Jackanory

1965 - United KingdomStorytelling had been introduced into children’s television from the earliest days of broadcasting when author, lecturer and broadcaster Paul Leysacc read tales from Hans Christian Anderson as part of the series For The Children (1937-39 and 1946-50). Later still, Johnny Morris had his own segment in Playbox, where he appeared as The Hot Chestnut Man, standing by a barrow of roasting chestnuts as he related his own self-penned stories. But by far the most popular and enduring storytelling series of all was the BBC’s wonderful Jackanory, although throughout its history it was not without its critics.

Although by the early 1960s the simple premise of a presenter reading straight to camera was still an integral part of series such as Play School, there had never been a series totally dedicated to storytelling, the point of view being that this was more suited to the radio series format in broadcasts such as "Children’s Hour" which had been telling children’s stories for many years. But in 1965, BBC2 Chief of Programmes, Michael Peacock informed producer Joy Whitby that there was a spare 15-minute teatime slot to be filled and he suggested stories. Whitby asked Anna Home and Molly Cox, who had been heavily involved in the storytelling element of Play School to come up with a format. In her book, Box of Delight's, Anna Home remembers: "It was agreed that the series would include all kinds of stories from traditional folk tales to Greek myths and legends and readings from well-known books." The look of the programme was ‘minimalist’, the storyteller having nothing more to sit on than a plain bench with perhaps a table or crate next to him or her with an object from the story sitting atop it.

To introduce the show the designers utilised the opening of an earlier children’s series, Picture Book, which began with a kaleidoscope image. The biggest problem that Home and Cox had was thinking up a title. "The team wanted to avoid the standard ‘story book’, ‘story time’ idea, but no one could think of anything better." Wrote Home. "Time was getting short when Molly Cox and I went for a holiday in Scotland and, sitting by the fire in a remote cottage, suddenly remembered a nursery rhyme that had something to do with stories."

The nursery rhyme they remembered went like this:

I’ll tell you a story of Jackanory

And now my story’s begun,

I’ll tell you another of Jack and his brother

And now my story’s done.

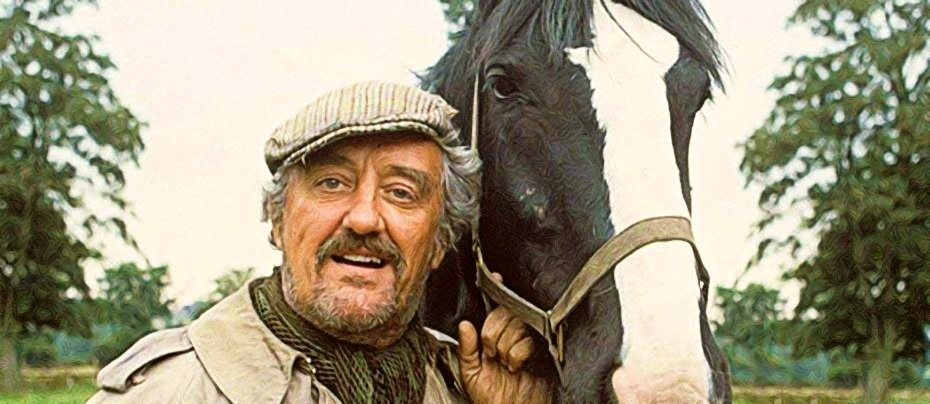

Jackanory debuted on Monday 13 December 1965 - the first story "Cap of Rushes" was told by Lee Montague, who read whilst seated on a white wrought-iron bench next to which stood a table -on top of which stood a jar of bulrushes. Initially, there was some criticism that the series would discourage reading among young viewers, allowing them to ‘opt out’ of picking up a book and reading something for themselves. Home acknowledges that when the series first aired the novelty of it may certainly have displaced children’s book sales. However, after a time this trend was reversed and Jackanory was seen as an encouragement in steering children towards books. "The producers believed that if children listened to stories being read their awareness to literature would be raised", she wrote. At first it was difficult for the producers to find storytellers who wanted to take part in the show. No one was interested. But soon the series began to attract stars from stage and screen and during its 31-year run over 400 storytellers read more than 700 tales. Among those esteemed stars were Margaret Rutherford, Dame Wendy Hiller, James Roberston Justice, Geraldine McEwan, Joyce Grenfell, Dame Judi Dench, Billie Whitelaw, Spike Milligan, Jeremy Irons, Ian McKellen and Prince Charles, who in 1984 read his own story, 'The Old Man of Lochnagar.' By far the most prolific Jackanory readers were Kenneth Williams with 69 appearances and Bernard Cribbins with 111. Alan Bennett read the last Jackanory "The House At Pooh Corner". Many children’s favourites were read more than once including Roald Dahl’s "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory", which was voted the viewers favourite in a 20th anniversary poll.

"Most Jackanory storytellers used outocue", wrote Anna Home. "Some purists felt this was a kind of cheat -not real storytelling. However, fourteen minutes of text is a lot to hold in the mind -and two programmes were often recorded in one session. But some readers could not use autocue or did not wish to. Wendy Hiller, who read Alison Uttley’s ‘Little Grey Rabbit’ stories in the second week of Jackanory was too short sighted to see autocue. She had the script typed on jumbo type and stuck into a false book." Some presenters and even some stories have proved to be controversial. In particular Rik Mayall's anarchic reading of Roald Dahl's anti-adult 'George's Marvellous Medicine' - a story about a young boy’s attempts to get rid of his granny, caused a storm of mail to the BBC with viewers claiming both story and presentation to be both dangerous and offensive.

As the series progressed it’s style went through a number of changes. Firstly illustrations were introduced. These were supplied by the likes of Quentin Blake, Gareth Floyd and Barry Wilkinson. Later filmed inserts were included and later still Jackanory Playhouse, a series of largely studio-bound plays based on traditional folk tales (BBC, 1972-85) spun-off from the original programme, but rarely used original scripts -with the exception of Helen Cresswell’s "Lizzie Dripping" (which was later remade as a series in its own right). By that time Anna Home had moved on, frustrated with budgetary constraints preventing the Children's Department from making live action drama. She turned director and eventually paved the way for the return of home grown drama serials on BBC Children's television. Looking to start a contemporary school drama in 1976, she was approached by Phil Redmond -and two years later was able to present another long-running TV series, Grange Hill. She has since received a BAFTA lifetime achievement award and, in 1993, an OBE. She is currently chief executive for the Children's Film and Television Foundation, helping to develop outside scripts for children's films and television.

The Jackanory format was one of the great survivors of early television. It was relatively cheap to make and regularly maintained a healthy audience of around 3 million viewers. That it is no longer a part of today’s television schedule is not only to the detriment of children’s television, but also to children’s fiction in general. Simple yet effective -Jackanory, one of the most popular children’s programmes of all time, more than deserves its place in Television Heaven.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on December 24th, 2018. Written by Laurence Marcus (14 October 2004) with thanks to Anna Home for giving permission to use passages from her book "Into The Box of Delights" published in 1993 by BBC Books. for Television Heaven.