Hawking

2004 - United KingdomStephen Hawking’s life is one of those rare stories that seems almost purpose-built for drama: dazzling intellect, cruel physical limitation, youthful defiance and world-changing ideas. It is the sort of narrative that could easily tip into mawkishness or bombast in the wrong hands, which makes it something of a minor miracle that the BBC2 drama Hawking manages to be both stirring and, for the most part, restrained. Shown as a ninety-minute film, it revisits the early 1960s, when a 21-year-old Hawking arrived at Cambridge to begin his PhD, unaware that his greatest intellectual breakthroughs would coincide with the most devastating diagnosis imaginable.

From the outset, the drama positions itself not as a sweeping cradle-to-grave biography but as a focused study of a formative period. By narrowing its attention to Hawking’s early academic life and the emergence of his ideas about the origins of the universe, the programme avoids the temptation to summarise a lifetime of achievement and instead concentrates on the moment when possibility and fragility collide. Hawking is young, awkward, supremely confident in his intellect and only just beginning to imagine what he might contribute to physics. That sense of promise is brutally undercut when he collapses at a party and later learns that he has motor neurone disease, with doctors giving him, at best, two years to live.

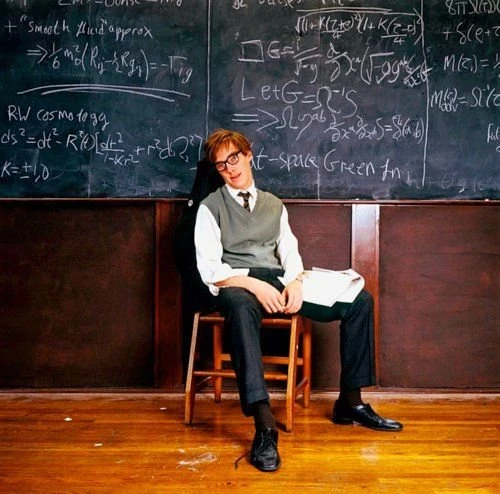

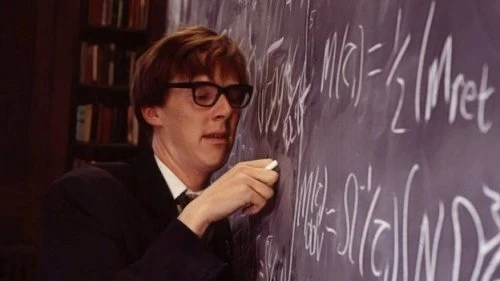

Benedict Cumberbatch’s performance sits at the heart of the drama and is the principal reason it works as well as it does. This was one of his early standout roles, before he became a familiar face on British television and in cinema, and it is remarkable how fully formed his portrayal feels. He captures not only Hawking’s physical decline but also his temperament: the impatience, the sharp humour, the refusal to suffer fools gladly. There is an ornery streak here that feels entirely convincing and oddly endearing. Anyone who celebrates his 21st birthday by putting Wagner on the record player is clearly not built to blend quietly into the background, and Cumberbatch makes that quality central to his interpretation.

The physical transformation is handled with care and subtlety. Rather than relying on grand gestures, Cumberbatch allows Hawking’s illness to creep in gradually: a stumble here, a slurred word there, the increasing difficulty of writing equations on a blackboard. These moments are never sensationalised. Instead, they are woven into the texture of everyday academic life, reinforcing the sense that Hawking is being forced to adapt even as his peers throw themselves into college routines, debates and late-night conversations. His world is shrinking physically just as it is expanding intellectually.

Hawking’s diagnosis initially paralyses him emotionally as much as physically. Unable to find a subject for his PhD and resistant to the well-meaning support of his supervisor, Dennis Sciama (John Sessions), he sinks into depression. The sense of stasis is palpable. While others race ahead, Stephen feels as though time itself has stalled. It is in these quieter stretches that the drama conveys something profound about illness: not simply pain, but the suspension of future plans and ambitions.

Jane Wilde (Lisa Dillon), whom Hawking meets at his birthday party, becomes a crucial anchor during this period. Their relationship is portrayed with warmth and sincerity, avoiding the easy sentimentality that often accompanies such stories. Jane is intrigued by Stephen’s talk of stars and cosmology, but she is not blinded by it. She recognises both his brilliance and his vulnerability, and her faith in him becomes one of the few things that prevents him from giving up entirely. When Stephen eventually asks her to marry him, it feels less like a romantic flourish and more like an act of defiance: a declaration that he intends to live, think and love on his own terms, regardless of medical predictions.

Intellectually, the drama plunges viewers into one of the most contentious debates in mid-20th-century cosmology: the battle between Steady State theory and the idea that the universe had a beginning. At the time, Steady State dominated, championed by the formidable Fred Hoyle, a blunt-speaking Yorkshireman and early science broadcaster. According to this view, the universe had always existed and always would. The notion of a beginning was, in some quarters, regarded as unscientific or even faintly theological. Hawking’s scepticism towards Steady State is portrayed as instinctive rather than dogmatic, a nagging sense that something about it does not quite add up.

