Covington Cross

1992 - United States‘the standard of the storytelling begins to improve in the last few episodes - sadly, the episodes that were never shown in America’

Covington Cross review by John Winterson Richards

While there really is no such thing as "so bad it's good," there is definitely a "so bad that it becomes mildly entertaining in small doses with just the right amount of beer."

A typical soapy American family drama set in an ignorant Hollywood writer's vague notion of Medieval England, Covington Cross seems at first a deliberate attempt to force its way into that category. Imagine John Hughes type teenagers, played as usual by older actors, complete with early Nineties hairstyles, running unrestrained around a version of Olde Englande that can exist only in the mind of someone who has never been to England or opened a history book. The cliches, anachronisms, inaccuracies, stereotypes, and plain bad dialogue, plotting, and pacing sometimes come across as intentional satire of the worst of Hollywood writing, and very funny satire at that - one is reminded of the brilliant MGM-style song and dance number about England in Harry Enfield's classic Sir Norbert Smith: A Life - except that in Covington Cross the writers and producers were apparently trying to be serious.

Even if it had been a joke, it would wear thin very quickly, so it is no surprise that the show was cancelled after thirteen episodes, only seven of which were actually aired on American network television, while only the pilot made it as far as broadcast in the UK. What is perhaps more of a surprise watching them all is that there is another reason why Covington Cross does not really make it into the "so bad that it becomes mildly entertaining" category: it is not entirely bad.

Indeed, some aspects are positively good. While the writing is distinctively American, the locations and most of the cast are British. The difference is illuminating. This is definitely not to say everything American is bad and everything British is good - too many exceptions on both sides could be cited to refute that, and indeed there have been times when the direct opposite might be argued - but Covington Cross is worth studying as an example of how a visible clash of cultures can doom a project from the start.

On a more positive note, it is also worth a mention on this website as an illustration of how first class professional actors who are determined to treat even the most unpromising material seriously can still deliver credible and compelling performances, and engage the viewer's interest in what might otherwise have been two dimensional caricatures of characters.

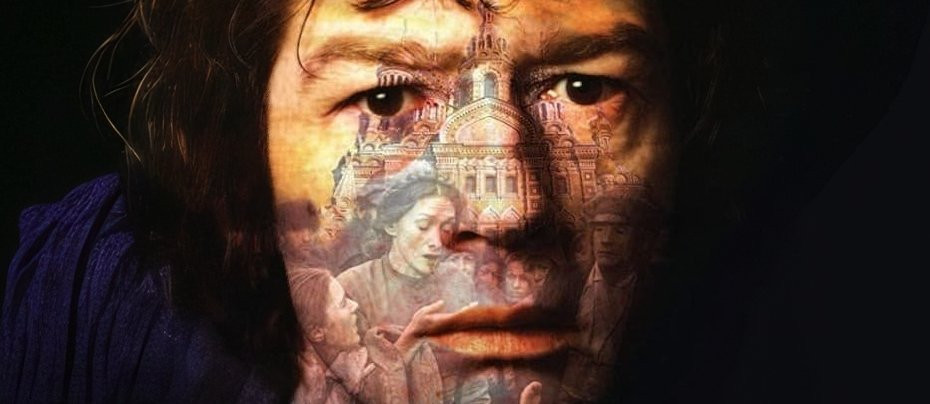

If nothing else, Covington Cross deserves to be loved for reuniting Arthur and Guenevere from Excalibur, Nigel Terry and Cherie Lunghi. Fans of the memorable 1981 film may recall Arthur expressing the hope that they might meet in another life, and here they do. It is interesting to note how Terry's career was defined by Medieval roles - his "breakthrough" was as John in the Oscar-laden The Lion in Winter, Arthur is the part for which he will most likely be remembered, and Covington Cross seemed to offer him the opportunity of serious American money at last. Sadly it was not to be, and he died relatively young and underappreciated. Here he gives us a likeable patriarch, sometimes a manly role model, sometimes a well meaning but confused father. His line delivery is frequently a thing of joy. "I have done this before, you know," he reassures his children as he rides off to a duel to the death with a much younger and stronger opponent. It is a genuine human moment in an otherwise farcical pilot episode.

