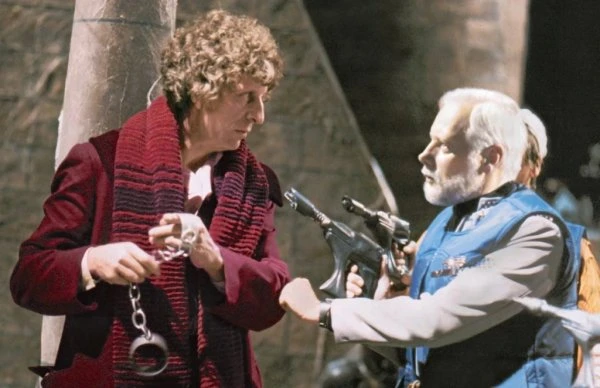

The Doctor is trapped in E Space just as the serial deals with slavery, of the human/oids to the Tharils in the past and of the Tharils in the present. The chain, made of dwarf star alloy, is a key image for holding the Tharils on Rorvik's ship. However, the Doctor is not in servitude to anyone. At the end of the serial, the captured Tharils from Rorvik's ship are all presented in a line passing through the gateways in a new type of chain and Romana's mission will be to assist Biroc in freeing Tharil slaves on other worlds. Just as the Tharils pass through the gateways to freedom so too does the Doctor to N Space.

Two spaces collapse in on themselves at the end of Parts 4. The Doctor’s antagonist also needs a way out - Rorvik is clear about this from the start and his actions are directed towards that aim. The Master doesn’t realise he needs a way out until right at the end when he is victim of his own trap. The creatures local to the spaces - Tharils and Castrovalvans - have powers that both the Doctor and the antagonist underestimate.

There’s a reference in the script and novelisation of ‘Warriors' Gate’ (but it was too difficult to render on screen) that the black and white world behind the mirrors was a realm where time was jumbled:

The Doctor is...keyed into a black-and-white still of a formal garden, Versailles style...There's nobody to be seen, but there are the sounds of a light-hearted garden party nearby, the two versions of reality jarring together.

(Gallagher 2024: 37)

Any attempt to get familiar with the gardens seemed inevitably to fail. There were broken-down fountains, resting areas with carved stone benches, groves of statuary...What (the Doctor) saw each time was the same place, the same objects, caught at a different stage of their deterioration. Any effort at making sense of the geographical relationships between these slices of time got him nowhere

(Lydecker 1982: 92)

Space is also jumbled in ‘Castrovalva’.

In this theme of collapse, in 'Warriors' Gate' Captain Rorvik prefigures the shard ovan. Rorvik uses his spacecraft to blast the mirror causing the physical manifestation of the gateway – the archway - to collapse into pieces when there is a back blast. However, Rorvik is an antagonist, who as we have seen is paralleled by the Master, whereas in 'Castrovalva' Shardovan is a protagonist who helps the Doctor by diving into the web on a chandelier and destroying the evil Master's fabricated world. Bidmead prefigures this incident in his novelisation of 'Castrovalva' where the castle first appears in a mirror in fragments:

A breeze shifted the alignment of the mirror at that moment, replacing the reflection of (Tegan's) face in the silver frame with a glimpse of a huge white hill that rose up beyond the tree behind her. It was not the hill itself that made her mouth drop open with surprise...But surmounting the...rocks ...was a neat townscape...in her excitement she brushed against the mirror, which tumbled from its perch and shattered unnoticed against the log. If she had turned to the mirror now she would have seen in it the image of the hill-top town broken into tiny fragments, a warning of the worst that was to come.

(Bidmead 1983: 57)

Later in the novelisation, there is an explicit reference to the Castrovalvan world being in shards, and more than just an image in a mirror:

The geography that had been...deceptive before was now blindingly baffling. A shifted mosaic of the Castrovalva they knew, fractured into tiny shards of space...This was not some confused picture, a viewer screen gone wrong, the image in a mirror pummelled into fragments - it was the very space they occupied

(Bidmead 1983: 114-15)

The image of the mirror is key. On the one hand, it is important since Castrovalva reflects on its own construction. But on the other hand, there are parallels between the mirror in 'Warriors' Gate' and the collapse of the Castrovalvan world. Just as the destruction of Castrovalva is prefigured in a broken mirror but is an inhabited space, the back blast in 'Warriors' Gate' destroys what is on one side of the mirror even though the area is not presented cracking in the mirror itself. Also unlike in 'Castrovalva' in the earlier serial a fantasy is not destroyed.

The notion of history also appeared in 'Warriors' Gate' and Castrovalva'. However, while a true history is presented in the former, the history of Castrovalva which led to this collapse is fabricated. In 'Warriors' Gate', the Doctor is given a vision of the past where the Tharils at the height of their empire ruled over human/oid slaves. With music playing, in the banqueting hall a female slave tended to the Tharils at dinner and was slapped in the process. In the case of 'Warriors' Gate' the point that civilisations fall is of importance since the Tharils become slaves to human/oids and their once great empire falls with the banqueting table now covered in cobwebs. Biroc at first endorses the Tharil imperialist empire (‘we are kings’) and its oppressive attitudes (‘they’re only people’) while coming to acknowledge that ‘we abused our power’. This truth seems part of the process of ending the cycle of master and slave that the Tharils and human/oids have been through before.