One of the drama’s most effective scenes sees Hawking obtaining an early glimpse of a paper Hoyle is about to present at the Royal Society. Working through the calculations overnight, he identifies a flaw and publicly confronts Hoyle (Peter Firth) after the lecture. This moment could easily have been played as a swaggering triumph, but instead it feels tentative and risky. Hawking is not yet a giant of the field; he is a sick graduate student challenging an established authority. The confrontation causes a stir in the department, but more importantly it ignites Hawking’s confidence. For the first time since his diagnosis, he has proof that his mind remains as sharp as ever.

Another turning point comes with the introduction of Roger Penrose (Tom Ward), whose work on topology offers Hawking a new way of thinking. Topology’s emphasis on shapes rather than equations proves invaluable to someone who is beginning to struggle physically with writing. Penrose’s fascination with the fate of dying stars leads him to the concept of black holes and, crucially, singularities: points of infinite density where the known laws of physics break down. These ideas open a door for Hawking. If collapsing stars end in singularities, might the universe itself have begun in one?

The drama conveys these complex ideas with surprising clarity, given the constraints of a television format. While it inevitably simplifies some of the mathematics, it succeeds in communicating the excitement of discovery: the sense that familiar assumptions are being overturned. One particularly memorable sequence shows Hawking scrawling equations on a blackboard throughout the night, searching for the flaw in Hoyle’s argument. This kind of scene is a familiar cliché in films about genius, yet here it carries genuine emotional weight. It is not simply about intellectual victory, but about reclaiming purpose in the face of mortality.

Perhaps the most joyous moment in the drama comes at a railway station, when Hawking experiences a sudden Eureka moment. The huge grin on his face as he realises that Penrose’s mathematics can be run backwards — that instead of something collapsing into nothingness, nothingness might explode into something — is infectious. In that instant, the idea of the Big Bang crystallises not as an abstract theory but as a profoundly human insight, born of curiosity and persistence. It is a reminder that even the most abstract science is driven by moments of intuition and delight.

Not everything in Hawking is equally convincing. Some scenes veer towards the awkward or implausible, most notably one in which Stephen attempts to charm a glamorous blonde in a bar by explaining relativity. While it is possible that such an encounter occurred, it feels oddly out of place here, striking a false note in an otherwise grounded portrayal. There is also the curious issue of the dialogue, which at times feels disjointed and unnatural. Exchanges can jump abruptly, as though lines have been trimmed too aggressively or stitched together without sufficient smoothing. These moments are distracting, though rarely enough to derail the drama entirely.

Structurally, the programme is enriched by a secondary, interwoven storyline set years later. In 1978, American scientists Arno Allan Penzias and Robert Woodrow Wilson (Michael Brandon and Tom Hodgkins) are interviewed in a Stockholm hotel room on the eve of receiving the Nobel Prize for Physics. Their discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation — the faint afterglow of the universe’s earliest moments — provided the physical evidence that supported Hawking’s theoretical work. This parallel narrative serves as a quiet reminder that scientific breakthroughs are often collaborative across time and continents, even when the participants are unaware of one another.

The contrast between Hawking’s lonely intellectual struggle in 1960s Cambridge and Penzias and Wilson’s eventual recognition underscores the long arc of scientific progress. Ideas can be ridiculed or ignored for years before evidence catches up. When the American scientists describe how they detected an inexplicable radio signal from space, only gradually realising its significance, the drama gently reinforces the legitimacy of Hawking’s once-controversial conclusions. It is a satisfying structural device, linking theory and observation, youth and maturity, doubt and confirmation.

The supporting cast contributes solidly to the overall effect. Peter Firth brings authority and restraint to Dennis Sciama, a supervisor who is sceptical yet fundamentally supportive, allowing Hawking the space to develop his ideas without imposing his own. Other familiar faces populate the academic world convincingly, lending it texture and credibility. Murray Gold’s score, meanwhile, avoids melodrama, instead underscoring key moments with a light but emotionally resonant touch.

Hawking occupies an interesting place in the cultural representation of Stephen Hawking. A decade later, his life would be retold in The Theory of Everything, with Eddie Redmayne’s Oscar-winning performance and a broader focus on Hawking’s marriage and later career. That film, released in 2014 in the USA (2015 in the UK), reached a far larger international audience and enjoyed considerable commercial success. Yet there is something to be said for the BBC drama’s narrower lens. By confining itself largely to Hawking’s student years and early breakthroughs, it captures the rawness of a mind on the brink of discovery, before fame and public adulation set in.

Ultimately, Hawking is heroic without being triumphalist. It does not pretend that intellectual brilliance erases suffering, nor does it suggest that personal determination can magically overcome physical decline. Instead, it presents a more nuanced, and arguably more inspiring, message: that meaning and achievement can coexist with limitation, and that the life of the mind can flourish even as the body falters. Its flaws — those few clumsy scenes, some uneven dialogue — are real, but they are outweighed by the power of its central performance and the elegance with which it dramatizes ideas that changed our understanding of the universe.

Verdict ★★★★☆:

For all its imperfections, this remains a compelling piece of television: thoughtful, moving and unafraid to take its audience seriously. In telling the story of a young man racing against time, both personal and cosmic, Hawking reminds us that the greatest discoveries often emerge from moments of doubt, vulnerability and stubborn curiosity. It is well worth the ninety minutes it asks of us.

Support for Motor Neurone Disease can be found in the UK @ MND Association

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on February 5th, 2026. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.