Have I Got News For You

1990 - United KingdomReview: John Winterson Richards

Like so many great ideas, it was as simple as it is brilliant: combine a current affairs satire with a quiz show. Television controllers like current affairs satires because they are prestigious and, if they happen to touch the 'zeitgeist,' they can get big ratings in difficult time slots. However, they also dislike them because they are expensive to make, especially in the review or magazine format which requires scene changes every few minutes - situation comedies are cheaper because they stick more to the same, er, situation.

So television controllers also like quiz shows because they are cheap - very cheap. There is only a single set, itself reusable, and no shortage of members of the public, or perhaps slightly better known faces "between jobs" and frightened of being forgotten, willing to work for peanuts and the opportunity simply to be on television. This is why they pad out the schedules with them, not because they are necessarily popular - but when they are, the ratio of viewers to cost is greater than the most epic production.

It is therefore not difficult to imagine the scene when Jimmy Mulville's Hat Trick Productions pitched Have I Got News For You - let us stick to HIGNFY from now on - to the BBC. Any half talented director would have added choral music, a bright spotlight from above, and all the other tropes that indicate that someone has just seen the Holy Grail.

There are two teams, each of two people, which is as minimal as you can get. One team member is a guest of the week and the other a regular team captain on whom the director can rely to keep the talk going even if the guest turns out to be useless. The guests are usually journalists, politicians, or aspiring stand up comedians willing to turn up for incredibly little money in the hope that the exposure on the box will boost their careers.

Usually it does not - a dull person is revealed as a dull person - but when it does, it really does. Just ask Boris Johnson, who, contrary to the impression that he was almost a regular, appeared on it only seven times, four as host or chairman. It is fair to say that it did him no harm.

The basic format is that there are normally four rounds and a caption competition at the end if time permits. They usually involve spotting the relevance of a film or pictures to stories in the week's news, identifying the "odd one out" among four topical pictures, and filling in the missing words of headlines. Sometimes the format is altered as a tribute to a guest, as when Bruce Forsyth was guest chairman and a round based on his popular quiz Play Your Cards Right satirised the Americans putting wanted Iraqi leaders on a deck of cards. In general, little expenditure is required in terms of technology or props. Notice the constant theme here.

To be honest, the competitive element in HIGNFY is about as real as it is in professional wrestling. The quiz is just an excuse for witty banter about the week's news stories. Little of this is spontaneous: HIGNFY employs a strong team of scriptwriters. Yet, as with professional wrestling, a lot of effort is still required and there remains an element of risk. Some of the most memorable moments occur when participants, who include some very clever people, really go off the cuff - and sometimes totally off piste. Appearances by Paula Yates and Piers Morgan are compelling in a horrible, watching-a-car-crash-and-cannot-stop-looking sort of way.

There are also occasions when one expects someone to be totally out of their depth only to come away with an increased admiration. Joan Collins' magisterial performance sticks in the mind.

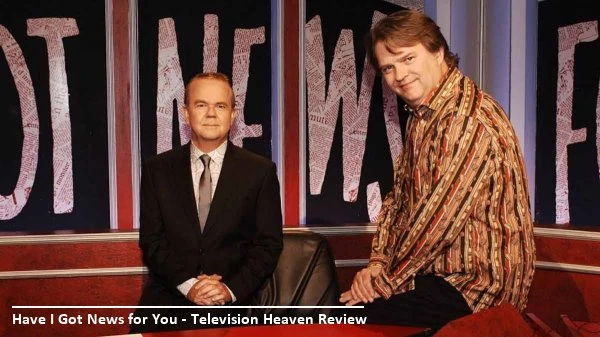

If truth be told, HIGNFY did not get off to a particularly good start. It got better, and grew in reputation, as the two regular captains grew in experience and confidence. The ability to spot potential talent has always been a particular strength of Hat Trick Productions, and their selection of two men who have served for thirty years, in one case without missing an episode, is further proof of this.