Meanwhile in 'Castrovalva', the Castrovalvans hunt for quarry in the wilds beyond the walls and feast on captured boar in their banqueting hall. This ritual is supposedly a mark to their ancestors who were a tribe of warring hunters but in fact this history is a fiction from beginning to end and Castrovalva is a creation of the evil Master's using the Doctor's companion Adric as a tool. Of the quarry, Ruther, one of the Castrovalvan hunters, declares that he has seen better to which Shardovan states that if they could cook Ruther's memories they would feast indeed. This introduces the theme of memory but it is not only Ruther's recollections of taking part in the hunt in the past which are key but so are memories of the Castrovalvan ancestors who never really existed in this fictional creation and so unlike in ‘Warriors’ Gate’ dissolution is brought by truth.

There’s an in-universe explanation for some linkage between ‘Castrovalva’ and previous serials – ‘Warriors' Gate’ and ‘Keeper of Traken’ (1981) included (the Castrovalvans talk in a similar Shakespearean way to the Trakenites). Adric’s memories and imagination are the origin of Castrovalva and he’s drawing on a limited palette of past experiences travelling with the Doctor such as the Castrovalvans feasting reflecting the banquet in ‘Warriors’ Gate’ and the peaceful simplicity of Castrovalva mirroring Traken.

The banqueting hall in ‘Warriors’ Gate’ is like Charles Dickens' Great Expectations (1860-61) where Miss Haversham's house becomes filled with cobwebs; in both that and ‘Warriors' Gate’ the setting becomes emblematic of characters states. But also, just as there are cobwebs in ‘Warriors’, as Martin Wiggins points out (1995: 10), in Bidmead’s novelisation of ‘Castrovalva’ stress is laid on the physical antiquity of the town, through, for example, dust on the tapestry. This is in addition to the dust in unused rooms in the Doctor’s TARDIS giving a sense of the old (Bidmead 1983: 17):

The Portreeve…brushed some speck from the tapestry producing a small cloud of dust

(Bidmead 1983: 81)

The olden quality of the books in the Castrovalvan library is also similarly stressed:

They came across a whole row of ancient dusty tomes entitled A Condensed Chronicle of Castrovalva

(Bidmead 1983: 83)

Mergrave returned with a trio of muscular Castrovalvan girls, each of whom carried a pile of dusty leather-bound volumes. It was the rest of the Condensed Chronicle.

(Bidmead 1983: 93)

The Master has indeed been waiting for centuries to spring his trap:

‘…I have contented myself with one small simple town, lying in ambush for five hundred years, waiting for this moment…’

(Bidmead 1983: 105).

So the notion of the past plays a vital role as in ‘Warriors’ Gate’, though in ‘Castrovalva’ there is the notion of the true past of the Master’s versus the falsified history.

'Warriors' Gate' and 'Castrovalva' both play with the common trope of menacing figures turning out to be friendly. The second episode of 'Warriors' Gate' ends with the POV of a creature (a Tharil) advancing on the Doctor's assistant Romana who is restrained and of it reaching its furry hand onto Romana's face whose scream leads into the end title music. Similarly, Castrovalvans observe the protagonists Nyssa and Tegan from behind a bush with menacing music playing. However, these figures turn out to be civilised beings beneath their hunting garb. 'Castrovalva' more strongly concerns the idea that appearances are deceptive from the hunters right down to the point that Castrovalva is a fiction which is ultimately brought crashing down.

'Warriors' Gate' features a humorous line about the Doctor's TARDIS being a box for midgets or a coffin for a very large man. In 'Castrovalva' the Zero Cabinet constructed out of the TARDIS's Zero Room looks unsettlingly like a coffin with the serial playing with the inversions of life and death. The Zero Cabinet is used to transport the Doctor to Castrovalva, seemingly a place of rest, but is carried to the Portreeve's house in what seems like a funeral procession. The truth of Castrovalva is, however, exposed and the Doctor is able to thwart the Master and return to the TARDIS fully recuperated.

So whether intended or not by Bidmead 'Castrovalva' displays connections, and modifications, to 'Warriors' Gate'. Frank Collins notes parallels between 'Warriors' and 'Logopolis' (1981) where, for instance, the fight against entropy and decay is intertwined with the delay of death as manifested by the nebulous Watcher, the transitioning figure between the fourth and fifth Doctors (2019: 172). The Watcher is in many ways the shadow of the Doctor's future that Biroc had earlier claimed to be. Furthermore, the theme of entropy is made evident in both through the prevalence of dust: there is dust everywhere in the banqueting hall and also as Logopolis crumbles. But the connections between 'Warriors' and 'Castrovalva' have until now remained largely unexplored and it is unsurprising to find these too. It is also worth concluding by pointing out that there are connections between ‘Warriors’ Gate’ and ‘Terminus’ (1983), also written by Gallagher, where there are slaves: the Vanir are slaves to ‘The Company’ and the Garm is a slave.

References

Doctor Who: Castrovalva by Christopher H. Bidmead (London: Target, 1983), The Black Archive #31 Warriors’ Gate by Frank Collins (Obverse Books, 2019), The Dream Time by Stephen Gallagher (Manchester: Cutaway Comics, 2024), ‘Mirror Image’ by Andy Lane in In Vision 50: Warriors’ Gate (Ed. Peter Anghelides and Justin Richards, 12-13), Doctor Who and Warriors’ Gate by John Lydecker [Stephen Gallagher] (London: Target, 1982), Doctor Who: Warriors’ Gate (1981), Jean Cocteau and the Realm of Videographic Fantasy by Billy Smart (Spaces of Television 6, 2013), ‘Paradoxical Paradise’ by Martin Wiggins in In Vision 55: Castrovalva (Ed. Anthony Brown, 1995, 9-10), Warriors’ Gate DVD Production Notes by Martin Wiggins

I'd like to thank Lewis Baston for making helpful suggestions for the writing of this article.

This article is dedicated to the memory of my good friend Matt Parsons (1974-2024) who tragically took his own life and to all those who have grieved for him. We love you Matt and will cherish the memories.