Cherie Lunghi is lovely, as always, as the widow from the castle next door. Her character is presented as a capable businesswoman, which was probably intended as a modern touch, the irony being that the producers and writers probably never even heard of the Paston letters, and were therefore ignorant of the fact that she really did have her real life equivalent in the Middle Ages.

The always watchable James Faulkner, a versatile and subtle actor, here throws off all restraint and enjoys himself as a good old-fashioned snarling, sneering, scheming Wicked Baron with more than a hint of Basil Rathbone in the classic Errol Flynn version of The Adventures of Robin Hood.

Jonathan Firth, brother of Colin, plays Terry's son. Another son was played by Ben Porter in the pilot episode, but he seemed pretty undistinguishable from his brother, so he was sent off on Crusade for the rest of the show's run while another brother, the more distinctive Armus, played by Tim Killick, returns conveniently from the same Crusade. Two other siblings are played by non-British actors whose accents seem out of place, even if they are no less inaccurate historically than those of the British cast. Glenn Quinn, as the youngest son, who is being educated for a career in the Church for which he is particularly unsuited, is best remembered now for his later work in the first season of Angel and for the fact that he is another actor who died far too young. Ione Skye receives a surprisingly prominent place in the billing, indicative of her fairly high profile at the time as a young actress who was considered to have a big future ahead of her, but it never really happened. One sees why: although she is personable, she never really rises above the poor material she is given as some of her castmates manage to do.

Paul Brooke is well cast as the Friar who acts as Chaplain to the family: this is one of the few occasions in his long career where direct reference is made to his distinctive eye, which becomes a minor plot point in its own right. A truly distinguished guest cast includes Anthony Valentine, Julian Fellowes, James Nesbitt, Art Malik, Ian Hogg, David Calder, James Grout, Oliver Ford Davies, Sion Probert, John Cater, and even the future Dame Sian Phillips. Look out for Daniel Craig and Philip Glenister in early roles. Alex Kingston is the perfect tavern wench.

Although they were all were obviously just turning up for their cheques, they still did their jobs properly. So did most of the people in the production departments, even if their commitment to historical accuracy seems a little erratic. Given that the script has no such commitment at all, and indeed does not even give a clear date for the events - it could be set anywhere between 1280 and 1380, probably more towards the latter - it is to greatly the credit of those responsible for costumes, props, and set dressing that they made as much effort as they did. It is hardly their fault that the "authentic" castles used as locations are pierced by windows dating from a much later period, destroying all sense of these being dangerous times. A rousing score from Carl Davis confirms the impression that a lot of money was spent on the project, making it even more of a pity that a little of it was not diverted to paying someone who really knew what they were doing to fact check and edit the scripts properly. This is, of course, a frequent complaint.

In fairness, the standard of the storytelling begins to improve in the last few episodes - sadly, the episodes that were never shown in America. One even sees the very prestigious name of Herbert Wise (I, Claudius) among the directors of these later episodes. They are still very crude, but there are some good plot ideas and at least some of the characters begin to develop a bit. If the show had been given a little more time, it might have discovered the style and tone that was to work so well for similar pseudo-historical shows like Hercules: the Legendary Journeys and Xena: Warrior Princess only a few years later.

Alas, the eventual improvement was too little too late. The hilariously bad - but not hilarious enough or bad enough to stand out - opening episodes had already fixed the image of show as a sort of Beverly Hills 1350. As such it was not teen drama or historical drama, and so it appealed to fans of neither. It was - as misconceived as it was, at least in some respects, well made. The mainly British cast and crew deserved so much better from their American paymasters.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on July 5th, 2024. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.