Ian Hislop was a relatively obvious choice. The nearest thing Britain has to the French notion of a "public intellectual," he was only a baby, or at least looked like one and was not so far away from being one, when he was appointed as Richard Ingrams' successor as Editor of 'Private Eye.' Since then, he is said to have become the most sued man in British legal history. He is quick witted, well read, closely plugged into current events, and not particularly modest about who knows it.

The selection of Paul Merton was more counterintuitive. A respected but not mega-successful stand-up comedian, he made his reputation with some dazzling improvisational skills on Whose Line Is It Anyway, another Hat Trick project. A carefully cultivated air of vagueness covers an extraordinarily fast mind. He is also very literate in the history and theory of comedy.

Together they have developed a formidable dynamic. Hislop is the expert who often acts as the "straight man" to Merton the performer. Although they work well together, there is often a real edge to their rivalry. This is not the gentlemanly competition of Frank Muir and Patrick Campbell or Arthur Marshall in Call My Bluff.

Yet if there was one casting decision that really made HIGNFY it was that of Angus Deayton as the chairman or host of the quiz. An obviously intelligent man with an authoritative, slightly supercilious manner and a touch of the young Peter Cook about him, he dominated the show and to a great extent carried it in its early years when it was finding its groove. Indeed, it comes as a surprise to realise that he was very much in charge of it for no less than twelve years - far longer than most shows last in total.

There was therefore serious doubt about whether the show could continue after he was sacked, ostensibly on moral grounds, in 2002. The fact he that was not replaced and that his role was filled by a series of guest hosts who changed weekly - a temporary measure, we were told, while they sought a permanent chairman - encouraged speculation that they were keeping his job open for him to return at some point after a suitable period of penance.

After all, it seemed strange that the BBC, a famously louche organisation, should suddenly discover that it could fire people for moral offences. While it would be a gross exaggeration to suggest that everyone in television is sniffing cocaine and having promiscuous sex, such things are considered so normal as to excite little comment. If the Deayton Standard was applied consistently, most broadcasters would suddenly find considerable gaps in both their talent rosters and their management structures. There was a strong scent of hypocrisy in the air.

Even stranger was the reaction, or lack of reaction, from his colleagues. Hislop is a tireless campaigner for justice as he sees it. While Merton is less small-p political, arguably his finest hour is a passionate and forensic dissection of the similar hypocrisy that ended to career of silent movie comedy star Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle (a documentary well worth watching in its own right, by the way). Given that polls suggested that the audience wanted to keep Deayton, Hislop and Merton could easily have got him reinstated if they had worked together to that end.

The truth seems to have been that practically everyone in the production already wanted Deayton gone for other reasons, and that his involvement with Class A narcotics and prostitution simply provided a convenient pretext. The display of on screen irritability between Deayton and his captains was not entirely an act. More importantly, Deayton's salary, reportedly £50,000 an episode and far more than the captains,' was the single largest item in the show's production budget. We return to a familiar theme.

The quest for a permanent replacement was apparently genuine, if short lived. Some interesting names were mentioned and some seem to be "auditioning" as guest hosts. However, there was a reluctance on the part of the best qualified people because of the feeling that Deayton had been treated shabbily - Stephen Fry, greatly to his credit, vowed never to appear on the show again. Meanwhile, the "temporary measure" of the constantly changing guest hosts was proving a great success. If some hosts were weak, the captains had by this point developed sufficient expertise to be able to carry an episode on their own if required, and audiences were intrigued when they saw different names advertised. In the end it was no great surprise when it was announced that the "temporary measure" would become permanent.

Since then, an episode has usually stood or fallen on the strength of the guest host. By far the most memorable, and, according to the viewers' ratings on IMDb, the most popular, is Brian Blessed's legendary first appearance in 2008, in which he goes totally Brian Blessed. Incidentally, at the time of writing, the second, third, and fourth places on the IMDb list are all held by episodes chaired by the same guest host, one Boris Johnson.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on June 10th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.